by Bruce Cherney (part 2 of 2)

Edwin Kelsey’s Helicopter didn’t make it past the model stage. Although the model flew, there was no attempt to build a full-scale version. The photo of the model (see last week’s Real Estate News) in the Winnipeg Tribune, called a “dirigible helicopter,” is quite blurry and it’s hard to get a proper understanding of the machine, but it looks quite flimsy and more childlike in its construction than practical for conversion into a larger version. In fact, it bears

little resemblance to a dirigible or a helicopter. The photo shows the paper “windmill” rotors extending from the main body of the “aircraft.”

Flying Era is Now at Hand: Wonderful Advance in the March of Human Achievement — A Local Flying Machine was the headline in the June 21, 1909, Winnipeg Tribune. Under the auspices of the Aero Club of Canada, Kelsey and William J. Robertson had turned their attention to building a

biplane. In all subsequent reports, Robertson is claimed to be the principal inventor of the aircraft and no further mention is made of Kelsey.

According to the newspaper, the “aeroplane” had “many new and important features designed for stability of flight and facilities for manoeuvreing.”

The description provided was that the biplane had an upper deck surface of 28-by-six feet “corrugated into three triangular grooves with their apexes upward. The lower plane is similarly constructed, but the central groove is

replaced by a boat-shaped car in which the engine and aeronaut are placed.

“The machine is steered by the deflection of special planes, of which there are four, placed one in each of the gutter grooves of the corrugations. These are capable of being operated in both horizontal and vertical pairs; the vertical pairing giving a turning effort, while the horizontal pairing gives the necessary tilting, or rising, or falling efforts to the plane.

“The whole will be driven by a 15-h.p. Curtiss motor of 1,800 revolutions per minute, which is reduced by sprockets and chain to 450 revolutions on the propellor, which consists of two four-foot blades of pterygoidal or wing-shaped surfaces; this placed at the front of the machine.

“The central corrugation of the upper plane is extended some four feet back in a short tail to obtain the full benefits of the propellor currents.”

The biplane, called an “Aerocar” and named Canada, was revealed to the public at the Happyland amusement park (opened in 1906 between Portage Avenue and the Assiniboine River in the city’s West End, but converted into residential lots in 1922). Advertisements claimed the aerocar would be flown on July 15, 1909. Meanwhile, it was its inventor, Robertson, who dubbed the

biplane, Canada.

“I want it clearly understood,” Robertson told a Manitoba Free Press reporter (published July 15), “that I do not guarantee a really successful flight to-night. Owing to the non-arrival of material from the United States, and the impossibility of getting certain parts made at short notice in Winnipeg, I have not been able to get my special lifting

device ready for to-night’s flight. This device is designed to lift the Canada fifteen feet off the ground. With my light fifteen horse power motor, which is ten horsepower less than other aeroplanists are using, I hardly expect to get sufficient power to-night to get up safely in such a circumscribed area as Happyland.”

Indeed, aviators were using at least 35-hp engines in their airplanes by 1909. As a motorcycle manufacturer, Glenn Curtiss in 1907 had developed a 40-hp, V-8 engine. The air-cooled, F-head engine had been intended for use in aircraft.

The American-born Curtiss was a member of inventor Alexander Graham Bell’s Aerial Experiment Association (AEA) based in Nova Scotia and designed its June Bug, which successfully flew for over 1.6 kilometres using one of the V-8 engines Curtiss designed on July 4, 1908, in Hammondsport, New York. The engine was rated at 40-hp. Curtiss’ “long-distance” flight won the Scientific American Trophy.

The newspaper added more information on the configuration of Robertson’s biplane, saying it was “constructed on entirely novel principles as far as the ‘V’ shaped planes are concerned and has a steering rudder of absolutely new design, is not in other respects opposed in its general principles of construction to those of machines which have made successful flights.”

Instead of the 28 feet mentioned by the Tribune, a Free Press reporter said the machine was 30 feet long. But both reports indicated the biplane was six-feet wide. The latter newspaper’s reporter said the propellor was seven feet across.

“I have devised a travelling carriage for the machine for temporary purposes,” Robertson told the Free Press reporter, “and when the propellor is making its revolutions at full speed the travelling carriage will be released and force the machine forward at a high rate of speed. If I can get a speed of thirty miles an hour the planes (wings) should enable me to arise sufficiently to clear the Happyland fence and make a successful ascent. The fence is too near to give a fair start to the machine when attempting a flight under these conditions, but I am very hopeful the lightness of my machine, which weighs some 700 lbs., less than that of the Wright Bros., may enable me to overcome all these difficulties. If I am mistaken, I shall make another and more certainly successful trial as soon as my lifting apparatus is completed.”

The Wright Flyer of 1903, also a

biplane, weighed 605 pounds (274 kilograms) empty and had a maximum weight of 745 pounds (338 kilograms) for takeoff. It had a straight-four water-cooled engine that developed 12.5-hp that was designed by the two brothers. Of course, the Wrights’ later models

developed more than 15-hp. The Wright Model A in 1909 had a 35-hp power plant.

Unfortunately, the Winnipeg newspapers failed to include pictures of what the Canada actually looked like, which leaves the airplane’s configuration to the imagination of the reader.

The general concensus is that it resembled in some ways the Curtiss biplanes of the day.

The first advertisements mentioned the flight was scheduled to take place on July 14 at 3 p.m. Standing room “at personal risk” was 25-cents each, bleacher seats were 10-cents “extra,” while grandstand seats were 25-cents extra. Children paid 25-cents each for any seat.

But as mentioned above, by July 15 the public trial flight had yet to take place for the reasons provided by Robertson.

In fact, the trial never occurred, and the flying machine never took to the air, despite the assertion that Robertson’s machine was “as superior as is claimed to those which have flown in the United States, England and France. Many who have seen it believe that the Canada will only justify its name” (Tribune, July 15, 1909).

By this time, numerous aviators had successfully taken to the air with aircraft of their own design. The more famous of the era were the Wright Brothers, the AEA membership, including Glen Curtiss, and Louis Bleriot from France, who was the first aviator to fly across the English Channel in 1909. He was also the first aviator to successfully fly a monoplane on November 16, 1907. In fact, their aerial feats and the type of aircraft they used would have been well known in Winnipeg, which makes it all the more surprising that successful aircraft were not built, despite the goal of the Aero Club of Canada.

Mind you, some of the ideas put forward by so-called inventors were outright wacky, such as Kelsey’s plan to build an ornithopter, or a wing-flapping machine, he believed would fly like a bird. In early aviation, creating such a machine was attempted time and time again and always failed miserably. They were also frequently very dangerous to the “birdman.”

Even Robertson’s idea to use a lift mechanism to get his biplane airborne due to an under-powered engine borders on the strange. Occasionally, catapult mechanisms were used to get early aircraft into the air, but the planes always started out on the ground. The Wright Brothers used a weight dropped behind the biplane that pulled a cable along a rail system firmly anchored to Mother Earth to achieve enough momentum to get their aircraft into the air. Steam-powered catapults and a rail system are used on most of today’s aircraft carriers for the same purpose.

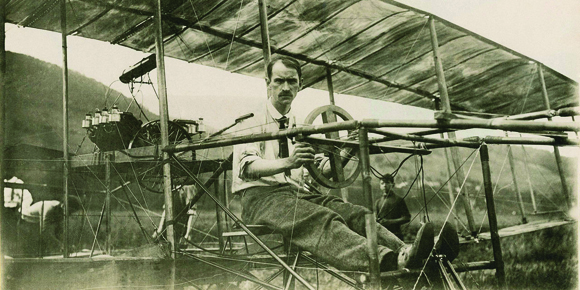

On Friday, July 16, 1910, a Free Press headline read First Aeroplane Flight in Western Canada. The accompanying article announced that at dusk the previous day, American Eugene Ely’s four-cylinder Curtiss biplane finally took to the air to the great relief of the Winnipeg Industrial Exhibition management. The successful flight took three attempts with the first two resembling “a bird with a broken wing.”

“The wind, which had been blowing at twenty miles an hour, finally calmed as darkness descended and the aviator described a circle of two miles (3.22 kilometres) at a height of forty feet (12.19 metres). He soared like a great bird and came within one hundred feet (30.48 metres) of the starting point when the engine suddenly stopped. Then came one of those glides that people read so much about, and Ely swooped down to the ground so sharply that the left plane (wing) struck the uneven surface and broke two ribs of the airship and some stays ...

“Eugene Ely, calm and collected, stepped from his seat and gave directions for hauling the biplane back to the grounds.”

What Winnipeggers had hoped to accomplish first in their city and in Western Canada was usurped by an American flying an American-built aircraft.

It wasn’t until 1915 that a locally-built airplane made a successful flight.