by Bruce Cherney (part 1)

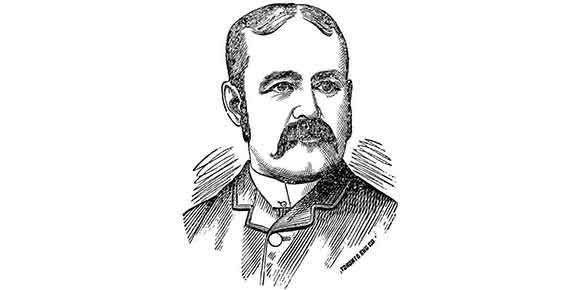

In Winnipeg’s early history, one of the most controversial figures in the young city was Colonel James “Jim” Sarsfield Coolican. For some, he was a scoundrel of the first order, while others regarded him as their personal angel of mercy. Indeed, he filled both roles quite admirably. And in the former instance, he was widely acknowledged as a good-natured and kind-hearted rogue. One’s impression of Coolican depended upon the deeds he was closely associated with — real or imagined — including his role in nurturing the abandonment of reason when promoting one of the most disastrous speculative booms in the history of Winnipeg, Manitoba and Western Canada.

Coolican is the man invariably singled out for criticism when the great land boom of 1881-82 abruptly ended in a recession and financial ruin for the many involved in what was in reality an artificially-inflated real estate market.

The ersatz boom was based upon the manipulations of Winnipeg’s silver-tongued auctioneers, including Coolican, who convinced gullible investors that the path to untold wealth lay in town lots they placed on the auction block. The belief fostered by the auctioneers was that these lots could be flipped over and over again for ever-increasing profits.

During the boom, many real estate transactions were through auctions and some lots had a reserve bids, though not the majority, as the auctioneers wanted the frenzy of the bidding to drive up prices. There were also real estate agents not operating out of auction houses who did place specific prices on lots and farm land offered for sale.

During the real estate boom from June 1881 to mid-April 1882, newspapers across North America and in Europe proclaimed that Winnipeg was the place to be, a real-estate bonanza for quick-buck artists.

“I doubt if to-day any other city on the continent, according to its population, can boast of so many wealthy young and middle-aged men,” said a reporter for the Toronto Globe in March 1882.

“Thousands of dollars were made by operators in a few minutes,” wrote J. Macoun in his book, Manitoba and the Great Northwest, published in 1882.

What prompted the real estate boom was the railway — specifically, the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1881. The first CPR train crossed the newly-built Louise Bridge into Winnipeg on July 26, 1881. Its destination was an “unassuming” 1-1/2-storey wood-frame depot at the corner of Main Street and Point Douglas Road, although there was nothing “unassuming” about the impact the CPR had on the real estate market.

And when the CPR came, it spent millions on a passenger station (the land was a gift from the city), freight sheds, a roundhouse and other railway-related buildings. Winnipeg became the main supply depot for construction on the westward expansion of the CPR to the British Columbia coast. The railway brought workers and settlers to open up the New West and they all passed through Winnipeg.

Also arriving in the trains were the inevitable opportunists. Ontarians came first, followed by Americans and Europeans, all of whom heard tales of a city paved with gold.

In 1882, one of CPR general manager Cornelius Van Horne’s first official acts was to place ads in local newspapers cautioning the public against purchasing lots based on speculative guess-work about where the CPR would set up stations along the rail route, which was a favourite ploy of the city’s auctioneers. He said townsites would be chosen by the railway and the railway alone, “without regard to any private interests whatever.”

The best example of what Van Horne meant was the townsite of Brandon. Initially, the CPR had wanted to cross the Assiniboine River at Grand Valley. People flocked to the alleged new town to snap up lots in anticipation of a new station and crossing being built. But the McVicar brothers, who owned the land got greedy. When their selling price steeply rose at the instigation of speculators, the CPR decided on a new site a few kilometres to the west which cost the railway a pittance. Grand Valley went bust while Brandon boomed to the satisfaction of the CPR. Whenever possible, the CPR would follow the model established at Brandon.

Van Horne’s warning was mostly ignored, especially by a gullible public willing to believe the outrageous claims of Winnipeg-based auctioneers.

“The excitement spread like wildfire all over the country. Cool-headed professors and businessmen (clerical as well as lay) left their callings in other parts of the country for the scene of the modern Canadian El Dorado,” said Macoun.

“Winnipeg is London or New York on a small scale,” wrote W.J. Healey in his 1927 book, Winnipeg’s Early Days. “You meet people from almost every part of the world. Ask a man on the street for direction, and the chances are ten to one that he answers, ‘I have just arrived, sir.’”

“Winnipeg was the centre of a boom, from which the evil radiated in all directions,” Alexander Begg, a local merchant, newspaperman and author, wrote in his History of the North West. “Towns were surveyed all over the Province and Territories, and lots in them were disposed of at auction at fabulous prices. The town site mania was aptly described by a railway conductor who had taken a trip to the end of the CPR track, on his return East. Asked how the country was progressing, he said: ‘Well it’s the greatest country I ever struck ... there’s a new town about every three miles from Winnipeg to Moose Jaw. Where there’s a siding, that’s a town, and where there’s a tank and a siding that’s a city.’”

It was a time when some enjoyed a precipitous climb to wealth and fame, although always looming in the background was the potential for an equally dramatic fall. “If ever there was a Fool’s paradise,” wrote George Ham in Reminiscences of a Recointeur, “it sure was located in Winnipeg. Men made fortunes — mostly on paper — and life was one continuous joy-ride.”

As the leading promoter of the “boom,” Coolican was after the fact noted disparagingly as being an “unscrupulous” land speculator. Coolican made a fortune by selling Winnipeg, Manitoba and Western Canadian lots — often in fictional towns created by his fertile imagination — at unsustainable prices.

Dr. George Bryce in his history of Manitoba (1882) described Coolican as “eloquent, aggressive, unscrupulous, and by advertising his sales without commonplace things called facts, undertook to ‘stampede’ — to use the language of the plains — the Winnipeg community.”

To be fair to Coolican, he, similar to many others, was simply caught up in the euphoric hedonism of the land boom, although more than anyone else, he was responsible for promoting the boom until its bitter and ruinous collapse.

On winter mornings when Coolican, who was known as the “Real Estate King,” walked to his real estate auction house — The Exchange, which stood at the northwest corner of Portage and Main (it was often referred to as “Coolican’s Corner”) — he wore a $5,000 seal-skin coat and matching hat. His fingers were said to have sparkled with diamond rings of even greater value. Other accounts noted that he carried a selection of valuable diamonds in a coat pocket.

Following a day of lot sales valued in the thousands of dollars, it was further claimed that Coolican was prone to bathe in a tub filled with champagne.

Coolican’s obituary announcing his death in Chicago, which appeared in the Free Press on April 12, 1902, noted that in The Exchange auction house, “his cheery voice could be heard, sometimes in jest, at most times in earnest, disposing of hundreds of lots in exchange for coin of the realm.”

The auctioneer obviously took great delight in his role in the land speculation fever sweeping the West. His advertisements in the Free Press proclaimed himself as, “The Boom Starter!”

Speculation wasn’t limited to Winnipeg lots. In bold-type advertisements, Coolican proclaimed: “Cartwright Leads Them All. Unquestionably the Best Situated Rising Town in the Province.”

Cartwright, named after Canadian finance minister Sir Robert Cartwright (1835-1912), is today just a tiny village near the North Dakota border.

In other ads, he offered for auction sale 600 lots in West Emerson, 500 in Rapid City and 600 lots in Gladstone, among a myriad of other locations.

Coolican sold 225 lots in High Bluff at an average of $19 each and a large portion of the Minnedosa townsite at an average of $32 per lot.

In a two-week period, he was said to have sold $1 million worth of property.

Terms for payment by purchasers were said by Coolican to be “liberal.” For example, at an 1882 auction, the terms were “10 per cent at time of sale, enough to make one-half of purchase money in three days, balance in 6 and 9 days at 8 per cent interest.”

Col. Kennedy, the city’s registrar of deeds, estimated in December 1882 that the year’s real estate transactions would total between $10 million and $12 million. “Most of the large transactions were in Main Street property,” he said. “The Hub corner changed hands several times. A few years ago a portion of that was purchased for $15,000, and the purchaser was considered to be crazy ... now it has sold for $115,000.”

Member of Parliament A.W. Ross, called the “king of land,” was another prominent speculator. In April 1881, he purchased some Main Street lots at $75 a foot and sold them in June for $100.

“People thought it a good spec., and I thought so too,” said Ross. “Within six months the same property went for $400 a foot.”

Real estate auctioneer Joseph Wolf, who was known as the “Golden Auctioneer” because he operated out of the Golden Hotel and Real Estate Exchange, was said to have sold a half million dollars worth of real estate in the first six months of the boom, much of it out-of-town real estate. For example, three nights in a row he heard bids and sold $133,000 worth of North Brandon lots. His personal worth was said to have been in the neighbourhood of $200,000.

“Col. Coolican made it his boast that he could sell anything from a hairpin to a city for ten times its value if he could get the ear of people with money enough to buy; his experience in the jewelry sales episodes of Winnipeg and Victoria (after the boom) and his success in realty handling at Winnipeg, Gladstone, Minnedosa, Edmonton, High Bluff, Poplar Point, Darlingford and Grassmere (during the boom) went a long way toward proving that he was not wildly egotistical of his own powers of persuasion,” according to his obituary that appeared in the Vancouver Daily World on April 16, 1902.

(Next week: part 2)