by Bruce Cherney ( part 3 of 3)

All hope of the proposed James Richardson & Sons, Ltd., 16-storey skyscraper proceeding at the northeast corner of Portage and Main ended when the Winnipeg Free Press reported on March 31, 1930, that work had started to fill in the excavation site.

“The thousands of cubic feet of earth taken out last year will be replaced as rapidly as it can be supplied.”

Under the dire economic conditions caused by the onset of the world-wide Great Depression, this was ultimately the only outcome that could be expected.

An unnamed real estate agent told a Free Press reporter that there were too many antiquated buildings in the city (published January 11, 1930).

“That is one good result which would accrue to Winnipeg if the James Richardson building had gone ahead,” he said. “It would have made owners of old office buildings located on central sites pull them down and erect modern structures to compete with the class of building Mr. Richardson has in mind.”

On May 14, an article in the Winnipeg Tribune reported Winnipeg Mayor Ralph Webb was proposing that the site be turned into a public open space similar to Trafalgar Square, Piccadilly Circus or a Place d’Armes.

“This site should be purchased and the time to purchase it is now,” said Webb.

“It should be purchased in conjunction with the owners of surrounding property. Winnipeg is bound to become one of the great centres of the continent and the corner of Portage and Main will become more and more congested as time goes on.

“Negotiations might very well be started at once with the Bank of Montreal, the National railways, the CPR, the owners of the Robinson and McIntyre buildings, the Great West Insurance Co., the Canadian Bank of Commerce, the Grain exchange and James Richardson & Sons looking to the raising of a handsome fund for purchase of the property.”

If the Richardsons decided to later construct a skyscraper, Webb proposed that the building be erected on the east side of Rorie Street.

He said if a building did eventually occupy the northeast corner of Portage and Main, an opportunity would be lost forever for “open breathing space.”

While the mayor may have been optimistic about the city’s future economic prospects, the Great Depression made sure the economy remained in the doldrums. Nothing was done to enhance the corner for a number of years and what did come was far from the skyscraper as originally envisioned by James Richardson.

City’s Finest Service Station at City’s Busiest Corner, proclaimed a headline in the June 28, 1934, Winnipeg Tribune.

The accompanying article noted that the one-storey garage opened that day and was owned by one of James A. Richardson’s companies.

R.E. Davies, the manager of the new Lombard Service Station and Garage, said the facility offered gasoline, oil changes, washing, parking, battery care, motor repairs, and brake and tire service.

“Entered by approachong on Portage avenue east and Rorie street, the station has brought the beauty of a building of delightful English architecture (the garage actually looked like a quaint English cottage), stretches of green sward and colorful beds of flowers to the centre of the business section.

“Four gleaming chromium pumps are the first indication of business, but behind the attractive exterior is an installation of the latest servicing devices, in charge of an experienced staff capable of handling motor cars of every manufacture.”

The service station’s gardens were designed and laid out by J. Young, the gardener to James Richardson.

The outdoor advertising stands and signs were the work of Ruddy-Kester, Ltd.

According to the article, the station was illuminated at night by 6,000-watt floodlights.

The new garage was a link in the Ontario-based McColl-Frontenac Oil Company’s Red Indian (a name that wouldn’t be tolerated today) chain of stations that stretched across Canada, selling both oil and gasoline. In 1941, the Canadian company was acquired by the Texas Company and rebranded as Texaco. In 1989, Texaco Canada was acquired by Imperial Oil and all stations began carrying the Esso name.

The filling station was moved to the corner of Arlington and Ellice in 1944 and the northeast corner of Portage and Main was used as a parking lot for over two decades.

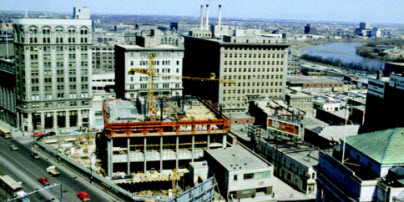

Forty years after the original skyscraper was announced, the Richardson Building was finally completed in 1969. The newer version of the firm’s skyscraper rose to a height of 34 storeys, more than twice as many floors than the 1929 design.

The failure to build the unique Art Deco skyscraper is a “what might have been” in Winnipeg’s history. The corner of Portage and Main would now look significantly different, if not for the onset of the Great Depression, which put an end to the proposed 16-storey building at the iconic corner.

On the other hand, the economic downturn did contribute to saving nearly 150 heritage buildings in the Exchange District (the financial stagnation that started in 1913 and continued for years after the First World War was another contributing factor), as money wasn’t available to demolish them to make way for new construction.

Today, the collection of downtown buildings is one of the few remaining extensive examples of historically significant early-20th-century commercial architecture in North America. On September 27, 1997, the Winnipeg Exchange District was declared a National Historic Site.

“It’s perhaps symbolic that the intersection that most represented Winnipeg saw no major development for more than half a century after the end of World War 1,” wrote Russ Gourluck in his book, Going Downtown: A History of Winnipeg’s Portage Avenue. “It wasn’t until the opening of the Richardson building in 1969 that the intersection began a series of developments that resulted in the renewal of three of its four corners.”

The corner that was not part of the renewal is the site of the Bank of Montreal Building. The neo-classical building, resembling a Roman temple at the southeast corner of Portage and Main, survived because it was both a magnificent structure, as well as a symbol of the city’s earlier economic prosperity that ended just as its construction was completed in 1913. Its survival was further ensured when the Bank of Montreal marked its centennial in 1975 with a major renovation of the building at a cost of $2.4 million — nearly twice the amount it cost to build the bank 62 years earlier.

The Richardson Building was followed by the Trizec/Commodity Exchange Tower on the southwest corner of Portage and Main, and the TD Centre at the northwest corner of the intersection.