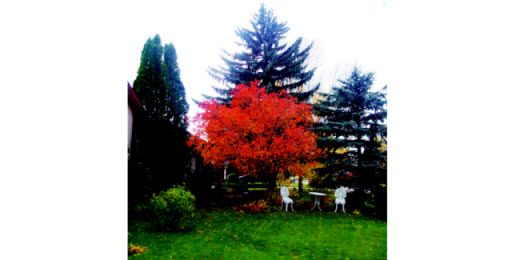

It’s the beauty season in Winnipeg, the time when heads are turned by every pretty falling leaf in its dress of red or gold and cameras can’t help but snap. But how does this magic happen?

While it may seem to us that leaves are gaining colour, the truth is that they are losing it. As the days become shorter and cooler, chlorophyll, responsible for all those vivid greens, begins to break down. This is brought on by a reduction in the delivery of nourishment to the leaves due to the corky layer of cells, called the abscission layer, that begins to build between the leaf stem and the branch, a process designed to separate the leaf from the tree.

In the normal cycle of life, the release of leaves allows the tree to rest during the cold dark days ahead. The leaf lands on the earth filled with much of the food manufactured over summer and breaks down over winter and adds nourishment to the tree once again in the spring.

As the abscission layer blocks the flow of carbohydrates to the leaf, chlorophyll begins to fail. Now the always-present carotenoids, the orange pigments, and xanthophylls, the yellow pigments, can be seen.

Anthocyanins, responsible for the red and purple pigments, continue to be manufactured from the sugars still in the leaf. Eventually, they too will fade and all that will be left are the brown tannins, which may remain throughout part of the winter, but will eventually break down with the rest of the leaf.

The worms and insects perform the first duty, breaking down the organic material to tiny pieces and thus exposing more surfaces to the next step in the deconstruction process for the fungus (moulds) and bacteria to feed and grow upon.

What is left as it all returns to the earth is quite valuable. A single shade tree will shed $50 worth of plant food — as humus — a year. Weight for weight, tree leaves contain twice as many nutrients as manure.

Forests produce one pound of dead leaves and wood per square yard every season. A forest the size of a football field produces 3.2 tons of organics a year. This is a good thing. Leaf mould can hold anywhere from three to 500 times its weight in water.

You may be wondering why some autumns are more colourful than others or why your amur maple is a dull orange, while that of your neighbour is a blazing red. The answer lies in the amount of light, the temperature and the moisture levels in the soil that are available to the plant.

The best autumn show occurs after reasonably rainy summer followed by long, dry, warm days and cool nights in fall. If frost occurs too early, the anthocyanins are unable to develop so the reds and purples won’t occur. Summer drought can cause leaves to begin to drop before their colour develops. Brilliant reds will develop only if the Amur maple is in the sunlight — maybe yours is more in the shade.

As for evergreens, they also lose some chlorophyll in fall and winter. You will notice that their needles turn from bright greens to darker, duller hues, some almost black in the winter. Yet, these “leaves” do not completely shut down in winter. A waxy coating and a kind of internal antifreeze allows them to retain some moisture so they can get through the winter, continuing to expire moisture and oxygen, even on the coldest days.

Yet, evergreens do lose their leaves over time and grow some new ones each spring. Spruce needles live about six years. Juniper and Douglas fir needles last for 10 or more years, while bristlecone pine needles can persist up to 30 years. Cedars shed their old leaves in the fall. Spruce trees lose theirs mostly in the spring and throughout the summer.

In our part of the country, autumn is often brief.

Enjoy these lovely days.