by Bruce Cherney (part 2)

When Joe Daniels, who was in charge of Samuel Bedson’s buffalo herd, was bringing supplies by Red River cart to Stony Mountain Penitentiary barn yard, the high-pitched squeal of the ungreased wheels, which was typical of such conveyances, drove the prison warden’s animals into a wild frenzy, according to A.A. McDonald in his March 22, 1930, article for the Winnpeg Free Press. A mere lad of 15 years of age when the buffalo targeted Daniels, McDonald said that if the cart, ox and man had not been hurried through into the stone enclosure and the gates closed, the beasts would have made short work of all.

Manitoba’s role in preserving a remnant of the formerly vast herds of buffalo was related in a June 24, 1925, Winnipeg Tribune article quoting Charles Alloway, a Red River cart freighter and later a Winnipeg banker.

“As railways began to build across the United States, contractors hired hunters to supply buffalo meat for the workers and this was the beginning of the end for the magnificent beasts,” he said. “So that by the 1870s hunters noted that as the years rolled on, instead of finding buffalo not very far from places now known as Winnipeg, Emerson and Portage la Prairie, they had to go further west. It was back in 1873 that I conceived the idea that the day was dawning when the vast herds would be depleted. I had bought as many as 21,000 buffalo hides from a single brigade of Indian hunters, paying $3 for the average and $4 for the large ones. It didn’t take any higher mathematics to realize that this rate of killing them off couldn’t go on forever, especially as there were dozens of brigades out hunting at a time.”

Alloway and James McKay, also a Red River cart freighter, as well as a renowned prairie guide and the first speaker of the Manitoba Legislature, accompanied one brigade to Saskatchewan in 1873 with the goal of obtaining a few buffalo calves. A man was sent ahead to obtain a domestic cow to provide fresh milk for the three calves they were able to capture.

“It took all summer to get them home,” said Alloway. “... that cow got pretty tired before we were through with her.”

The calves were taken to McKay’s home at Deer Lodge in Winnipeg and placed in an enclosure. “They really did well, once they got used to our domestic cow. The cow raised the three of them.”

The two men repeated the process the next spring in 1874, obtaining “two little heifers and a husky little bull,” although the bull died en route to Deer Lodge.

“In 1877 there was a pronounced shortage of buffalo,” said Alloway, “and (in) ’79 they were practically unknown in Manitoba. By the spring of 1878 our little herd had grown from five calves to 13 animals purebred and three crossbred to domestic cattle. We realized we had something of value, although at the time we didn’t know the buffalo was practically extinct.”

A year later, McKay died and Alloway turned all his attention to the banking business with his brother, William, and decided that he could no longer manage the herd.

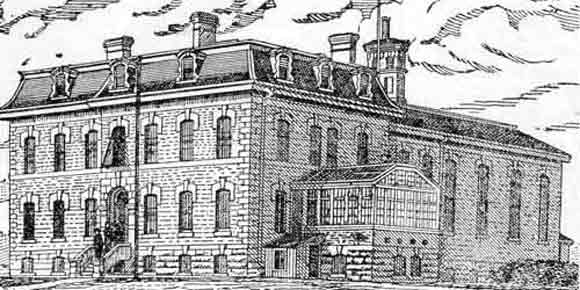

The small herd was set for auction sale on January 20, 1880. Bedson had originally believed that the buffalo were to be sold individually, but when it was announced that they were to be sold as a herd, the warden thought he was out of the running to acquire the animals, “but he had visited Sir Donald Smith and secured a loan of up to a thousand dollars (A Century of Grant MacEwan: Selected Writings, by Grant MacEwan). “When the bidding ended, probably nobody was more surprised than Bedson to find himself the owner of the last surviving herd of prairie buffalo in Canada for the unbelievable total of one thousand dollars.”

To move the herd to Stony Mountain, Bedson used two of his hired men and borrowed two riders from the McKay farm who were familiar with the Deer Lodge buffalo.

“The morning after Warden Bedson bought my 13 buffaloes,” said Alloway in 1925, “a cow dropped a calf. That same day the herds was moved 22 miles (35 kilometres) by road from Deer Lodge to Stony Mountain, round by Winnipeg. The same night they got away and came back, 18 miles in a beeline, to Deer Lodge, the one-day-old calf and its mother, trampling through the deep snow.”

(Next issue: part 3)