by Bruce Cherney (part 2)

During the great land boom of 1881-82 in Winnipeg, there were unethical rascals, who made a career of duping the unsuspecting by way of fraudulent real estate transactions. As a result, Eastern Canadian newspapers (many of those delving into the speculative land market were new arrivals from Ontario with a smattering from Quebec) began to warn the unwary about the potential of being swindled. In addition, the newspapers issued a caution about the “vile lust of gold” that overpowered morals and annihilated reason.

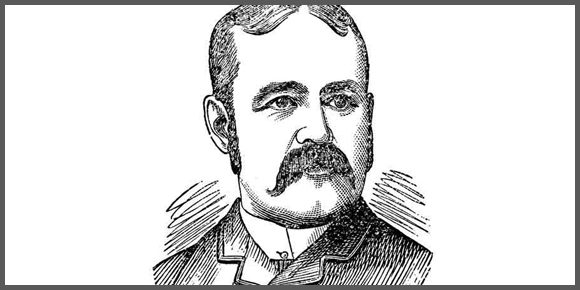

As a self-described leading promoter of the boom, James “Jim” Coolican was after the fact noted disparagingly as being an “unscrupulous” land speculator. Coolican made a fortune by selling Winnipeg, Manitoba, B.C. and the North-West Territories (this was a time before Saskatchewan and Alberta were created) properties — often in fictional towns created by his fertile imagination — at unsustainable prices.

Dr. George Bryce in his History of Manitoba (1882) described Coolican as “eloquent, aggressive, unscrupulous, and by advertising his sales without commonplace things called facts, undertook to ‘stampede’ — to use the language of the plains — the Winnipeg community.”

To be fair to Coolican, similar to so many others, he was simply caught up in the euphoric atmosphere of the land boom and the prospect of attaining sudden wealth at the stroke of the auctioneer’s gavel. Still, like the city’s other top auctioneers, he played a major role in promoting the boom until its bitter end.

On winter mornings when Coolican, who was known as the “Real Estate King,” walked to his auction house — The Exchange, which stood at the northwest corner of Portage and Main (it was often referred to as “Coolican’s Corner”) — he wore a $5,000 seal-skin coat and matching hat. His fingers were said to have sparkled with diamond rings of even greater cost. Other accounts noted that he carried a selection of valuable diamonds in a coat pocket.

Following a day of lot sales valued in the thousands of dollars, it was further claimed that Coolican was prone to bathe in a tub filled with champagne.

But bathing in champagne was merely an anecdote repeated by people to express the exuberance of attaining quick wealth. What is known about Coolican is that he did buy case upon case of champagne, but it was for drinking, not bathing.

In reality, it was Captain J.S. Vivian, who is actually known to have taken a champagne bath. He was a monocled Englishman who came to Brandon in the summer of 1881 with £1,000 (at the time, approximately $5,000) in his pocket. Vivian bought up a 160-acre homestead in the Brandon district, which he sold at inflated prices, and by February was said to be worth $400,000. To put this amount into perspective, an 1881 dollar is worth about US $23 today. But unlike today, the Canadian and American dollar was roughly at par in 1881 and 1882.

Vivian had bought so much champagne to celebrate his success that he wasn’t able to drink it all, even with the help of his friends, so he invited them to watch him splash about in a champagne-filled bathtub. His champagne dip was alleged to have cost him $750.

In another account of the incident by James Scott, the first president of the Winnipeg Real Estate Exchange (today’s WinnipegREALTORS®), which was published in the October 11, 1906, Winnipeg Tribune, wrote that Vivian cleared a profit of $50,000 selling Brandon lots and then came back to Winnipeg and took the champagne bath. “It is said that the hotel keeper, thinking it a shame to waste good wine, had it bottled again.” Scott cited the bath as costing just $200.

The champagne bath marked a new high in extravagance, whether it cost $750 or $200.

Conspicuous extravagance became the norm for the nouveau riche during the great land boom. Sumptuous, exotic meals were offered at the city’s best hotels. Well-heeled customers delightfully gulped down dozens of oysters on the half shell while seated at a hotel dining room table.

Coolican’s obituary announcing his death in Chicago, which appeared in the Manitoba Free Press on April 12, 1902, noted that in The Exchange auction house, “his cheery voice could be heard, sometimes in jest, at most times in earnest, disposing of hundreds of lots in exchange for coin of the realm.”

The auctioneer obviously took great delight in his role in promoting the land speculation fever sweeping the West. His advertisements in the Free Press proclaimed himself as, “The Boom Starter!”

(Next week: part 3)