by Bruce Cherney (part 4 of 4)

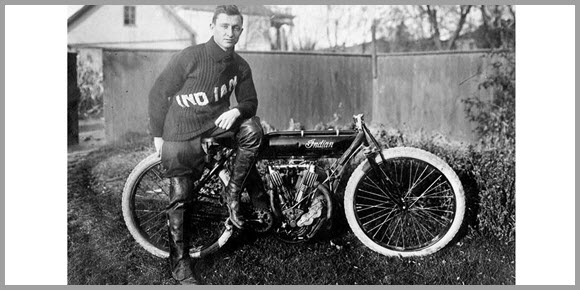

According to A.C. Emmett, who was the secretary of the Winnipeg Automobile Club and a Manitoba Free Press editor, when the first lap was covered in 59.8 seconds, the expectation was that “Wild” Joe Baribeau on his V-twin Indian motorcycle would keep under a minute-a-mile pace for each lap over the entire 100 miles and establish a new world record on October 14, 1911, at the Kirkfield Park dirt race track.

“From the second to eighth lap, however, Joe did not succeed in getting under the minute mark ... Thirty miles were reeled off in 30 minutes 3 3-8 seconds (the use of hyphens was how the newspapers of the day reported fractions) and during the next ten miles he further improved his position until the official announcement gave the time as 40 minutes 1 4-5 seconds (early newspapers used hyphens to indicate fractions) or a shade less than 2 seconds over a mile a minute for the distance” (Free Press, October 16, 1911).

Baribeau kept improving his pace and by the 59th lap his time was 58 minutes 2/3rds seconds.

On the 71st lap, Baribeau signalled to the sidelines that he was running out of gas. Refueling was a tricky procedure, involving another motorcycle rider. W. “Bill” Pelham, who “took a gasoline funnel (can) fitted with a closed-in top and a thumb release tap, and after filling this with gasoline mounted his wheel and rode around the track until Baribeau caught up, and the big funnel changed hands while both riders were flying around the track at close to 55 miles an hour. This stunt was so well arranged and carried out that Baribeau only lost six seconds from his mile a minute mark.”

By the 75th lap, Baribeau was again under a mile a minute. On the 81st lap, Baribeau signalled for more lubricating oil for his motorcycle’s engine. The procedure set him back by 47 seconds.

Still, he was able to make up more time after adding the oil. With 10 laps to go, he had 12 minutes to complete the 100 miles at an under a mile a minute pace.

“This feat was accomplished without a hitch, and amid a scene of the greatest enthusiasm the 100 miles was completed and a new world’s record created.”

After the record-setting run, Baribeau’s “frozen” hands had to be pried off the handlebars of his motorcycle. His legs were so stiff he could not walk, and he was so exhausted that he could not speak. Baribeau was carried to a waiting car and driven downtown.

At the track, his enthusiastic fans passed the hat and collected $60 for an engraved gold medal honouring his accomplishment. He also received hundreds of congratulatory messages.

Baribeau promised after setting the world record that he would “immediately make an attempt to regain it,” if someone else surpassed his time.

It wasn’t the first time that Baribeau had taken a stab at the record. During the Winnipeg Automobile Club’s meet at Kirkfield Park a few days earlier, he rode in complete darkness for the last 15 miles of that attempt.

“The timekeepers had to be supplied with light in order to make it possible to see their watches and all the view obtained of Baribeau was a black blur that flitted by to the accompaniment of a flash of flame from the open exhaust of the engine,” reported the Free Press on October 11.

“There is not the slightest doubt but that the little western wonder could go out and establish new figures if he started and finished in daylight and made provision to carry a supply of lubricating oil sufficient for the trip.”

Without a handy supply of oil, Baribeau lost over nine minutes when the machine’s engine had to be topped up with oil during the race.

Emmett’s advice proved to be a hinderance during Baribeau’s second attempt for a world record on October 14. Baribeau found that the oil reservoir contained in a rear rack was so heavy that it caused his motorcycle to dangerously swerve in the corners, so he stopped after one lap to drop it off.

It was reported that the track was so dark during his first attempt at the record that the rider only narrowly escaped colliding with the fence on several occasions.

Despite the conditions, Baribeau did set a new Canadian record for 100 miles with a time of one hour, 50 minutes and 25.8 seconds.

At the Kirkfield track in 1911, he set a record for the mile at 56 seconds. His time for five miles aboard the two-cylinder Indian was four minutes and 48 seconds. On a single-cylinder Triumph motorcycle, his time was five minutes and 25 seconds.

Baribeau was born in 1899 in Kenora and came to Winnipeg in 1910. He left Winnipeg in December 1911 for Springfield, Massachusets, to take up a position with the Hendee Manufacturing Company, which made the Indian motorcycle.

Before leaving, he donated a silver cup to the Winnipeg Motor-Cycle Club for a 50-mile championship race that was confined to members of the club (Tribune, December 27, 1911).

When Hendee opened a new assembly plant on Mercer Street in Toronto, Baribeau moved to that city in 1912. He became a professional racer for the factory team that competed across North America.

“It became common for the ‘peerless’ Joe to clean up in every class he entered, and he became wildly popular with the crowds even if the winner was a foregone conclusion,” according to a Canadian Motorcycle Hall of Fame article about Baribeau. “He was a born promoter, racing against an airplane at CNE Stadium in Toronto and winning. He was also musical, playing mandolin in orchestras in Toronto and Winnipeg.”

In 1913, he married Winnipegger Daisy Summers Steeple. They had six children.

He left Toronto in 1914 when the First World War started, returning to live in Winnipeg. He participated that year in the Dominion (Canadian) Motorcycle Championship, hosted by the Manitoba Motorcycle Club, at the Kirkfield Park track, winning the 10-mile professional rolling start championship aboard an Indian motorcycle.

This was the last time that the track was used for motorcycle racing. Automobile racing was held for the last time at the track on Canada Day (July 1) 1914. All the auto club’s and motorcycle club’s racing events in 1915 were held at the Winnipeg Industrial Exhibition track in the North End.

Upon retiring from motorcycle racing in 1915, Baribeau opened an auto repair shop in Winnipeg.

Baribeau, the record-setting motorcycle racer, died in Winnipeg on October 6, 1950, at age 61, and is buried in Assiniboine Memorial Park Cemetery (now Chapel Lawn Memorial Gardens).

Oldfield died on October 4, 1946, of a cerebral hemorrhage. He was buried in the Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California. It was not the end he would have chosen, according to an American Heritage article by Richard F. Snow. “If I go,” he had once said, “I want it to be in the Blitzen Benz, or a faster car if they ever build one, with my foot holding the throttle wide open. I want the grandstand to be crowded and the band playing the latest rag. I want them all to say, as they file out the gate, ‘Well, old Barney — he was goin’ some!’”

During the First World War there was one attempt made to re-open the track. In the August 1, 1917, Tribune appeared an article headlined, Race to Save Kirkfield Park Track Charter, it was reported that the Manitoba Jockey Club staged a meet of just two races.

“No work was done on the track, which was in poor condition because of it not having been used since the (First World) war started.”

Only 50 spectators showed up to watch the horsing racing. The meet to save the Kirkfield Park track was a disaster and the race course’s days ended with a whimper.

After the war, the Canadian Aircraft Company operated from the southern section of the Kirkfield Park property off Portage Avenue, which began to be referred to as the St. Charles Aerodrome. It was from this makeshift airfield that the first northern charter passenger flight was made to The Pas in 1919.

Meanwhile, the race track off Ness Avenue was simply abandoned to the whims of nature and the passage of time until there was yet another attempt to reintroduce horse racing at Kirkfield Park.

The September 1, 1925, Free Press, contained an announcement by the Winnipeg Driving Club (a harness-racing club that also hosted horse racing) that it was proposing to move its operations from River Park to the Kirkfield Park race track in 1926.

“The Kirkfield Park track, which was built by the late R.J. “Rod” MacKenzie, is almost entirely constructed of imported material (from Virginia),” said WDC president W. Halpenny, “with tile drainage over the full circumference and large concrete outlets at (the) extreme ends of the track. In view of the high-grade materials originally used in its construction, the track itself will be first-class condition with little work.”

Halpenny said plans were being drawn up for a 6,000-seat grandstand, club house and stables for 200 thoroughbreds. A steeplechase course was also planned.

He said the WDC was willing to spend $125,000 for the erection of stables and other accommodations at the Kirkfield Park track.

“Mr. (Rod) Mackenzie ... intended it to be a landmark to the province, and had it not been for the Great War (First World War) interfering, the track would have undoubtedly received wide recognition long before this,” he added.

Halpenny said all the buildings on the site would be torn down to make way for new construction activity.

Whatever the club’s intentions, another article four years later indicated the Kirkfield track was never used by the WDC. The June 3, 1929, Free Press reported that a fire had leveled the “Rod MacKenzie stables at the old, discarded Kirkfield Park race track ...”

The key word in the article is

“discarded.”

In 1926, the provincial government could not arrive at an agreement on splitting the number of race days between Polo Park, Whittier Park and Kirkfield Park, nor did it believe that a third horse racing venue needed to be added in the vicinity of the city, despite the WDC and the Rural Municipal of Assiniboia, where Kirkfield Park was located, pushing for its approval.

Furthermore, the September 15, 1925, Tribune reported that H.A. Argue, a director of the WDC, claimed the club’s charter did not permit holding races at Kirkfield Park, since it was beyond the three-mile limit from the city specified in the WDC charter.

“I want to make these facts clear to the public,” said Argue, “because I am convinced that the Winnipeg Driving Club in the suggested Lechtzier deal (he had an option on the Kirkfield track) is proposing to lead itself to a promotion proposition which is not in the best interests of the sport and the city generally.”

Actually, the three-mile limit had been imposed by the 1910 Miller Act, a federal bill governing horse-race betting that was still in effect.

In addition, Clause 3 stated: “In any city, town, village or rural municipality horse-racing meetings or horse-racing may be held at one but not more than one race-track in each calendar year.”

According to Clause 4: “No horse racing meeting or horse racing shall be for a longer period than three consecutive days, Sundays excluded, except in a city of more than 10,000 population.”

Also under the act, a total of 21 days had to elapse between seven-day meets, a provision that wasn’t amended until 1936.

Since St. Boniface was then a separate city, Whittier Park, which opened in 1924 and closed in 1943, could host race days under the Miller Act. Polo Park in St. James was within the three-mile limit of Winnipeg’s western boundary and thus was designated as the city’s sole horse racing track allowed under the provisions of the act.

River Park horse racing ended when the WDC abandoned its lease at the track and Polo Park, built under the auspices of the Winnipeg Jockey Club and the charter of St. Vital Agricultural Society, opened in 1925. The Polo Park track and facilities were torn down in 1956 to make way for the shopping centre that is still in operation. The last sanctioned summer races at River Park were held in September 1925.

The events of 1925 and 1926 marked the end of any further attempt to resurrect Kirkfield Park as a racing facility. Instead, the property became the site for a suburban development.