A vivid memory from my university days was arriving at my mother’s and father’s Gimli home on a Friday evening after a week of classes and seeing that their kitchen was filled with people of various ages speaking an unfamiliar language. They were of obvious Southeast Asian descent, but I didn’t know then if they were Cambodian, Vietnamese or Laos. During this first encounter, I soon learned they were Vietnamese.

My mother, using a smile that was always present, seemed to have put them at ease, and was being a genial host, having made coffee — a foreign beverage for tea drinkers — and placed out a platter overflowing with cookies and dainties. I sat down and joined the group gathered around the cramped quarters of the kitchen table. One of the group was able to haltingly interpret for my mother, who listened patiently and then posed her own questions.

Why was my mother playing host to a group of Vietnamese boat people in 1979? Well, she was the local representative of Canada Manpower and by extension one of the few federal civil servants in the area. She may not have been responsible for the settlement of the boat people, who fell under the auspices of local church and community organizations, but she was a federal employee and Ottawa had earlier announced its intent to settle tens of thousands of Vietnamese refugees in Canada.

The people also wanted jobs and, although my mother was only supposed to work five days a week from Monday to Friday, they dropped in on any weekend day to pay a visit with the lady who listened so patiently to their problems of adjusting to a new life. Following that first encounter, I can remember frequently answering a knock on the door on any given Saturday or Sunday. The hopeful Vietnamese would express their desire to speak with, “Thorey.” They couldn’t quite pronounce this given name, but they tried their best to master her strange-sounding name that was not even rooted in English.

The continual interaction my mother had with the boat people arose because Canada was then in an economic downturn and the Gimli area had few jobs to offer them. As well, they were having trouble adjusting to Canadian customs, which they hoped my mother would explain to them.

Eventually, the most obvious and necessary outcome was that the Vietnamese first settled in Gimli were placed in cities where jobs were more readily available and other opportunities to adjust to Canadian life existed.

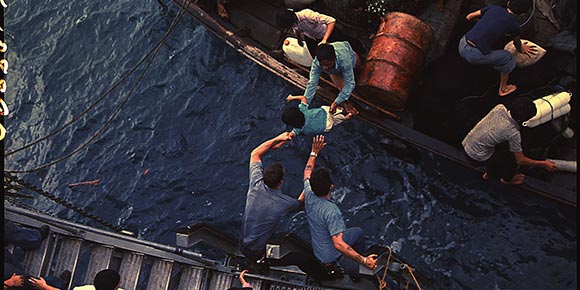

Canada’s response to the boat people from Vietnam came after people saw news reports of refugees crammed aboard flimsy and leaking boats. At the time, the perception was that the Canadian government had an obligation to alleviate their dire circumstances. During nightly newscasts, Canadians were told of the harsh conditions endured by the refugees. In 1978, the tragedy of a boat named the Hai Hong , as it drifted from port to port with 2,500 Vietnamese refugees onboard, was seen every evening on Canadian televisions. It was a ship that no country in Southeast Asia allowed to land.

For Canadians, it was a reminder of the 907 Jewish refugees aboard the doomed St. Louis. Canada was among the many nations which refused to give the Jews asylum, which meant that the ship returned to Hamberg with its passengers, resulting in most being murdered in Nazis death camps. Canada had the worst record among Western nations when it come to granting a haven for Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler and his Nazi cronies. Infamously, one Canadian official, when asked about how many Jews should be admitted, replied, “None is too many.” Anti-Semitism was rife among the highest bureaucrats in the federal government. Canada only grudgingly accepted 4,000 Jewish refugees, while the U.S. took in 240,000, Britain another 85,000, China 25,000, and Argentina and Brazil over 25,000 each.

It was also the memory of this failure that in part led to Canada granting asylum to 37,000 refugees in 1956-57 after the Hungarian uprising was brutally put down by Soviet tanks and troops.

Yet, not all went smoothly in this instance, as related by a January 4, 1957, Free Press editorial, which claimed that immigration officials at the refugee camps in Austria, where the Hungarians had fled from the Soviets, were granting few visas. Ottawa said it would accommodate just 24,000 refugees, which was a change from its formerly stated “wide-open door” policy. Apparently, the change occurred in response to “prejudices.”

“No (official) announcement of this change was made,” according to the editorial. “Word of it came first from Vienna where long queues of refugees waited, without success, for visas.” The newspaper issued a humanitarian appeal that the policy be changed: “If there is the will, the means are not difficult to find.”

Today, an image of a face-down three-year-old in the sand with the surf lapping against his still body, has again instilled strong emotions in Canada about the plight of another group of boat people — the many thousands fleeing civil conflict in Syria. Alan Kurdi was found on the Turkish beach. His brother Ghalib and their mother Rehanna also drowned trying to flee by boat to the Greek island of Cos. The sole family survivor was the grief-stricken husband and father, Abdullah. The image struck Canadians harder when it was discovered that the dead boy on the beach had an aunt, Tina Kurdi, living in Canada. She tearfully said she is attempting to bring her remaining family members to safety in Canada.

Such horrific images tug at the hearts of observers. In Canada, the outcry has been to bring more refugees to this nation as quickly as possible. France and Germany have already pledged to take in an additional 55,000 refugees over the next two years. Britain also announced plans to resettle thousands of refugees.

In a Canadian Press article, former Prime Minister Joe Clark said he believes Canadian officials can overcome any obstacles and speed up the acceptance of Syrian refugees, as was the case when his government brought over the Vietnamese boat people. Clark sent thousands of officials overseas to process applicants living in crowded refugee camps. Any fears of Communist infiltrators arriving in Canada were allayed by the screening process, he added. “The possibility there are some people (Syrian refugees) who are not who they claim to be should not deter us at all from proceeding with a very vigorous strategy of identifying people and getting them here quickly,” Clark said.

In the same article, Ron Aykey, who served as Clark’s immigration minister, said the existing systems for the Syrians haven’t matched Canada’s response in previous crises. “You send the application in to Ottawa and they take a year to deal with it,” he said. “These people are in camps in Jordon and Turkey and they may not make it.”

In the midst of a federal election campaign, the message coming from many Canadians is that we can and should do more, as we did for the Vietnamese refugees in 1979-80.