For decades, Heritage Minutes focussing on major events in Canada’s history have been airing on television. There is now a new TV entry with a similar goal to teach Canadians more about their nation’s history. The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) History Foundation has launched a new series of historical narratives that tell the story of Canada’s adventurous past.

The first spot of the Company of Adventurers series recently appeared during the Emmy Awards broadcast with Les Stroud, of Survivorman TV fame, telling the story of Arctic-explorer-extraordinaire Dr. John Rae, an 19th-century HBC employee with strong ties to Manitoba. Of course, no short segment can tell a complete story of Rae’s accomplishments, but it does introduce Canadians to a significant figure from their nation’s past.

“When I first heard about this project, I was immediately interested,” said Stroud. “I love Canadian history and these stories deserve to be told. And I was honoured to get to tell the story of John Rae, who really was one of the greatest adventurers in our country’s history.”

Stroud is a modern-day Canadian adventurer, who is placed for a week during each segment of the Survivorman series in harsh natural settings to test his skills to overcome adversity.

“We think the best people to tell Canadians about our past adventurers are modern adventurers,” said Christina Yu, the creative director of Red Urban, which partnered with the HBC History Foundation to product the series of 30-second and 60-second spots. “They help connect the past to the present in a very relevant and compelling way.”

The HBC was founded in 1670 as the “Company of Adventurers trading into Hudson Bay.” Its most important early post was Fort Prince of Wales at the mouth of the Churchill River along Hudson Bay in Manitoba. Although Lord Selkirk promoted the founding of a colony at The Forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, it was through the auspices of the HBC, which governed the Red River Settlement until Manitoba became a province in 1870.

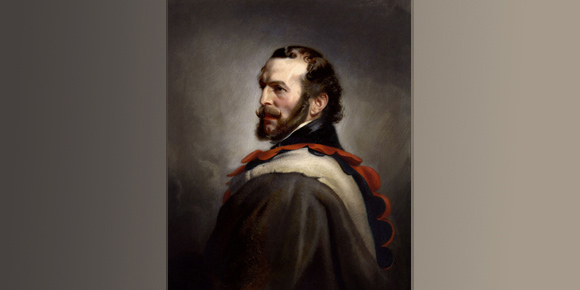

Scottish-born Dr. Rae, who worked for the HBC from 1833 to1856, is arguably the greatest Arctic explorer in Canadian history. He found the last missing link of the fabled Northwest Passage, and during his explorations worked closely with the Inuit, adopting their survival techniques in contrast to other European explorers of the era.

Most famously, he is known as the man who discovered the true fate of the doomed Franklin expedition.

Dr. Ross Mitchell wrote in Manitoba Pageant, September 1958: “Still too little known, even in Winnipeg where he had many associations, is Dr. John Rae. He explored over 1,700 miles of the Arctic coast, engaged in three searches for the Franklin Expedition and surveyed a line from Winnipeg across the Rockies to the Pacific coast for telegraph lines. His great merit as an explorer was that he knew how to live off the country. In the Arctic, he learned to use igloos and to eat food which the country provided. He was notable alike for his exploits and his character ...

“In 1846, with twelve men and two boats, Rae landed at Repulse Bay, traversed Rae Isthmus, explored a part of Melville Peninsula and wintered at Fort Hope. Part of the stone hut which he built is still standing. The stone hut was so cold that thereafter he learned to live in snow igloos. In the spring, he showed that Boothia was not an island but a peninsula. After fifteen months of exploration, he brought out all his men in good condition and heavier than when they started ... At one time in this expedition, Rae was within one hundred and fifty miles of the two ships, Erebus (this ship was found in 2014 by a Parks Canada-led expedition) and Terror, of the Franklin expedition which were beset by the ice, but he did not know of their desperate plight.”

The British Admiralty charged Franklin and his 129-man crew to travel up Lancaster Sound and then sail southwest across the uncharted central Arctic to link his earlier discoveries in the west end of the region. By following this route, it was believed Franklin would finally unravel the mystery of the Northwest Passage leading to the Orient. The expedition set out from England on May 19, 1845.

The last Europeans to contact Franklin and the crews of the two ships were whalers aboard the Enterprise and Prince of Wales in August 1845. For three years after that, not another word was heard from Franklin and it became increasingly clear that some unknown fate had claimed the captain and his men.

William Kennedy, who had retired from the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1846 and later settled in St. Andrew’s, Manitoba, was hired by Lady Franklin to lead two expeditions to find her husband, but both were unsuccessful. Arctic explorer Dr. John Rae whenever he encountered Inuit would ask if they had seen any “dead white men.” Obviously, Rae was under no illusion that anyone from the Franklin expedition had survived.

Rae compiled an account of the expedition’s fate from Inuit sources: “in the spring of four winters past ... Esquimaux ... near the shore of King William’s Land” saw “about forty white men ... travelling in company southward over the ice, dragging a boat and sledges ... by signs the Natives were led to believe that the ... ships had been crushed by the ice.” Rae’s report to the British Admiralty — confirmed by later expeditions — showed that Franklin had died in June or July 1847, and in the winter of 1847-48 no less than 24 of the men had died, nine of whom were officers. The Inuit said they found bodies in tents and under a boat used as shelter after the two ships were crushed by the ice.

From the Inuit, he purchased silver spoons and forks, an Order of Merit, and a small plate engraved “Sir John Franklin K.C.B.” He also found 35 bodies.

Dr. Rae related his Arctic explorations and the fate of the Franklin expedition to members of the Manitoba Historical Society during a presentation on October 11, 1882, in Winnipeg.

On his return to London, Dr. Rae learned that he was entitled to the award of £10,000 offered for proof of the fate of the Franklin Expedition, which he shared with his men.

But one fact he learned about the ill-fated Franklin expedition from the Inuit would dog Dr. Rae for years — the crews of the two ships had resorted to cannibalism to prolong their survival. Lady Franklin, the British Admiralty and renowned author Charles Dickens asserted that no Englishman would resort to such a barbaric practice under any circumstances. Dr. Rae’s compilation of information about cannibalism from Inuit sources were later proven to be true.

Dr. Rae died at London at age 80 and was buried in the churchyard of St. Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall, in the Orkneys.

“The Country of Adventurers captures the rich and exciting history of Canada, and hopefully encourages Canadians to learn even more about this great country,” said HBC president Liz Rodbell.

Indeed.