by Bruce Cherney (part 4 of 4)

After repeated attempts to force 33 buffalo bought by Charles “Buffalo” Jones from Stony Mountain Penitentiary warden Samuel Bedson onto loading chutes leading to rail freight cars ended in failure, what was described as a miracle occurred.

According to the December 15, 1888, Free Press: “Finally, a tremendous old bull, which had been making trouble all day by breaking away, or hooking the younger cattle, undertook to run the show himself; and where the men had failed he succeeded. He got behind the herd and began making it exceedingly lively for the buffaloes ahead, prodding them, bellowing at them, and driving the laggards forward with vigorous prods of his horns.”

The reporter believed the old bull was attempting to start a stampede in the manner that buffalo had followed since time immemorial.

“When the ‘boss’ had driven them all in and reached the door himself he seemed to be slightly astonished, this was the most extraordinary stampede that he had ever engineered. Tossing his head scornfully, he wheeled about and ran back into the compartment he had just left, and jumped into the next one, clearing a fence ten feet high. Not liking the looks of this he jumped back again and struck out wildly for Stony Mountain.”

The bull was reported to have cleared every obstacle he met until he reached the board fence bounding the west side of the Winnipeg Stockyards (Canadian Pacific Railway’s stockyards at the foot of Logan Avenue), which was 14 feet high. Still, he jumped, “struck it at the top, went through it with a crash, and struck out for home across the prairies, a very much disturbed and agitated buffalo.”

What happened later to this old bull was not reported, but it can be presumed that he made it back to Stony Mountain, where the remainder of the herd was being kept until they could be collected for shipment to Garden City, Kansas. The other buffalo were less fortunate as they were aboard the freight cars and on their way across the international border.

The Grand Forks Plaindealer reported on December 16 that the two carloads of buffalo had arrived in the North Dakota community and the animals were unloaded to feed. The sole juvenile was a lone calf, “and he seemed lost in the crowd of adult buffaloes.”

It was further reported that “one or two of the creatures were killed here,” although the means of their death was not reported. The two rail cars were apparently so overcrowded that at least a quarter of the entire herd was killed during the confinement in the boxcars while being transported to Kansas. The journey south seems to have been a leisurely affair, encompassing at least three weeks.

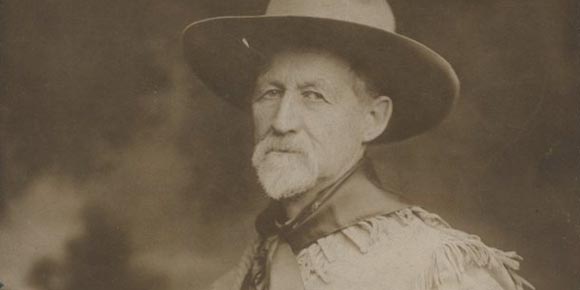

At Kansas City on January 18, 1889, it was Jones’ intention to allow the people of that city to have a glimpse of his newly-acquired herd from Manitoba. On that day, the Abilene (Kansas) Daily Reflector reported the herd was being driven from Union Station to the place arranged to keep them penned in Kansas City until they continued their journey to Jones’ ranch. Caring for the buffalo had been entrusted to Dr. W. F. Carver, a sharpshooter who was reputed in the days when millions of buffalo wandered the plains to have killed more of these animals than any other man — his was a strange selection given his past role in the near-extinction of the beasts. In addition, Carver had been pestering Jones to sell the herd to him so he could use them in a wild west show.

Delving into the realm of fanciful speculation, some may imagine that the beasts had a deep-seated collective memory of Carver’s misdeeds against their kind and set about to exact their revenge. But the real reason for their actions was that they were the spawn of wild animals and as such reacted with instinctive refusal toward any concerted attempt to be confined.

Carver and 16 mounted men were to have herded the animals out of the rail yard to a pen in the centre of the city.

“The first twelve, including one huge animal, which must have weighed fully 8,000 pounds (a gross exaggeration as an adult buffalo male typically weighs around 2,000 pounds — 900 kilograms), left the car (the first of two), ran down the chute arranged, jumped a small raised place and were safely corralled. Then there came a medium-sized two-year-old bull of peculiarly vicious disposition. He ran down the chute at a thundering pace, rushed over the obstruction, made his way with relentless force through the corralled herd, pushed the mounted men aside and started north on the rail track.”

Some men attempted to head the bull off, but then a train whistle sounded and the whole herd bolted and rushed headlong down the tracks toward the Missouri River. People waiting to catch a train were in a panic and sought safety wherever it could be found.

“The sight of a herd of buffalo on the plains was an exciting scene,” reported the Kansas newspaper, “but a buffalo chase in the heart of a great city was something never seen before and perhaps will never be again.”

Carver and W.F. Landers headed off one bull and five smaller animals using clubs.

“One huge animal ... and a patriarch of the herd gave considerable trouble. First Carver would hit him a heavy blow on one side of the head and then as the great brute would turn on him he would jump behind a tree or a telephone pole or any thing convenient.”

Eventually, the beasts were subdued and corralled in a pen on Walnut Street.

An April 19, 1889, Free Press article indicated that “five fine bulls ranging from three to five years of age” of the herd still being held for Jones at Stony Mountain had wandered off.

When it is discovered that the buffalo were missing, Sam McCormack, an employee of Bedson’s, set off in pursuit. “He followed them up night and day, but owing to smoke from prairie fires and high winds which filled their tracks with ashes, he was unable to catch sight of them.”

On April 18, it was reported in a “whirl of excitement” that four large buffalo were wandering at large between High Bluff and Portage. “The buffalo were first seen in Thomas Bell’s meadow, one mile and a half from town quietly feeding, quite unconscious of any danger from the surrounding settlers, but their peaceful rest did not long remain undisturbed, for as soon as observed by some Henderson boys, old veteran buffalo hunters who, no doubt, imagined they were again living within the range of the buffalo haunts, mounted their ponies and gave chase and succeeded in killing one, and when last seen were in close pursuit of the rest.”

Portage Chief of Police Huston telegraphed Bedson that three of the buffalo had been shot and that he had seized one of carcasses, while another had been wounded, but escaped its pursuers by jumping into the Assiniboine River and swimming to the other side.

The community was outraged by the inglorious slaughter and demanded swift retribution. (I have been unable to find information about what happened to the Hendersons following the shooting of the buffalo.)

McCormack left for Portage la Prairie by train to secure the heads, hides and carcasses of the dead animals. The Free Press reported on April 20 that McCormack returned to Winnipeg with the heads and hides of the three dead animals. The meat from the three buffalo was deemed unfit for human consumption, so it was thrown away. The remaining two buffalo, including the wounded one, apparently made their way overland back to Stony Mountain.

Jones only kept the herd for a few years before selling them to Charles Allard and Michael Pablo, who had established a buffalo ranch in Montana. By this time, the herd had been depleted by ill-health — they were infested with Texas cattle lice — to just 26 pure-bred and 18 hybrid animals. Jones’ need to sell was forced upon him when he became heavy-indebted during the financial panic of 1893.

Allard and Pablo already had a small herd of buffalo at their ranch, which included 13 head purchased from a local Native American, Samuel Walking Coyote, for $2,000.

“One decade later Lord Strathcona (Donald Smith) presented 18 buffalo to the Dominion of Canada,” wrote Sheilagh C. Ogilvie in The Park Buffalo, 1979, published by the Calgary-Banff Chapter of the National and Provincial Parks Association of Canada. “Citizens of Winnipeg, after vigorous protests at losing them from the city, were allowed to choose five animals (some accounts say four animals) to be grazed in the city’s Assiniboine Park ...

“The City of Winnipeg boasted a second small herd at River Park. These animals had formed part of the Pablo-Allard herd and had been purchased first by Howard Eaton and then by the Winnipeg Street Railway Company. It seems that they were later transferred from River Park to Assiniboine Park.”

The buffalo given to the park by Eaton were “probably part of Alloway’s original (Manitoba) herd” (Free Press, November 2, 1963).

The buffalo Smith possessed were the descendants of the Bedson herd from Stony Mountain. Smith’s buffalo grazed on land at his vast estate in Silver Heights.

Whatever the number — seven or eight — the buffalo given to Assiniboine Park formed the nucleus of the present herd, which was augmented by later acquisitions from North American zoos.

Thirteen animals of the Smith buffalo herd were sent to Rocky Mountain Park at Banff as a tourist attraction.

The fate of the Allard and Pablo herd was put in jeopardy when the U.S. government announced it was going to open up the 1.5-million acre Flathead Indian Reservation, along the Jocko and Pend d’Oreille (Flathead) rivers in Montana where the buffalo grazed, to white settlement. Pablo first offered to sell his herd to the U.S. government, but little interest was shown. In 1906, the Canadian government proposed to buy an estimated 300 buffalo for $250 a head from Pablo and he accepted the offer. It turned out that Pablo had grossly underestimated the number of animals he had, since they were allowed to graze freely in the river valleys and no proper head count had ever been undertaken. Pablo also agreed to round-up and transport the herd by rail to Edmonton, a distance of 1,200 miles (1,920 kilometres).

Allard had passed away in 1896 and the herd of 300 buffalo was equally divided between Pablo and Allard’s heirs. Allard’s wife and four children sold off their buffalo to private buyers. It was the descendants of Pablo’s 150 buffalo that the Canadian government purchased.

At the time of the government’s purchase, Ogilvie wrote that: “Canada had one herd of plains buffalo located at Rocky Mountain Park (Banff), a few head near Winnipeg, and an obscure, apparently safely cloistered herd of wood buffalo (a separate subspecies from the plains buffalo) ranging far to the north. Apart from these few examples, Canada was bereft of what had been one of the most numerous and dominant forms of wildlife.”

The animals bought by the government were transported back to Canada. It took six years to round-up and transport the entire herd of over 700 (some sources say 709, while others claim the total was 716) Pablo buffalo to Canada (some of which would have been descended from Bedson’s original Stony Mountain herd), as with past attempts, the beasts were decidedly adverse to being corralled. “One cowboy was killed (during the round-up), ten riders suffered injuries of varying severity, a dozen horses were gored” (Free Press, November 2, 1963).

The descendents of the Allard-Pablo buffalo can now be found at Wood Buffalo National Park, a tract of land straddling the Alberta-Northwest Territories border.

Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba has a small herd of about 30 plains bison in its Lake Audy enclosure originally obtained from Wood Buffalo National Park.