by Bruce Cherney (part 3)

The key aspect of the reports about passenger pigeons migrating to Manitoba and elsewhere was the mention of them roosting in oak trees and “an arboreous situation.”

Passenger pigeons primarily fed on beechnuts, oak acorns and chestnuts found on the forest floor. But when such food was unavailable, and depending upon the season, they also fed on berries and softer fruits, such as blueberries, and cherries. They also ate earthworms, caterpillars and snails, particularly while breeding. Additionally, the passenger pigeon took advantage of cultivated grains, particularly buckwheat, when it found them. The species was particularly fond of salt, which it ingested either from brackish springs or salty soil.

It was their taste for cultivated grain that led individuals such as John McKenney to use such bait for their traps in the 1860s. At the same time, farmers viewed them with scorn as a descending flock could denude a field of its crop. It was their propensity to feed on grains that earned them the label of pests, similar to grasshoppers, by farmers, who willing added their strength to the firing lines that shot the birds in vast numbers.

To keep the birds from feasting upon settlers’ crops, Baron de Lahontan, a soldier stationed in New France (Quebec), who explored North America, wrote in September 1686 that the colonists declared “War against the Turtle-Doves (passenger pigeons), which are so numerous in Canada, that the Bishop has been forc’d to excommunicate ’em oftner than once, upon the account of the Damage they do to the Product of the Earth, With that view, we imbarqued and made towards a meadow in the neighbourhood of which, the Trees were cover’d with that sort of Fowl, more than with Leaves: For just then ’twas the season in which they retire from the North Countries, and repair to the Southern Climates; and one would have thought, that all the Turtle-Doves upon Earth had chose to pass thro’ this place. For the eighteen or twenty days that we stay’d there, I firmly believe that a thousand men might have fed upon ’em heartily, without putting themselves to any trouble.”

The pigeons’ feeding, as described by John Wheaton (1841-87), was accompanied by a deafening noise to one’s ears and confusion to an observer’s eyes. “In the fall of 1859 ... I had an opportunity to observing a large flock while feeding, The flock ... present(ed) a front of over a quarter of a mile, with a depth of nearly a hundred yards. In a very few minutes those in the rear, finding the ground stripped of mast, arose above the tree tops and alighted in front of the advance column. This movement soon became continuous and uniform, birds from the rear flying to the front so rapidly that the whole had the appearance of a rolling cylinder, having a diameter of about 50 yards, its interior filled with flying leaves and grass.”

When gathering such mast (acorns, etc.), a pigeon’s crop (the pouched enlargement of the bird’s gullet) could expand to the size of an orange, according to observers.

“The physical appearance of the bird was commensurate with its flight characteristics of grace, speed and manoeuverability (Encyclopedia Smithsonian). The head and neck were small; the tail long and wedge-shaped, and the wings, long and pointed, were powered by large breast muscles that gave the capability for prolonged flight. The average length of the male was about 16.5 inches. The female was about an inch shorter.

“The neck and upper parts of the male pigeon were a clear bluish gray with black streaks on the scapulars and wing coverts. Patches of pinkish iridescence at the sides of the throat changed in color to a shining metallic bronze, green, and purple at the back of the neck. The lower throat and breast were a soft rose, gradually shading to white on the lower abdomen. The irides were bright red; the bill small, black and slender; the feet and legs a clear lake red.

“The colors of the female were duller and plainer. Her head and back were a brownish gray, the iridescent patches of the throat and back of the neck were less bright, and the breast was a pale cinnamon-rose color.”

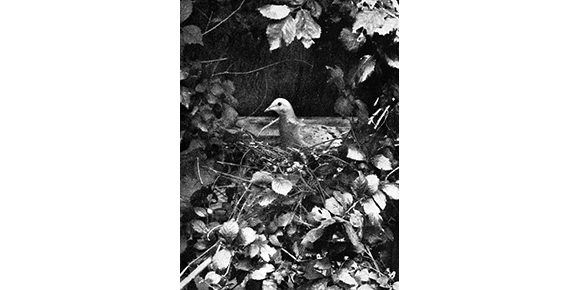

The mourning dove, which is common today, but nowhere near the numbers attained by the passenger pigeon, is the bird’s closest living relative, resembling it in shape and colour, although the dove is much smaller. Because of its similarities, mourning doves were often mistaken for passenger pigeons long after the latter went extinct.

What made the passenger pigeon particularly vulnerable to commercial hunters was its communal nature. The term “stool pigeon” arose from using a tethered live bird to lure other pigeons to the ground where they were then trapped in nets.

(Next week: part 4)