by Bruce Cherney (part 3)

Albert “Ginger” Snook related that he had imposed order in his Canadian Northern Railway gang by always carrying a pick handle. Along with his large physical presence, he used the pick handle to “argue” the railway’s cause when confronted by rebellious workers. Snook couldn’t be accused of walking softly while carrying a big stick, and his use of the implement in meting out punishment became the stuff of legend.

“On one occasion the grub had been bad. The expected provisions had failed to arrive. The pay car was behind time. His gang wanted to quit” (Winnipeg Tribune, November 18, 1926, obituary).

Snook described the situation as “awkward,” and he “had to lay about 20 of them out” — undoubtedly, an embellishment of what actually occurred. It should be noted that Snook was often prone to outlandish exaggeration in order to make a point.

Even his great-great-granddaughter, Adrienne Owens of Chesterfield, Michigan, admitted in an email that her own research revealed that he was “such a character” that she wouldn’t be surprised that portions of his life story were “made up.”

The pick wielder was later in charge of a “mud gang,” which was assigned to replace grades washed out by heavy rains in the mountains. During one particularly brutal storm, the grades were entirely carried away. “To make matters worse the entire gang had been out carousing all night. Those were the days of the frontier town with gambling and drinking mere incidents in a day’s work and a night’s debauchery.”

With pick handle in hand, Snook assembled his gang. They got as far as the Kicking Horse River when the train driver lost control of the engine and the work train went into a spill, resulting in the death of one man. The engineer broke his collar bone and several men received minor injuries. Snook gathered himself up, took stock and announced his hand was broken and he had “two lovely black eyes.” His gang returned to work, but he was out for the summer.

Another time, a man was killed in an accident and Snook’s gang blamed the engineer and threatened to lynch him.

“Ginger and his trusty pick handle arrived in the nick of time.”

When he confronted the men, their leader explained that the accident was the engineer’s fault and that their desire was to lynch the alleged murderer.

Snook argued against the death sentence, but made no headway in his arguments towards appeasement of the thorny situation. “His English rose and he smote the leader over the head with the pick handle.” Tempers then flared and several knives appeared in the hands of the crew, “but the flaying pick handle — an excellent shillelagh by the way — soon mowed down the lynchers who departed leaving many casualties on the field.”

It wasn’t until 1887 that Snook returned to settle permanently in Winnipeg.

Snook was said to have first lived in a shack where the present historic Ambassador Apartment Block, 379 Hargrave St., now stands, claiming squatters rights (Memorable Manitobans: Albert Robert “Ginger” Snook, 1835-1926).

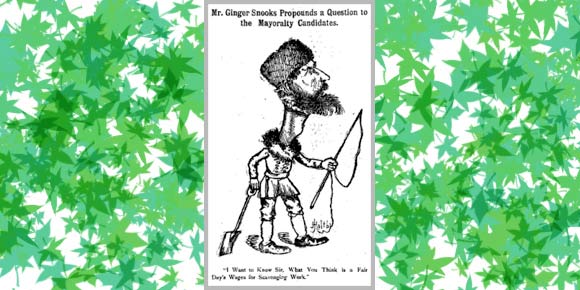

Snook’s working career in Winnipeg began with his appointment as the city scavenger. Using a team of horses drawing a wagon and with a shovel in hand rather than a pick handle, he collected waste from city stables and the outhouses lining backlanes at a time when the city’s water and sewage system was just coming into existence. In the process, Snook cleaned up in two ways: he took away the manure from city stables and later sold it to householders to fertilize their gardens.

Snook advertised in the city’s newspapers that he cleaned “closets” — outdoor privies — and removed garbage “at reasonable rates,” and offered prompt attention “when citizens are notified by the health department” of the city (February 13, 1902, Tribune).

Col. G.C. Porter in his April 9, 1938, Tribune column, The Oldtimer Talks, wrote that once Snook had his city scavenger contract he became a man of means, eventually branching out into real estate and trucking and in the process amassed a fortune of several hundred thousand dollars. He had at his disposal a fleet of “honey wagons” with accompanying horse teams, which he also occasionally hired out to the city as draft animals for asphalt paving projects.

It was said that as his wealth increased, “his dress and personal appearance became proportionably more objectionable.”

Snook was noted for neglecting to change his clothes after a shift of collecting “night soil” when he attended public meetings. One whiff invariably sent those on the stage with him scurrying for shelter from the assault on their sense of smell.

As a real estate agent, he put up one particular house on the market with a sign saying, “This House For Sail.”

A passerby wanting to inject humour at Snook’s expensive, asked him when he was going to “sail” his house down the street.

“Just as soon as some dam fool like you comes along and pays me twice what it’s worth. Now get off this property before I pitch you in my garbage wagon and dump you in the sewer.”

Arguably, no one in Winnipeg’s early history garnered more newspaper copy than Snook when attacking city hall, the board of control and the health department. His opinion on a variety of other topics was also sought, since he was a self-proclaimed expert on almost everything deemed newsworthy. Apparently, no cause escaped his attention, nor the wrath of his barbed tongue. His language was deemed to be “foul” — laced with expletives of every imaginable fashion — but this was excused since he was simply “Ginger,” the well-known “eccentric character.” Even the courts weren’t immune from the ire of Snook, who became a regular in the docket as a witness or a defendant.

(Next week: part 4)