by Bruce Cherney (part 2)

On September 7, 1619, Jens Munk had found the only natural harbour on the western shore of Hudson Bay at the mouth of the Churchill River, which he aptly named Munkhavn (Munk Haven), which is the site of today’s Churchill, Manitoba, Canada’s only seaport in the Arctic.

Munk claimed the land in the name of the Danish king and called it Nova Dania (New Denmark).

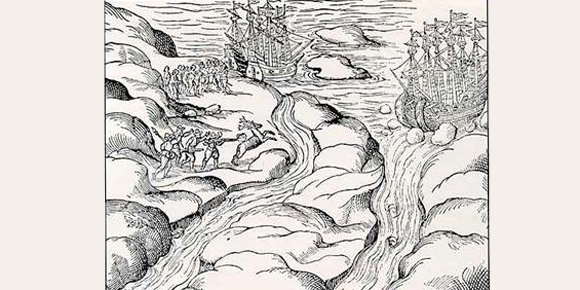

The temperature soon after dropped quickly and ice began to form on Hudson Bay, which forced Munk to make the decision to overwinter. Munk sailed his two ships — The Unicorn, a frigate,and The Lamprey, a sloop — about 10 kilometres down the Churchill River and moored them as close as possible to the west shore at high tide (the river is noted for its tides where it flows into Hudson Bay), making docks with rocks and branches. At low tide, the men were able to walk around the two ships and to the shore.

“This place was recognized by Thorkild Hansen and Peter Seeberg during the Munk Memorial Expedition in the summer of 1964,” wrote Jon Carlsen in Jens Munk’s Search for the North West Passage in 1619-20 and His Wintering at Nova Dania, Churchill, Manitoba. “Hansen and Seeberg found chiselled-out holes in five big stones to which at least the Enhiorningen (The Unicorn) may have been fastened.”

In his diary, Munk wrote that the heavy (six to eight) cannon from the frigate were used at the bottom of the hull to provide stability. The removal of cannon cleared the battery deck of the ship which was then turned into a common room with two fireplaces to help warm the crews of the two ships.

“The signs of the coming winter were everywhere,” wrote Carlsen, using Munk’s diary to outline the crew’s hectic preparations for the coming bitter cold. “Firewood was cut and hauled to the ship. There was still plenty of game to be shot, a welcome relief from the standard diet of salted meat and dry biscuits that had been brought from home.”

On September 12, 1619, a large white bear was noted below the ship, “which was eating some Baluge (Beluga whale) flesh” (actually, Munk mistakenly referred to the mammal as a fish and one had been caught by the crew a day earlier). The bear was shot and eaten, while its fur coat was used by the captain to keep him warm. In his diary, Munk said the polar bear’s meat “agreed very well with them.”

According to Carlsen, Munk was a good motivator of his men, at least while the weather was bearable. The ships’ carpenters built two sheds on shore for storage, for example, to safely store their supply of gunpowder.

But when the cold weather began in earnest, it became evident that Munk and his men were far from adequately prepared — no member of the crew nor Munk had winter attire appropriate for the Arctic climate. On October 4, Munk distributed to the crew every item of clothes, shoes and boots that were available in stores.

“It was also at this time before the ground was covered by snow that Munk became aware that the natives seem to have had a summer camp at this place. Some flat stones were found, according to Munk, arranged in altar-like fashion.

“One night, some weeks later, the guard shot a black animal which turned out to be a dog with its mouth tied together (a sled dog?). Munk wrote that alive it would have been sent back to its owner with gifts, and contact could have been established as a result” (Carlsen).

By October 22, the ice stopped moving and The Unicorn was held fast in its mooring. On November 10, St. Martin’s Eve was celebrated with some grouse making up for the absence of goose.

“Munk noted that the beer was frozen by that date, but the crew were at liberty to drink what they could thaw,” wrote Carlsen. “Christmas was celebrated in an optimistic mood and the Reverend Rasmus Jensen delivered the first Protestant Christmas sermon in Nova Dania. The crew ate grouse and a hare and were given wine and strong beer to drink.”

Munk said the men were “half-drunk” and happy. But the good times would not continue into the New Year. The crew’s living conditions began to deteriorate and they were forced to give up attempting to hunt when extreme frost and snow struck with a vengeance.

The men did comb the snow-covered tundra for frozen cranberries and crowberries, which provided scant nutrition to stave off scurvy, a severe lack of vitamin C. Humans cannot synthetize the vitamin, so it has to obtained from external sources, such as fruits and vegetables. A British Navy surgeon would later discover citrus fruits’ ability to prevent scurvy, earning His Majesty’s sailors the nickname, “limeys,” after the lime juice they drank which was added to their daily ration of rum called grog.

As a result of the disease, Munk and his 64 men suffered joint pains, ulceration and bleeding of gums, tooth loss and extreme exhaustion. Scurvy was one of the diseases which plagued European explorers when they overwintered in less-than-hospitable locations and lacked the indigenous people’s knowledge to prevent the disease. One hundred of Jacques Cartier’s 110 men were sickened by scurvy in 1536, but many of the French explorers were saved by drinking a native concoction of ground coniferous needles and bark (called anneda, probably white cedar) boiled in water.

In some accounts, it was said that Munk’s ships had plenty of herbs and medicines to prevent scurvy, but no one was aware how they were to be used, and so they began to die. But first, scurvy made it impossible for frostbite or the lesions it caused, especially on legs, to heal. The men became lethargic and unable to fend for themselves in the hostile environment. In the overwhelming cold they either succumbed to the below freezing temperature, starved to death or died outright from the effects of scurvy itself. The first death from scurvy among the crew occurred on November 21, 1619.

Munk wrote that the men were “seized with such violent pricking pains in their limbs, as made them look like mere shadows; their arms and legs being quite lame and full of blue spots, as if they had been beaten ...”

Munk said that every man knew they had been stricken by scurvy as it was a common ailment for sailors.

“The 10th of April passed Maurltz Stygge away,” wrote Munk, “my lieutenant, who had long been a sick man, and I took my own linen and wrapped the body as well as I was able to, and it held hard to get a coffin.”

As the crew weakened to a state of ultimate fatigue, they could not bury their dead and corpses piled up among them.

At the beginning of May, Munk wrote: “Erik Hansen Lee, who on the entire trip had worked hard and been of great service, and never displeased anybody nor deserved any punishment, and who had dug many graves for his fellow-mates, had to be left unburied, as their was no one to bury him.”

When the May sun finally warmed the landscape, the dead emerged from the melting snowy blanket that had covered them.

Monk, himself, was barely able to hold his quill and put ink to paper when he wrote in May 22, 1620: “By the Providence of God there came a goose close to the ship, whereof the leg had been shot off three or four days before. This we did seize and cook, whereof we had sustenance for two days.”

The following passage in Munk’s diary illustrates their desperation: “By June 4 there were only four of us left alive, and we just lay there unable to do a thing. Our appetites and digestions were sound, but our teeth were so loose that we could not eat; nor did we have the strength to go down to the hold for more wine. The cook’s boy lay dead beside the berth, while others lay dead in the steerage. Two men were still on shore, simply because they were too weak from the illness to climb back on board. None of us had any sustenance for four days. I could hope for nothing, under the circumstances, but that God would put an end to my misery by taking me to Himself and His Kingdom.”

Munk was surrounded by death when he wrote his “last will,” asking for the finder of his diary to bury him and his crew and take his diary to the Danish king. A few days later just Munk and his dog were among the living aboard the ship.

To Monk’s utter delight, on June 8, after crawling to the deck to escape the stench of decaying bodies, he spied two men on shore and very much alive. They were the two men mentioned earlier by Munk who had left the ship several weeks earlier, but were unable to return until that moment. They were so overjoyed to see their captain on the ship’s deck that they took him in their arms, helped him ashore and built a fire “to refresh his spirits,” although they were also debilitated by scurvy and starvation.

Munk and the other two survivors crawled along the ground eating green shoots which replenished their energy, enabling them to retrieve guns and powder to shoot game and birds. “Hunting, so strengthened them in little time, that they resolved to return to Denmark” (1650 English version of Munk’s journey).

They began to prepare The Lamprey for a return voyage to Europe. Normally, such a ship required a crew of 16, “so it was obvious that Munk and his two men had a superhuman task in front of them,” wrote Carlsen. They managed to get the ship out of its dock at spring tide.

Before they embarked on their homeward journey, on July 16, Munk drilled three holes in The Unicorn: “In order that the water might be in the ship and remain when the ebb was half out so that the ship should always remain firm whatever ice might come,” he wrote.

It was his intention to eventually return and refloat the ship.

On the same day as The Unicorn was purposefully sunk, the three men set sail in The Lamprey for Europe from Churchill.

(Next week: part 3)