by Bruce Cherney (part 1)

It may surprise many Winnipeggers that it took six decades to resolve the conflicts that hindered the construction of the city hall that now stands along Main Street.

As early as 1905, it was recognized that a new city hall was needed. In that year, the July 6 Winnipeg Tribune reported that “accommodation for the civic offices is not sufficient ... A number of civic officials are practically without office accommodation.”

Mayor Thomas Sharpe told a Tribune reporter (published November 15): “I believe that the present city hall is much too small and that the civic business is suffering in consequence.”

Sharpe was disappointed that city council changed its mind and failed to pass a bylaw that would have allowed a debenture to build a new city hall being voted upon by ratepayers in a referendum.

Even the location of a new city hall was up in the air for 60 years, although the plans for a replacement in 1911 favoured the existing Main Street location.

In the spring of that year, city council discussions centred on what form the new city hall would take. At first, there was talk of an entirely new complex being built at the earliest possible opportunity, but that changed to a phased construction plan, commencing with an annex on the site of the city market behind city hall.

The concern expressed in 1905 was again at the forefront in 1911; that is, the existing city hall had inadequate space to house the city’s various and growing departments. As a result, office space had to be rented in downtown buildings for the burgeoning bureaucracy.

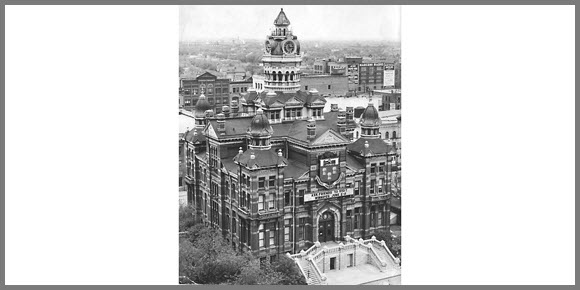

When the Victorian “gingerbread” city hall was completed in 1886, the city had only 20,238 residents. By 1901, the population had doubled to 42,340 and then hit 136,035 when the proposal was made to construct a new city hall in 1911 (Winnipeg’s City Halls 1876-1965, by Alan F. J. Artibise, Manitoba Pageant, Spring 1977).

An editorial in the November 10, 1911, Manitoba Free Press stated that “Winnipeg ... has grown at greater proportions than were anticipated when the present city hall was constructed, or when the space allotted for municipal buildings were fixed ... The present building has long been deficient in space for actual municipal requirements.”

Artibise wrote that this was a period when ideas of “civic grandeur” were widespread in North America.

“These ideas usually expressed themselves in advocacy of grandiose public buildings; buildings meant to serve two purposes. First, a grand civic centre would introduce beauty into the city.”

But more importantly, Artibise wrote that a new city hall would instill civic pride, during a period when architecture was meant to communicate ideas and possess symbolic implications.

A Free Press editorial made the same point, stating that the proposed city hall “should be an ornament to the city.”

At a city health committee meeting on May 11, 1911, Alderman (today’s councillor) John James Wallace suggested steps be taken to build an annex as soon as possible.

“I hesitate about incurring the expense at the present time,” he said, “but the accommodation we have for our departments at present is a disgrace, and I don’t blame the heads of departments for being ashamed to show visitors through. We have for the health department about the worst quarters and the finest civic exhibits of any city in North America. The city is growing very rapidly, and something has to be done” (Winnipeg Tribune, May 12).

The health department was actually housed in the basement at city hall.

The result of the meeting was a resolution urging city council to approve the construction of “an office annex to the present building upon the property owned by the city in the rear of the present civic offices. Such an annex when completed (is) to conform to a general plan and be a portion of (a) new city hall on (the) present site.”

The June 9 Tribune reported that controller J.G. Harvey had been instructed to interview the president of the architects’ association, J.A. Atchinson, and ask him to sketch rough plans for a new city hall. The total cost of the new building was projected to be $2 million. Construction of the annex was included in the price tag. The plan was to eventually tear down the existing city hall to make way for a new building, a move said to be years in the future. The civic complex would extend from Princess to Main street, with King Street being bridged over from the first or second floor.

In the Tribune on November 11, Mayor William Sanford Evans expressed his opposition to just building an annex without a complete plan for a city hall being made available, which was an opinion echoed by a number of other members of council.

J. Pender West, the secretary of the Association of Manitoba Architects, in a November 9 letter to the Free Press, agreed with Evans. “Apart from the question of site, the proposed scheme appears ill-considered and inadvisable.” He called it absurd to construct a small section before the entire city hall was designed.

The same association passed a June 15 resolution protesting the erection of an annex before the report of the Civic Planning Commission had been presented to city council. But by the end of the year, the association had reversed its stand and its membership was in favour of building the annex.

City council unanimously passed a bylaw for $300,000, which was to be put to a ratepayers’ vote in a referendum on December 8, 1911. The bylaw going to the ratepayers was only for funds to build an annex.

J.G. Harvey, a member of the city’s board of control (the board, established in 1907, dealt with all financial matters and generally managed the affairs of the city until it was abolished by referendum in December 1918), had a different opinion about city council’s approval of the bylaw. If later passed by the ratepayers, he said the money would be used in 1912 to advertise an architectural competition for plans to build an up-to-date city hall and offices, as well as a large auditorium. The $300,000 was a starting point with more money to be asked for from time to time as the work progressed (letter to the Tribune printed on November 27, 1911).

The hopes of even building an annex for a new city hall were shattered when Winnipeg’s ratepayers — only those owning property valued at $400, which represented a small segment of the city’s population — voted 2,728 to 2,162 against the money bylaw.

But that wasn’t the end of the fight for a new city hall. Winnipeg’s City Planning Commission again recommended in January 1913 that a new city hall be built.

According to an article in the February 1, 1913, Manitoba Free Press, the planning commission recommended that “the present city hall and market site be transformed into a public square similar to St. James Place, Montreal.”

The commission wanted the construction of the new city hall to begin “this year.”

The results of an architectural design competition for a new city hall appeared in Winnipeg newspapers on March 3. The firm of Clemesha and Portnall of Regina won the competition and its $5,000 first prize, while Woodman and Carey of Winnipeg finished second and received $3,000 in prize money. A total of 39 designs were submitted for the competition.

The design of the six-storey building, surmounted by a clock tower in the “campanile style,” was described to be in the overall “Doric classic style,” and was projected to cost about $3 million.

The principal front of the building would face Main Street and it would extend over King Street with a 60-foot arch to keep the street open to pedestrian and vehicle traffic. The plan called for a building 495 feet long and 145 feet wide.

Critics of the proposal said that the project was too costly and that another site should be used rather than the existing city hall location.

Winnipeg’s Town Planning Commission indicated its preference for the Manitoba College location at 435 Ellice Ave.

It was pointed out to the critics that the existing site had to be used for civic purposes or else. Under the terms of the land sale to the city, it would revert to the trustees of the Ross estate to which it originally belonged, if not used for civic affairs.

The property deed held by the city was dated June 7, 1875.

(Next week: part 2)