by Bruce Cherney (part 3)

Despite the lack of “angels” in 1870s Winnipeg, George Ham said it was often difficult to write enough copy to fill each Manitoba Free Press four-page daily issue.

He wrote in his 1921 autobiography, Reminiscences of a Raconteur, that: “While Winnipeg in the ’70s was a sort of Happy Valley, with times fairly good and pretty nearly everybody knowing everybody else or knowing about them, the reporter’s position was not, at all times, a very pleasant one, for on wintry days, when the mercury fell to forty degrees below zero, and the telegraph wires were down, and there were no mails and nothing startling doing locally, it was difficult to fill the Free Press, then a comparatively small paper, with interesting live news.

“A half-dozen or so drunks at the police court only furnished a few lines, nobody would commit murder or suicide, or even elope to accommodate the press, and the city council only met once a week; but we contrived to issue a sheet that was not altogether uninteresting. Of course, when anything of consequence did happen, the most was made of it.”

Ham was on-hand for one of the most tumultuous periods in the young city’s history — the great speculative land boom of 1881-82. At the time, he said the city was “ablaze with the excitement of prospective riches.”

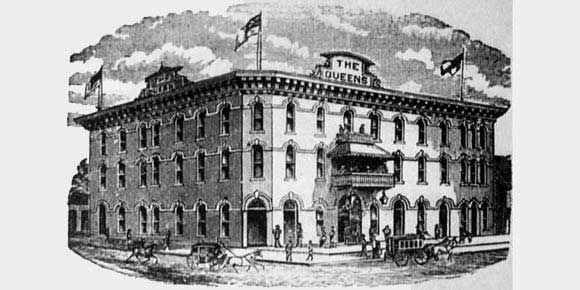

Ham boarded at the Queen’s Hotel, which was then run by Jim Ross, “at whose table a quiet coterie sat.”

Among them was La Touche Tupper, who Ham described as a good fellow, “but a little inclined to vain boasting. He was a pretty good barometer of the daily land values. Some days when he claimed to have made $10,000 or $15,000 everything was lovely. The next day, when he could only credit himself with $3,000 or $4,000 to the good, things were not as well, and when profits dropped, as some days they did, to a paltry $500 or $600, the country was going to the dogs.”

The “coterie” kept track of Tupper’s earning, which Ham claimed amounted to nearly “a million in his mind.”

But then came the bust in the speculative bubble. “And Winnipeg came down to earth again.”

The speculators were weeded out, leaving Winnipeg en masse, and investment in the city took on a more leisurely pace in the following years.

Still, Winnipeg in its early days was noted by Eastern newspapers as being one of the “wickedest places in Canada.”

Ham said there was plenty of drinking, plenty of gambling, horse racing galore, and other lively entertainment. “With dances, operas, swagger champagne suppers, and late hours, it was one continuous merry round.”

But there was also little crime. “There was scarcely even a murder or a shooting scrap and very few scandals ... and, while the bars were kept open until all hours of the night, the liquor was of a good quality, and there were few drunken people staggering on the streets than could be seen in other places which made greater pretensions of a monopoly of all the virtues ... It was simply a wide open frontier post of civilization.”

Since there was always room for opportunity in a frontier post, Ham decided to enter the ranks of the city’s entrepreneurs. Ham started his own newspaper in 1879, naming it the Tribune, the first Winnipeg newspaper bearing that name, while the second Tribune lasted from 1890 to 1980. Ham’s newspaper only had a brief history in the city, being published for just one year.

At a gathering of the Winnipeg Press Club on April 1, 1888, Ham was said to have “dropped a tear on the resting place of the Tribune, his contribution to the list of busted newspapers” (Free Press, April 2, 1888).

At the time, Winnipeg was known across North America as the “Graveyard of Daily Newspapers,” since 26 general interest daily newspapers rapidly came and just as rapidly went. One newspaper, the Manitoba Daily Herald, lasted just two weeks in 1877. Today, the sole survivor from that period — the 1870s and 1880s — is the Free Press.

In February 1880, Ham went to court to prevent Amos Rowe from naming his newspaper the Winnipeg Times, claiming he had the trademark for the name Times. Above the numerous articles about the court case, the Free Press headline was always, “The Newspaper War.”

According to court documents, Ham had purchased on January 12, 1880, for the sum of $2,000 from Edwin G. Bank & Co., “all the rights, property, interest, good will and franchises of the said firm, in the newspaper known (as) Winnipeg Daily Times.” Ham then incorporated the name Times with Tribune, the newspaper he owned.

Rowe purchased the equipment used to print the former Times on February 19, and published the Winnipeg Daily Times. Ham had earlier warned Rowe by letter against using any name incorporating the name Times, whether for a daily or weekly newspaper.

(Next week: part 4)

The judge subsequently ruled in favour of Ham.

Whatever hard feelings that may have arisen from the case quickly disappeared, as Ham became an employee of the Times owned by Rowe and other investors within a matter of days after the trial ended. The March 10, 1880, Free Press contained an announcement that the Tribune had published its last issue and its interests had been acquired by the Times.

“Two Conservative papers cannot live in Winnipeg,” according to the article. “One can, by prudent management prosper.”

Ham was noted as a Conservative Party supporter — he particularly favoured Canadian Prime Minister John A. Macdonald — but was gracious enough to also become friendly with opposition supporters. In fact, Ham became a good friend of Liberal Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier. His nickname “Genial George” was well deserved.

Ham lasted as the managing editor for the Times for two years. When he announced he was taking up the government post of land registrar for the then county of Selkirk (the county system lasted in Manitoba until 1890, when a municipal system of government was introduced), he was given a farewell banquet at Norfolk House (Hotel) on June 30, 1882. He was presented by the proprietors, editors and other staff of the newspaper with a silver set valued at $100.

“Obstinatively,” wrote John W. Dafoe, for years the city editor of the Free Press, in the Manitoba Historical Society article, Early Winnipeg Newspapers: The Last 70 Years of Journalism at Fort Garry and Winnipeg (MHS Transactions, 1946-47 season), “during the eighties, he was a registrar under the old system of Land Titles, but actually he was engaged in journalism, a good deal of the time, with a deputy in charge of his office.”

Ham lost his position as registrar when the Torrens system was introduced in Manitoba and the job required the services of a “barrister of ten years standing ... although I produced any number of witnesses that I had longer standing than that at the bar (now abolished) and so I returned to newspaper work.”

Of course, his explanation was meant to be humourous, but the reality was that he was underqualified when the Real Property Act was passed in July 1885 by the Manitoba Legislature and the Torrens system of land title transfers was introduced (The Title to Land in Manitoba, by Edwin A. Pridham, MHS Transactions, 1956-57 season).

Ham again found himself working for the Free Press. “I have Geo. Ham on temporary and am trying to fix it permanently,” wrote Dafoe in a January 1890 letter. “George is about the King-bee of Northwest newspaper men. He was city editor of the Free Press ten or 12 years ago and had quite a checkered career since then, full of ups and downs, all of which have been borne with the good nature of the genuine Bohemian.”

(Next week: part 4)