A recent drive from Vancouver to Whistler on a rare sunny day took my breath away for two reasons: my sister’s driving and the extraordinary beauty of the landscape.

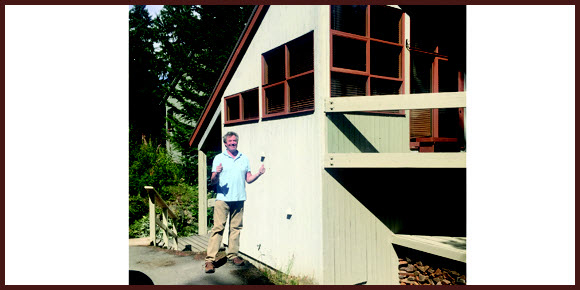

My reason to be in B.C. was to help my sister renovate her aging ski chalet in Whistler. She and her husband made a savvy move back in the mid-’70s by purchasing land in the then fledgling ski resort. Before the decade ended, they had erected a modest three-level chalet constructed of solid eight-by-18-inch fir beams and rugged vertical siding.

Considering the amount of moisture in the form of snow and rain the Whistler area receives each year, the old chalet has stood up well to the elements during its 40-year lifetime.

Our original DIY plan was to remove the kitchen cabinets and countertops, tear up the linoleum and cart the stove and fridge to a nearby recycling depot. But this idea was scuttled when we discovered that the oak trimmed, white melamine cabinets and the vivid blue Flo Form countertops were in very good condition. Moreover, the linoleum remained as flat and unmarred as the day it was laid.

And the stove, though one burner was not working, was one of those dependable older appliances that was manufactured before “built-in obsolescence” became an industry standard. Ditto for the ancient fridge, which had been running almost continuously for two score years.

As my sister wanted to retain as much of the chalet’s traditional charm as possible, we decided to nix the kitchen reno. Instead, we made a list of niggling items that had been on her repair list for many years but had never gotten done, as major jobs are bumped to the top of a never-ending fix-it agenda.

First up was the single-lever kitchen faucet that had worked itself loose from the Flo Form countertop, suggesting that a slow leak in the faucet had rotted the particle board substrate to the point where it had no structural integrity. In fact, it was this problem that had led to a discussion of renovating the entire kitchen in the first place.

However, after I crawled underneath the kitchen cabinet with a flashlight and closely inspected the area where the tap’s stem poked through the particle board from above, I discovered that the faucet, not the countertop, was at fault. It was designed to be installed in a modern stone countertop with a thickness of about 1 1/4 inches, compared to three-quarters of an inch for Formica tops.

My sister said the single-hole faucet had been installed about a year earlier, a replacement for a worn out three-hole model. To accommodate the new tap, the plumber drilled a 1 1/2-inch hole into the particle board through which the faucet’s stem was designed to fit snugly.

I believe a problem arose when the plumber tightened the single nut designed to hold the faucet in place. In theory, this action forces the stem to expand in the hole and thereby lock the entire assembly into position. In reality, this type of “friction fit” fastening system is unreliable, even in some stone countertops. Moreover, it is extremely difficult to tighten the nut further because it is hidden behind the sink. My bet was my sister’s faucet was never properly secured because it was mounted in particle board, not stone.

I made a vain attempt to save the faucet by removing the sink and beefing up the tap’s stem hole in the particle board by adding a layer on the underside of three-quarter-inch plywood. This proved futile as the nut responsible for holding the tap in position had been reefed as tightly as possible, likely by the plumber trying to get the assembly to seat solidly.

While I wasted more time dickering with the faucet, my sister went in search of a replacement. Though Whistler is blessed with a number of brand name DIY stores, she was unable to find a new tap with a bracket-type attachment. Cheap, friction fit faucets seemed to be in vogue.

In desperation, she located a plumbing store for pros. The salesman sold her a Moen faucet that could be mounted with a bracket and came with a lifetime warranty. It also included a socket wrench that made it easy to tighten the bracket nut, even when the little stinker was obscured by the sink.

After striking the first niggling item off of our DIY list, my sister decided we should ditch the original agenda and embark on something entirely unexpected — painting some weathered beams that were about 20 feet above the unlevel ground below. As she owned a six-foot step ladder, a call was made to a tool rental agency in Whistler for an extension ladder.

Early next morning the “Ladder from Hell,” as it became known, was delivered by a six-foot-four giant, full of muscle and from way Down Under (there are a lot of Aussies working in Whistler). He lifted the ladder out of the back of his truck with a single hand and passed it to me.

I noted that it was not the extension ladder I had ordered. It was, in fact, a 14-foot step ladder made out of extra thick aluminum, fitted with cast iron feet and capped with a cast iron step. Another thing I noted was that I required two hands with which to carry it.

I felt my sciatica flare up as I lugged the thing toward the chalet. For her age, my sister is a strong and fit individual. But between the two of us, we could not heft the Lucifer of ladders into position. A call for help went out to my sister’s son-in-law, who lives in Whistler. Aided by his youthful enthusiasm and strength, we managed to place the ladder, more or less, where it was required, cracking only one smallish window in the process.

The DIY tip here is to hire a pro to paint anything higher than eight feet from the ground. Also, never attempt to carry a roller and a flimsy paint tray up a 14-foot ladder unless you have lots of paint and are not concerned by splash back on windows and your relatives.