by Bruce Cherney (part 5)

One of the strangest outcomes of an event in Victoria Park occurred in 1921. After attending and speaking at a Labour Church meeting in Victoria Park, W.D. Bayley, principal of King George School, was dismissed from his position by the St. Boniface School Board for comments reported in the Free Press on August 8. According to the article, Bayley had spoken about religion and science, and he allegedly said the idea that there was a Supreme Being was “preposterous,” which Bayley subsequently denied he had uttered.

The most serious threat to the survival of Victoria Park came in 1922, when it was announced that Winnipeg Hydro had approached city council to allow at least half of the park at the foot of Rupert Avenue be devoted to a standby plant. The plant would supply the city with power for its streetlights and waterworks system, and supply commercial establishments with electricity in the event of a Winnipeg Hydro power interruption.

At the time, the city-owned utility operated a hydro-electric generating station at Point du Bois on the Winnipeg River. A year earlier, a severe summer storm had damaged power lines from Pointe du Bois, blacking out hydro customers for 24 hours. The power interruption convinced the public utility there was a need for a standby plant.

The Winnipeg Electric Railway Company, which operated the city’s streetcars, already maintained a standby plant in the city. The private-sector company built Winnipeg’s first source of hydro-electric power at Pinawa, which opened in 1906.

The city’s public utilities commission subsequently recommended that the park be used as the site for the standby plant.

When informed of strong public opposition to the plant, J.G. Glassco, the head of city hydro, replied: “There is no intention whatever on the part of the hydro to adopt an autocratic attitude in regard to Victoria park. We desire to negotiate with the parks board in a perfectly reasonable way. The park, of course, is an ideal situation for a stand-by steam heating plant, if eventually decided on” (Winnipeg Tribune, July 22, 1922).

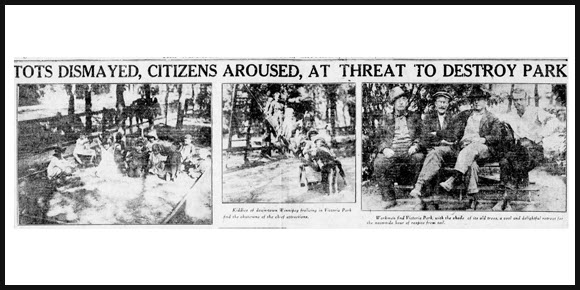

Glassco said he doubted that the park had been greatly used since the erection of the high pressure plant (James Avenue Pumping Station in 1907) on a portion of the park’s land, which was an obvious self-serving falsehood. In reality, the park had been popular for decades, attracting working-class people of all ages. On the other hand, the city’s elite went to suburban parks, such as Kildonan and Assiniboine.

On August 1, a Tribune article stated, “Victoria park still breathes.”

The public utilities committee’s recommendation to allow the Winnipeg Hydro standby plant to be built in the park was referred back to the committee by city council without discussion, which gave the park at least a temporary reprieve.

Council had received a letter from R. McKay, who resided at 97 Pacific Ave., offering land he owned in order to save the park.

“I offer to sell to the city for the purposes of a standby hydro plant lots in blocks Nos. 16 and 17 immediately opposite the park, and having a frontage of 132 feet on Pacific ave., and a like frontage on Alexander ave., at a price and terms to be determined by arbitrators.”

This letter was forwarded to the public utilities committee.

In fact, the committee received another letter sent to city council by Arni Eggertson, offering a site for the stand-by plant on Osborne Street, between Dudley and Lorette avenues and the Red River.

Yet, the committee was still considering Victoria Park as the preferred location for the standby plant.

The August 1 Manitoba Free Press mentioned that city council would look more favourably upon the hydro request if the standby plant was coupled with a central steam-heating plant.

Glassco had earlier made the same suggestion to the council, saying: “Not only is it (Victoria Park) a suitable location for a stand-by plant for the hydro, but it is admirably situated for a central steam heating plant in case the city intends to go into the matter in the future.”

An August 11 Tribune editorial entitled, Hands Off the Park, claimed the existence of the park was being severely menaced by the misguided proposal.

Mention was made of city council and committee members being scheduled to visit the park to determine the feasibility of its use as a standby plant.

“If the members of the committee find the park what it really is, a necessary breathing spot in a congested area of the city, and quite impossible to replace as a park, will they recommend hands off?” asked the editorial.

According to the editorial, it would be found to be a convenient and satisfactory site for the power plant, but they should also see that it was essential as a playground for children and a refuge for tired working men and women, “the one little open space in a district where an open space is appreciated very deeply indeed.”

The editorial writer questioned the validity of putting the interests of the hydro utility ahead of the people.

“The hydro can find other sites, not quite so convenient or cheap perhaps, but suitable and satisfactory. No other park can be provided to serve the purpose Victoria Park does,” ended the editorial.

(Next week: part 6)