October 4 marks the anniversary of what has to be one of worst instances of extremely bad timing in Canadian history. On that day in 1957, the Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow’s first roll-out took place. The company had planned a grand ceremony with more than 13,000 guests. Unfortunately, the media and public were distracted by the launch of Sputnik on the same day.

In hindsight, it appears this was simply a harbinger of the eventual doom awaiting what was once billed as the most advanced supersonic interceptor in the world. Two years after the roll-out, on February 20, 1959, the Avro Arrow project was cancelled by Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s Conservative government, ending Canada’s then role as a global leader in aviation technology. The Diefenbaker government even used the excuse that the Arrow was made obsolete in the aftermath of Sputnik — missiles — not aircraft — would be the military weapon of the future. That turned out to be a costly mistake.

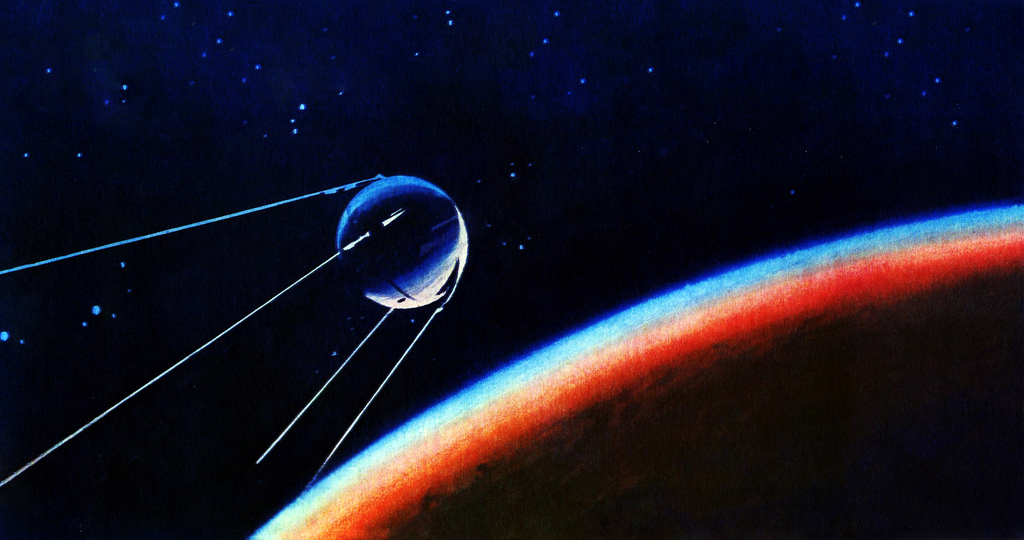

The launch of Sputnik 1 marked the beginning of the “Space Race” between the Americans and the Soviets and the commencement of the “Space Age.”

Sputnik’s simple “beep ... beep,” heard by ham radio operators around the world, created panic in the U.S. The 84-kilogram satellite, propelled into space by a R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), was seen in the U.S. as a sign that it was no longer safe behind its ocean barriers. “As Russia’s satellite circles the globe the (President Dwight) Eisenhower administration faces increasing pressure from Congress, some scientists and even from within the government itself to speed up perfection of military missiles,” announced a special report in the Winnipeg Free Press on October 7, 1957.

The Chicago Daily News declared that with the launch, “the day is not far distant when they could deliver a death-dealing warhead onto a predetermined target anywhere on the earth’s surface.” Newsweek predicted that dozens of Sputniks equipped with nuclear bombs could “spew their lethal fallout over the U.S. and Europe.” Senator (later President) Lyndon Johnson spoke of a day when the Soviets would be “dropping bombs on us from space like kids dropping rocks onto cars from freeway overpasses.”

In a typically calm and hilarious Canadian reaction, Defence Minister G.R. Peakes said he heard about Sputnik on the radio, but “could make no comment because it’s out of this world.” Future Prime Minister Lester Pearson marvelled at the scientific advancement, observing: “Somehow or other a strong dynamic impulse for national creation has been created in the Soviet Union ... As an incentive to excellence and accomplishment the outstanding scientist and engineer is put on a level of prestige ... which in our society is reserved for heroes of sport or entertainment.” Pearson said a lesson should be learned — it was a mistake to see Russians as only “moujiks and lumpish proletariats.” It was time to drop the “well-worn clichés of the superiority of ... ‘our way of life’” (i.e., a car in every garage), although there was no substitution for a society of free individuals “refusing to be pushed around ... consecrated to a worthy purpose and willing to accept the disciplines, the sacrifices and concentrated effort needed to achieve it.”

Eisenhower tried to minimize the military importance of Russia’s piercing of the space frontier, but was unsuccessful. “He misjudged the short-term public reaction to Sputnik and was unable to calm American fears,” wrote John Logsdon, director of the Space Policy Institute, Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University, in an article commemorating the 40th anniversary of Sputnik. “Also, he did not recognize many of the ways that going into space would transform life on Earth.”

With news of Sputnik orbiting the Earth every 98 minutes, millions gazed into the nighttime sky to glimpse the man-made star. “I saw the bright little ball,” wrote retired NASA engineer Homer H. Hickam in his best-selling book, Rocket Boys, “moving majestically across the narrow star field ... I stared at it with no less rapt attention than if it had been God Himself in a golden chariot riding overhead.” At the time he spotted Sputnik, Hickam was a 14-year-old lad, whose wonderment was tinged with the commonly-held American belief that their nation had let down its guard and inexplicably the Soviets had surpassed them. Until the launching of Sputnik, Americans firmly believed Soviet Russia was a technologically primitive nation. The need to confront the new reality spawned the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA).

Initially, the Soviets didn’t realize the full extent of their accomplishment. The Communist daily newspaper Pravda only printed a brief front-page article about the launch. But Western newspapers quickly grasped its significance. The New York Times said the launch was “one of the world’s greatest propaganda — as well as scientific — achievements.” Once the Soviet leadership realized Sputnik’s shock value, Pravda printed an extensive article under the banner headline, World’s First Artificial Satellite of Earth Created in Soviet Union.

The U.S. panic is puzzling, as it was widely known that as a participant in the United Nations-sponsored International Geophysical Year — a collaboration of 67 nations to explore the physical world between 1957 and 1958 — the Soviets had always intended to launch a satellite. Yet, all the information was ignored. British astronomer Sir Bernard Lovell referred to this as, “American blind disbelief in the powerful advance of Soviet science and technology.” A month later when the Soviets launched Sputnik 2, sending a space-travelling dog named Laika into orbit. The day after, the Free Press front-page headline was, Cold Sweat in Washington.

Some officials in Washington said the launch of the two satellites showed Russians had the capability “to fire a rocket to the moon, launch a space platform or station.” Of course, there were sinister implications as well — a space platform could be used for surveillance of U.S. military installations and to launch a nuclear attack. Diefenbaker gave a different spin, claiming that instead of causing alarm, the launch was another “incentive to the free world to draw on the wells of freedom and achieve in unity what we have failed to do in our weakening unity of recent years.”

Although Sputnik did intensify the Cold War, it did present an opportunity. The Americans faltered at first, but were the first to reach the moon.

The Space Age continues. On July 14, this year, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft captured images of the rugged, icy mountains and flat ice plains on Pluto. But Canada is still seeking to buy a fighter jet to replace the aging CF-18 Hornet. The dream of building a Canadian-made supersonic, all-weather interceptor effectively ended when Sputnik was launched. Ironically, 32 former Avro Arrow technicians and engineers played a significant role in the success of the American space program.