by Bruce Cherney (part 1)

Two species that once numbered in the billions and had been common in Manitoba were driven to extinction in North America through human intervention.

One was the Rocky Mountain locust, which was the scourge of western farmers on both sides of the international border for its ability to lay waste to entire fields of crops. Manitoba naturalist Norman Criddle documented that the last two living specimens of Melanoplus spretus, the Rocky Mountain locust, were collected near Brandon, Manitoba, in 1902.

The demise of the locust was the result of both intentional and unintentional human activity.

Jeffrey A. Lockwood in his article, The Death of the Super Hopper (High Country News, February 3, 2003), wrote: “By converting these valleys (in Montana and Wyoming where the locusts resided until their population exploded and they spread outward in the billions) into farms — diverting streams for irrigation, allowing cattle and sheep to graze in riparian areas, and eliminating beavers and their troublesome dams (causing overland flooding, killing eggs and young) — the pioneers unknowingly wiped out locust sanctuaries.”

The most damaging blow, according to Lockhart, was the plowing up of the locusts’ home breeding grounds along the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains, which exposed “hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of these egg masses.” In the aftermath of turning over the soil, eggs littered farm fields, exposing them to lethal weather elements and the damaging rays of the sun, which effectively prevented them from hatching into another generation of ravenous locusts.

Since the advent of agriculture some 11,000 years ago, it has been the only insect species ever driven to extinction by humans.

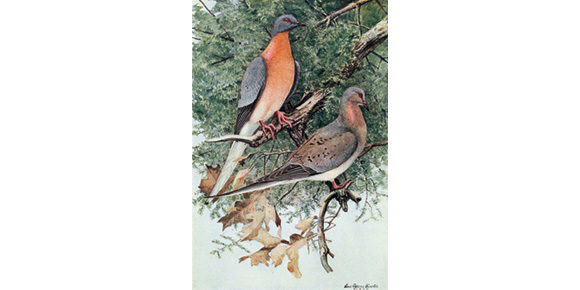

The other species to join the Rocky Mountain locust in the extinction ledger book was the passenger pigeon, Ectopistes migratorius, a bird which flew in flocks that were once so numerous that their passing overhead blotted out the sun from observers on the ground.

Ironically, the flightless dodo bird, once native to the island of Mauritius, but now also extinct, was actually an oversized pigeon.

In a post mortem study of the passing of the passenger pigeon, A.W. Schorger wrote in 1955 that no “other species of bird, to the best of our knowledge, ever approached the passenger pigeon in numbers.” He estimated that when Europeans began to settle North America that the species numbered between three and five billion pigeons, “that is an amazing 25 to 40 per cent” of the entire continent’s bird population.

In its heyday, the passenger pigeon was also the most numerous single bird species in the world.

In 1813, John James Audubon, the American naturalist, saw a flock of passenger pigeons moving at 60 mph and obliterating the noon-day sun. He said it took three days for the entire flock to pass.

In 1811, Alexander Wilson, another American naturalist, estimated that one huge flock, passing between Kentucky and Indiana, was 240 miles long and over a mile wide. “From right to left, as far as the eye could reach, the breadth of this vast flock extended,” wrote Wilson in his seven-volume work, American Ornithology, “seeming everywhere equally crowded. Curious to note how long this flight would continue, I took out my watch, and sat down to observe them. It was then half-past one, and I sat for more than an hour, but instead of diminishing, this prodigious procession seemed rather to increase both in numbers and rapidity, and anxious to reach Frankfort (Kentucky) before night, I rose and went on.”

By four in the afternoon, Wilson was in Frankfort and the stream of birds still had not diminished.

Later, Wilson attempted to calculate the number of passenger pigeons in this immense flock. Using three pigeons per square yard and the extent of the flock, he came up with a figure of 2,230,272,000 pigeons, “an inconceivable multitude, but probably far below the actual numbers.”

With such numbers overhead, it’s little wonder that people of the time period viewed the flocks with both marvel and as the harbinger of a coming apocalypse of Biblical proportion.

A flight over Columbus, Ohio, was recounted by an eyewitness in 1855: “As the watchers stared, the hum increased to a mighty throbbing. Now everyone was out of the houses and stores, looking apprehensively at the growing cloud, which was blotting out the rays of the sun. Children screamed and ran for home. Women gathered their long skirts and hurried for the shelter of stores. Horses bolted. A few mumbled frightened words about the approach of the millennium, and several dropped to their knees and prayed.”

(Next week: part 2)