Cooler than normal weather — 21°C on Tuesday. Seemingly, continual rainfall. It hasn’t been a particularly good week weather-wise. July in Winnipeg and Manitoba should be relatively sunny and balmy, but the month hasn’t quite lived up to its summer-time reputation.

Still, it could be worse, as it was in 1936, when the city and province was in the midst of a deadly heat wave from July 5 to 17. During that period, the temperature averaged 36.4°C and the hottest day in Winnipeg was a scorching 42.2°C.

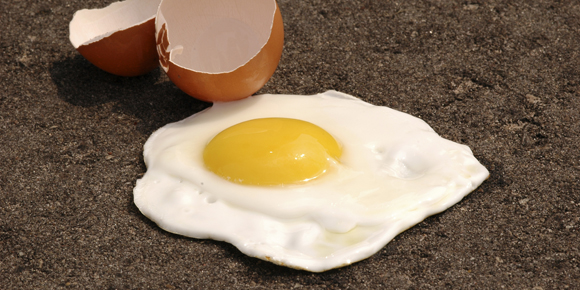

It was so hot that on at least two occasions, people attempted to visibly prove the heat was relentlessly intense.

“There was a sort of general impression that it was pretty hot in Winnipeg Tuesday,” wrote the Winnipeg Tribune’s Vic Murray on July 9, 1936. “In fact, a lot of people went around saying it was hot enough to fry and egg on the sidewalk.”

Murray resolved to conduct the culinary experiment on the sidewalk outside the Tribune Building. At the time, Murray reported that the temperature had hit 111°F ( 43.8° C, so it was unofficial).

“I tried to fry two eggs and an order of bacon on the north-west corner of Smith St. and Graham Ave. ... The first egg was cracked at exactly 3:59 p.m. ... The cracking took place in the presence of a gathering of small boys and curious adults. It was what is known as in some circles as a scunner. In other words the yolk became unyolked.

“The second egg plopped down intact but immediately tried to run away. It was not until it was buttressed by a couple of pieces of bacon that its roving instincts were curbed.”

Murray wrote that by 4:02 p.m., the onlookers had become so numerous that a police constable appeared on the scene to inquire what was going on.

“We’re just trying to fry some bacon and eggs on the sidewalk,” Murray explained.

The constable was said to have been somewhat dubious about the eventual outcome, and was more inclined to believe Murray’s experiment was a public nuisance, but allowed it to continue.

“Five minutes passed without any sign of progress. The scunner egg had started to stiffen but this was probably due to the hot breeze passing over it.

“‘It’s drying, not frying,’ said a bewhiskered gent, with a tattered hat, who seemed to know what he was talking about.”

Murray reported that the cooking progress was so slow that many of the onlookers began to leave.

Seeing those who remained on the scene, an elderly lady passer-by inquired: “What’s the matter? Has someone fallen off the roof!”

Of course, her comments arose because of the mess on the sidewalk that bore little resemblance to fried eggs and bacon.

Murray soon afterward gave up on his experiment. Vince Leah, a fellow reporter for the Tribune, wrote in his 1975 book, Pages from the Past, that “the bacon had melted into a useless mess and the eggs were blackened and dried up.”

The second experiment to create a fried egg sandwich was related in the Winnipeg Free Press on the same day and involved members of the Big Game Hunting, Fishing, Flood Experting and Physical Research department. In this case, the experiment was moved to the pavement.

“The eggs just wouldn’t fry,” reported the newspaper. “While the golden slowly coagulated, or whatever it is that egg yolks do, the white flowed off in the general direction of the curb.”

The bread also failed to toast.

“You can’t fry eggs on the street,” was the conclusion reached.

But while reporters tried to inject some humour in the midst of the heat wave, it was far from a laughing matter.

In an era before households and buildings were cooled by air conditioning, Leah wrote that it caused the deaths of 31 people, hospitalized 40 more and wiped out crops and livestock.

There had been some signs that the heat wave was on it’s way, according to Leah. “There had been no rain for a long time. Farmers viewed their faltering crops with consternation ...

“As the heat grew in intensity, people became ill, collapsed with heat prostration and the emergency wards of Winnipeg’s hospitals suddenly became active. It was a particularly trying time for invalids and elderly people.”

People trying to find relief at Manitoba’s beaches on July 11, when the heat was at its greatest intensity. Unfortunately, “the death toll from drowning was staggering and on that day alone nine persons lost their lives,” wrote Leah.

On July 11, sports events were cancelled and hundreds of shops and offices closed their doors. To escape the heat, people took to their cellars.

“Many people did not go to bed ... They sprawled on their lawns, on fire escapes or in the public parks, for the coming of darkness did not alleviate the scorching temperatures.”

The heat was particularly hard on delivery wagon horses, which were still common on Winnipeg’s streets. Leah watched from a Dufferin Avenue streetcar as one horse slumped and died between the shafts of a junkman’s wagon.

There was a rush to buy cheap hats, he wrote. Holes were made for horse’s ears, “and hundreds of horses went about their business looking rather quaint and whimsical.”

Ice cream and soda pop shops did a booming business.

“On Main Street, near the Higgins Avenue subway, the asphalt melted and the odd automobile sank to the rims. The iceman’s wagon, a familiar sight in the summer before modern refrigerators, were trailed by legions of small boys and girls, scrambling for ice chips.”

It was said that boys and girls went into the lemonade business en masse.

Movie theatres with air conditioning — one of the few locations with such a service in the city — were well patronized, while those without languished.

By mid-July, the Tribune was reporting scattered rain showers to the west, which were believed to be on their way to Winnipeg and promised to provide some relief from the relentless heat.

In fact, the July 13 newspaper reported what had been scattered showers had turned into violent thunderstorms with deadly consequences. Some relief was provided, but at a price and it was only temporary. “The record-breaking heat wave of the last nine days was eased for Manitoba and Eastern Saskatchewan Monday night by thunderstorms that killed one man near Winnipeg, injured two, and did much property damage in the city ...” The heat wave continued as clear skies hovered above the prairies.

“In Winnipeg, Saturday’s high of 84 (28.8°C) was 24 degrees (16.6°C) under the all-time high reached a week before,” reported the Monday, July 20, 1936, Tribune. The high temperature on Sunday was “only” 88°F (31°C).

After two weeks of blistering temperatures, the deadly heat wave was finally at an end.

Today, air conditioning has made us soft. How would we have coped in July 1936?