by Bruce Cherney (part 4)

In September 1906, E.F. Hutchings, of the Manitoba Exploring Co., said water from a St. Boniface artesian well would be transported across the Red River to Victoria Park via pipes where he proposed to build a public bath. He informed Winnipeg city council that the company’s well was located a mile (1.6 kilometres) from Victoria Park and water flowed “full stream” through a four-inch pipe.

Its salt and high mineral content made it a good source of water for the facility, he added.

Besides a swimming pool, said Hutchings, there would be private baths. Surprisingly, he said the salt water was also good for drinking.

The Manitoba Exploration Co. request wasn’t acted upon, but over the course of three years, there continued to be discussions about public baths at Victoria Park.

In 1908, Charles Wallace Sharp, a member of the parks board, advocated that Victoria Park, at the foot of Rupert Avenue in the city’s downtown, be abandoned and a public bath be erected on the property, but again no action was taken by city council.

It wasn’t until the municipal election in December 1909 that ratepayers approved $50,000 in spending for a public bath by a 1,958 to 880 vote

In 1910, architect William Bruce submitted a public baths plan to city board of controller, Richard Deans Waugh, who made his own suggestions for additions, such as separate showers for children, locker rooms and an examination room to prevent anyone with a contagious disease from entering the baths (Tribune September 10, 1910).

The Board of Control, established in 1907, dealt with all financial matters and generally managed the affairs of the city until it was abolished by referendum in December 1918.

The water used in the swimming pool (then referred to as a swimming tank) would be changed three times a week to prevent the formation of “scum,” according to Waugh.

Waugh said the site for the public baths had not been definitely decided upon, but it would be in one of the city’s parks.

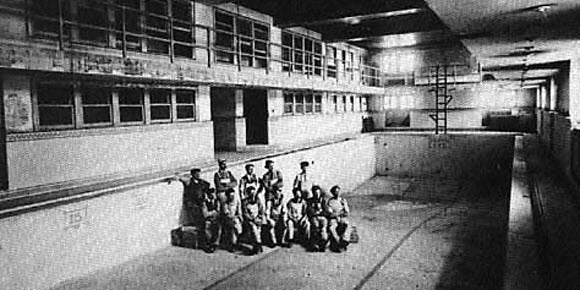

In the end, Victoria Park was spared and three-acre Selkirk Park, established in 1894, became the site of the recreational facility, which became known as the Pritchard Avenue Baths. The swimming and bathing complex officially opened on May 6, 1912, at the corner of Pritchard Avenue and Charles Street.

In 1913, the city’s parks board proposed that Victoria Park be sold to the private sector, saying it and other park land had to be sold, since the board had no other way of raising needed funds after the parks bylaw referendum had been defeated during the municipal elections.

Alderman (councillor) Robert Shore, a member of the parks board, told Winnipeg council that if the city didn’t want the park to once again become private property, the board was willing to sell it to the city for its assessed value of $150,000.

“Should you desire to obtain possession of this property rather than have it disposed of to other parties, we shall sell it to you on conditions that you take care of our deficit on capital account at present in the neighborhood of $96,000 and credit our revenue account with the balance,” wrote parks board chairman F.W. Handel in a letter to council.

The majority of city aldermen objected to the proposal and it fell by the wayside.

During the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, many of the 35,000 men and women strikers, as well as their supporters, gathered each day at Victoria Park. On the morning of May 16, thousands were at the park to hear William Ivens, the socialist editor of the Daily Strike Bulletin and minister of the Labour Church, urging them not to give up their battle for fair wages, better working conditions and collective bargaining. Every Sunday, during the strike, Ivens would hold Labour Church services and relay news of the strike’s progress.

The central location of Victoria Park was the ideal point to organize and begin strikers’ parades and marches, although Mayor Charles Gray had issued a proclamation forbidding public demonstrations on the city’s streets.

When 6,000 people left Victoria Park at noon on June 6, they were met by Deputy Police Chief Chris Newton, who with five constables blocked Rupert Avenue in front of the Winnipeg Police Station (it no longer exists). Those participating in the parade were described by newspapers as being orderly and offered no resistance to the police.

C.E. Bray, leader of the parade of returned First World War soldiers, and five others, were arrested, but were soon released when they promised Police Chief Donald MacPherson that they would take the marchers back to Victoria Park.

The labour movement lost the strike, but Victoria Park continued as the primary meeting place to discuss the issues of the day and protest perceived injustices against workers.

The Tribune on May 28, 1920, announced that a labour protest was planned for Victoria Park on June 6.

“Victoria Park, which achieved fame as a rendezvous for strikers last summer, again will be become a centre for labor activities,” reported the newspaper.

People were to gather at the park to protest the continued incarceration of the leaders of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike. Eight alleged strike leaders arrested on June 18 were charged with sedition. Of their number, the charges against James Shaver Woodsworth were dropped, Fred Dixon was acquitted, Sam Blumberg fled to the U.S. under threat of a deportation order, while five others, including Ivens, received jail sentences ranging from six months to two years.

According to the reporter, “It was in this park that the men whose imprisonment is to be protested uttered much of the alleged sedition complained of in the charges against them.”

It was reported that 500 to 600 people attended the June 6 meeting in Victoria Park, with all the speakers calling for the release of the imprisoned labour leaders.

(Next week: part 5)