It’s impossible to overstate the impact the Norman Conquest had on the English language.

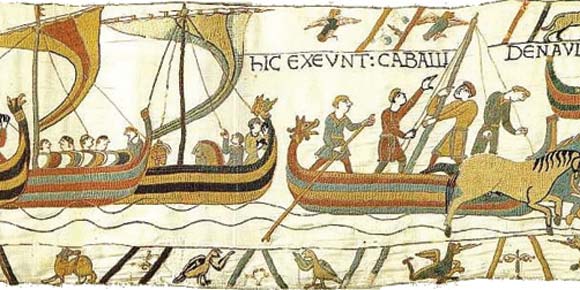

Prior to 1066, English vocabulary was almost entirely Anglo-Saxon. There was some Celtic and a little Norse but, mainly, English people spoke the German-based language of the Saxons. With the arrival of French-speaking Normans, both the country’s language and its social structure underwent immense change.

Following the conquest, Normans were installed in every important job in England. This held true both of secular and ecclesiastical positions. For almost 200 years, those who belonged to “society” spoke French not English; that is, French was the language of the court.

Naturally, even the invaders spoke some English. The Normans needed wives and they married English women. Wet nurses and other child caregivers came from the native population. Norman clerics and landowners communicated in English with their local servants and labourers. Thus, even the Normans knew some variety of “kitchen” English.

After 1204, when King John lost Normandy, English upper classes began to use more English than before. Nevertheless, that English was permeated with French words and phrases. To this day, an abundance of French is imbedded in English.

Still, scholars note fewer French words in English than one might anticipate because French truly was the vernacular of the upper classes and little of it filtered down to the lower echelons of society. Despite the barrier of class difference, it isn’t difficult to find everyday English words that arose from French.

Some are immediately recognizable as French loans. For example, picturesque, á propos (apropos), salvage, chandelier, chef, dessert and hotel.

Other vocabulary is so thoroughly incorporated into English we never question its origin. Such English is everywhere we look — in the home, in the arts, in the military, in law, even in our food.

In the home, we find chair, basin, ceiling, chimney, curtain, lamp, towel and cellar, to name but a few.

The arts overflow with French loanwords: dance, melody, music, painting, paper, poet, rhyme, sculpture, even the word art itself.

Military language bursts with French: aide de camp, ambush, combat, enemy, garrison, siege, lieutenant, sergeant and soldier. These are all words from Old French. We aren’t looking at modern loans like camouflage.

Law and order vocabulary is also filled with French derivatives: accuse, advocate, assault, crime, estate, indict, judge, jury, plaintiff, prison and verdict, for example.

French had an unusual effect on food language during its tenure in England. Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) notes this in Ivanhoe when Gurth observes that food animals are English until they die, and then they turn into Normans. He’s referring to the fact that pigs become pork (porc), cattle become beef (boeuf), calves become veal (veau), and sheep become mutton (mouton). This language shift likely arose because the French-speaking upper classes were the only ones able to afford to eat meat.

Words heard and used daily have their genesis in French. Probably no single day passes without us hearing air, city, marriage, number, nice, real, sure, remember, dinner or allow, among other everyday words of French birth.

As they say, “C’est la vie.”