by Bruce Cherney (part 3)

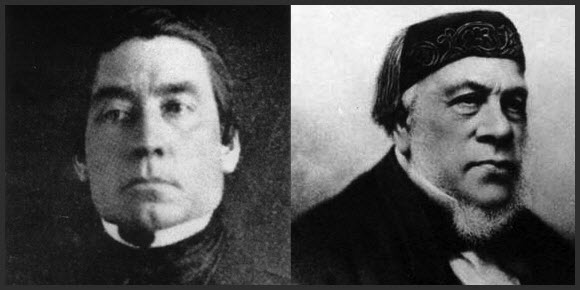

The February 1847 Red River Settlement petition was carried to London by James Sinclair, who handed it over to Alexander Kennedy Isbister, a barrister originally born in 1822 at Cumberland House (Saskatchewan) in Rupert’s Land. The petition, written on behalf of the settlement’s Métis residents, charged the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC, or simply the Company) with maladministration and denying “native” people of the region their right to carry their furs or other property out of the country to the best market. Isbister took the petition to the colonial secretary.

The rumblings in Assiniboia created a stir in England, with some major newspapers giving their support to the Red River residents. The British Colonial Office did heed the criticism levelled against the HBC and ordered an investigation into the complaints. The problem was that the investigation became heavily influenced by the HBC.

When the Colonial Office conducted the investigation into the accusations, the governor of the HBC, Sir John Pelly, refused to accept that Red River residents, including the Métis, who were born in the country, were “natives” and as such enjoyed aboriginal rights.

No party could supercede the HBC rights under the terms of its charter, Pelly asserted, which was the argument accepted by Earl Grey of the Colonial Office, who flatly told Isbister that the charter, giving the HBC exclusive trading rights in Rupert’s Land, could not be challenged.

Earl Grey only acknowledged the residents’ rights as British subjects, adding that the Métis didn’t possess any uniqueness under the law.

In effect, the HBC’s trade monopoly was reinforced by the Colonial Office.

In a spirit of vindictiveness for having signed the petition outlining the complaints against the HBC monopoly, Red River merchant Sinclair was notified by District of Assiniboia Governor Alexander Christie that Company ships would no longer bring consignments of his goods to York Factory.

In another vindictive act, the HBC hierarchy had Father Georges-Antoine Belcourt, who wrote the petition for the Métis that was sent to England, arrested on trumped-up charges. He was submitted to “a course of questions as insolent as they were unfounded.” Despite the efforts of the Company, the priest was innocent of all the allegations made against him.

Still, at the request of Rupert’s Land Governor Sir George Simpson, the Archbishop of Quebec recalled Father Belcourt from Red River. Simpson later regreted his request and asked for Father Belcourt’s return to Red River, but the priest refused to make the move. Instead, he opted to establish a mission just across the border at Pembina in U.S. territory.

The HBC’s heavy-handed actions to curtail trading with the Americans, especially with Norman Kittson at Pembina, set the stage for the events of May 17, 1849, which brought the free trade debate to a head.

In the spring of 1849, Alexander Ross in his book, The Red River Settlement, wrote that Pierre Guillaume Sayer and three men named McGillis, Laronde and Goullé had been arrested for illicitly trading furs with Indigenous people. It was alleged that accepting furs from Indigenous people in exchange for goods contravened the rules and regulations of the Company’s charter, which stated: “That the Hudson’s Bay Company shall have the sole and exclusive trade and commerce of all the territories within Rupert’s Land.”

Sayer was imprisoned and then released on bail, while the other three were not imprisoned, but had to provide bail.

Only in one previous instance had anyone been deprived of their liberty for meddling in the fur trade, according to Ross, “during the whole quarter of a century in which the Company’s officer presided over the affairs of the colony.” Up this point, threats and confiscation of furs were the actions taken by the Company.

Major William Caldwell — judged to be incompetent as the governor of Assiniboia by Ross and many others in the settlement — instituted the new reign of strict enforcement of the HBC charter.

“Had his Excellency, however, issued an official notice, giving people timely warning beforehand that they were to be so dealt with, the Major, as well as Recorder Thom, might have escaped the odium cast upon them in the present instance, nor would they have been taught this severe lesson of humility, nor the public peace have been disturbed as it was,” explained Ross.

“Hudson’s Bay Company versus Sayer” was to be judged in the General Quarterly Court, which consisted of Caldwell as president, Recorder Adam Thom, and councillors and justices of the peace Alexander Ross, John Bunn and Cuthbert Grant, who was named the “Warden of the Plains” by the HBC and was noted as being a loyal Company employee.

Prior to the trial, rumours began to spread throughout Red River that a party hostile to the arrests was poised to keep a close watch over the court proceedings and intervene if the cases didn’t turn out to their satisfaction.

It also didn’t help that the trial was taking place on Ascension Day, a holy occasion for the Catholic portion of the settlement’s population, which happened to be in the majority.

What would evolve into an angry mob seeking justice for Sayer gathered at St. Boniface Cathedral for the Ascension Day service at 8 a.m., an hour earlier than was the custom.

“About 9 o’clock in the morning of that day, the French Canadians, as well as half-breeds began to move from all quarters, so that the banks of the river, above and below the fort (Upper Fort Garry), were literally crowded with armed men, moving to and fro in wild agitation, having all the marks of a seditious movement, or rather a revolutionary movement,” according to Ross.

The protesters were organized by Louis Riel, Sr., the father of the Métis leader of the 1869-70 resistance, who was also named Louis Riel.

Some of the protestors came from as far away as White Horse Plain, where Sayer lived.

According to Peter Garrioch’s journal for 1843-49, leading figures of the community met at James Sinclair’s house, where a paper was drawn demanding an end to the court proceedings until they heard from the British government. The protestors believed the government would rule in their favour on their right to hunt and trade amongst themselves and order the HBC to desist in its enforcement of its fur trade charter.

Ross said he watched from the door of his house at Colony Gardens while the mob assembled. A deputation of ringleaders (Sinclair and others) came to Ross and told him they would be resisting the proceedings at the courthouse.

“My friends,” he told them, “you are acting under false impressions. Beware of disturbing the peace!”

He said the 6th (a British military force sent in 1846) had left the settlement (in 1848), but warned that another military contingent could be sent, if the peace was disrupted.

It should be noted that Ross, although well respected in the settlement, was not a proponent of free trade, believing it would be ruinous for Rupert’s Land. Ross felt that the fight for free trade could have been contained, if it weren’t for the oppressive racism of Thom and the incompetence of Caldwell.

After his warning, Ross walked with the deputation to the fort where the trial was being held.

“The object of the mob was to resist the infliction of any punishment, whether of fine or imprisonment, on the offenders and their anger was provoked by a report that the Major was to have his pensioners under arms on the day of the trial to repel force by force,” according to Ross.

Wisely, Caldwell withdrew this threat. Ross wrote that “the Major dispensed with his usual guard of honour (pensioners), and walked to the courthouse like another private gentleman.”

As the business of the court got underway, Ross said 377 guns were reported in the arms of the residents and others were armed with missiles of every description.

Sayer was summoned to appear at 11 o’clock as the first defendant on the docket, but didn’t answer the call. Sheriff Ross was sent to find the defendant, who was alleged to be near at hand, although protected by the mob. His name was called a second time at one o’clock, but again there was no response.

James Sinclair, Peter Garrioch and Francois Bruneau and eight others appeared as the delegates representing the interests of Sayer.

James Sinclair handed a paper to the court and Thom asked him in what capacity he and the others appeared. He answered, “As delegates of the people.”

To the chagrin of the “delegates,” the recorder told them that they could not appear in a court in that capacity and proceeded to lecture them on the nuances of the law (Aspects of the Legal History of Manitoba, by E.K. Williams, MHS Transactions, 1947-48 season).

In his history of Manitoba, Frank Schofield wrote that Thom “was dogmatic and prone to make long dissertations on the law as he understood it, facts which did not commend him to the practical British-born colonists, and he did not speak French, a serious disability in the eyes of more than half the people in the settlement ... To the colonists Mr. Thom sometimes appeared to act as lawyer and judge, and this did not meet with their approval.”

Actually, Thom could speak and understand some French — how much is not exactly clear. After all, he had been a lawyer in Lower Canada (today’s Quebec). A knowledge of French was also a condition of his employment demanded by HBC Governor Sir George Simpson. Thom told Simpson that he was able to converse in French and so he was hired.

But while in Red River, he simply refused for years to speak the language or allow it official status in his court.

(Next week: part 4)