by Bruce Cherney (part 1)

At the Canadian Pacific Railway’s (CPR) Windsor Station in Montreal on October 2, 1927, May S. Glendennan, the president of the Canadian Women’s Press Club, unveiled a plaque with the following dedication: “To the memory of Colonel (an honourary title) George Henry Ham, official of the Canadian Pacific railway, who died in Montreal April 16, 1926. This tablet is erected by the Canadian Women’s Press club in grateful recognition of his services as their founder and friend. He was a gallant gentleman and great of heart.”

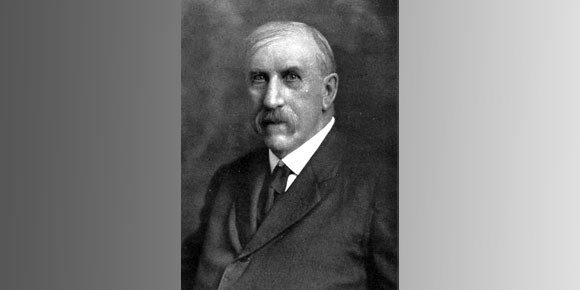

For a time, George Ham was considered among the most eminent journalists in Canada and one of the nation’s great humourists — some even referred to him as Canada’s Mark Twain, but it’s an honour that rightfully belongs to Stephen Leacock — as well as a friend to many, including royalty, prime ministers, premiers, the business elite and everyday men and women.

E. Cora Hind, the women noted for her very accurate forecasts of the annual grain production in Western Canada for the Manitoba Free Press, said Ham was, “The kindest man I ever knew.”

The August 12, 1911, Winnipeg Tribune claimed that it was doubtful “if there was a more popular citizen of Winnipeg (he lived in the city for several years) than Geo. Ham ... Born with a keen sense of humor, and with an ability to make and keep friends, it is little wonder that he holds the championship for possessing the largest aggregation of friends and acquaintances throughout the Dominion.”

Another of his nicknames was “Genial George.”

He called himself a “raconteur,” which means “a teller of anecdotes,” according to the Oxford Dictionary. His somewhat amusing autobiography written in 1921 was entitled, Reminiscences of a Raconteur.

Yet, some did call him a self-serving, self-promoter, who made outrageous assertions about his role in the history of Western Canada and the world beyond.

The Winnipeg Tribune of June 26, 1912, under the headline, Brief History of George Ham, satirically commented on a trip to Winnipeg after a long absence, saying it “is an event which cannot be lightly passed over; indeed it is an epoch in the history of this great western portion of the King’s domains ...”

It was a turn around from the praise heaped upon him in 1911, but is explained by the comment: “When George lived in Winnipeg we made him pretty nearly everything but city and provincial treasurer ..., But we made him an alderman (city councillor), a school trustee, a registrar, and editor, and Lord only knows what other honors we heaped on him.”

The newspaper claimed that, if Ham hadn’t left the city for the lure of the CPR, he would have been made mayor of Winnipeg and premier of the province.

The June 1912 article was in the spirit of good-natured fun rather than outright malice.

“It was George Ham who first inspired and organized the Riel Rebellion, and who subsequently quelled it,” according to the article.

“It was George Ham and old Tom Spence who erected that brief-lived Republic at Portage la Prairie.”

The later contribution to Manitoba history was impossible, since Ham didn’t arrive in Manitoba until 1875 and the short-lived republic was formed in 1868. But Ham did report on the 1885 Northwest Rebellion headed by Riel, although he didn’t organize it.

The newspaper ran through a series of Ham’s alleged career accomplishments, such as the creation of the Red River judicial system, the establishment of the system of land transfers in Manitoba, as well as becoming Winnipeg’s “first reporter, first mayor, first chief of police, first chief of the fire brigade, first preacher, first basemen, first pugilist and first bouncer.”

The article was accompanied by a number of cartoon drawings designed to make fun of Ham. One cartoon is of Ham holding a hankerchief to his nose with the caption, “George as chairman of Board of Health, inspecting manholes.”

In another, Ham is on his knees, “Pleading with Riel not to embark on his second rebellion.”

Ham’s brain is given prominence of place in a cartoon with the caption, “George as first chief justice.”

While his newspaper career as a writer and editor in Winnipeg brought him to national attention, it was during his time as the press agent for the CPR that he gained the gratitude of Canada’s newspaper women.

“One fine day in June, 1904,” Ham wrote in his autobiography, “a handsome and fashionably dressed lady came into my office at C.P.R. headquarters, and started cyclonically to tell me that while the C.P.R. had taken men to all the excursions to fairs and other things, women had altogether been ignobly ignored and she demonstratively demanded to know why poor downtrodden females should thus be so shabbily treated. When she had finished her harangue — I guess from lack of a further supply of breath — I politely motioned her to a seat and calmy said:

“‘Sit down, Miggsy, sit down and keep cool,’ which she did.

“She was Margaret Graham, a writer for the press, and a champion of women’s rights — which I had already sagaciously surmised.”

Ham related that Graham, who had been involved with Canadian and U.S. newspapers for 15 years, had come to his office to persuade the CPR to take a “bunch” of women on a junket to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, informally known as the St. Louis World’s Fair.

Ham said the idea appealed to him, but he told Graham the trip would only be possible if she could find 12 bona fide women journalists to participate. In the end, she found 16 women employed as journalists by Canadian newspapers — nicknamed the “Sweet Sixteen” by later writers — willing to travel to St. Louis, a journey that began on June 16.

It was during the excursion that the Canadian Women’s Press Club was formed. Among the founding members was Kate Simpson Hayes, who wrote under the pen name, Mary Markwell, and edited the Manitoba Free Press’ first women’s page in 1899. In 1904, she was acting as Ham’s secretary and living in Montreal. She contributed articles to the Free Press until 1909.

In the ensuing years, Manitoba women would play a prominent role in the press club. The first national meeting of the Canadian Women’s Press Club was held in Winnipeg in June 1906.

The Free Press reported the club’s formation on July 9, 1904, while begging its readers, “Please don’t laugh.” Although the author of the piece is not provided (bylines were uncommon during the era), it is obvious that it was written by one of the members of the new club, who had a healthy sense of humour. Perhaps, it was Ham himself, in his guise of self-promoter, but that is pure speculation. Certainly it’s in his writing style, but any of the women aboard the train were capable of writing the dispatch which was sent across Canada for publication.

George Ham was made the honorary president of the new club, while Kathleen “Kit” Blake Coleman of the Toronto Globe and Empire was elected president.

Throughout his remaining years, Ham would proudly tell the story of how he became the first and only male member of a women’s press club in the world.

When recalling the women’s press club in his autobiography, Ham wrote: “Some are born great, you know, others achieve greatness, and others still have greatness thrust upon them. You can readily see to which class I belong, can’t you?”

Under the headline, The Canadian Women’s Press Club, the Free Press reported that Ham said: “We have taken press men here, there and everywhere, and why have we not taken press women?”

A press woman within earshot of the interview in progress replied: “Because, forsooth, women are nowhere recognized. We work, we labor, we travel on railways and pay full fare. Is it our fault we are born in petticoats instead of trousers.”

The article continued by mentioning the difficulty of finding a male crew for the St. Louis bound train using comedic flair.

“The men fled at mention of a carload of ‘Angels!’ They had carried live weight hogs, western cattle, eastern beeves, baled hay, gallons of beer, firewood ... but take a carload of women across the way betwixt Montreal and St. Louis! No siree! Every man-Jack of ’em defaulted. Left without wages, good-byes, night-caps and valises; they simply couldn’t understand what was required of ’em!”

The only person to stand firm in his commitment to the cause was Ham, according to the article.

“I am bald-headed,” he said. “My will is made. I have been through wars and rumors of wars. I have lived on pemmican and served through a Fenian raid, and two rebellions, my life is of little value, let me go.”

With Ham’s resolution to proceed, the cause was taken up by other men and the train was manned. They were off to St. Louis to make history.

The women made the trip in a special pullman car and after St. Louis made stops in Chicago and Detroit, where they were enthusiastically greeted by women journalists during stopovers.

At Chicago, they were invited to the Republican convention to nominate a candidate for U.S. president. “When we entered the hall the band discovered we were Canadians, and we heard our own national anthem (then God Save the King) played ahead of Yankee Doodle ...

“When memories grow dim, and the long age looms up; when our pens, worn by reason of the years’ tracings, shall have become blunted and maybe dimly traced, one of two things will live in the minds of Canadian press women: these things are the splendid way we were met and royally entertained by our American cousins on our first trip through the domains of Uncle Sam. Another will be the thoughtful kindness of the Canadian Pacific railway, the first corporation to recognize the work of pen women.”

“The club has prospered amazingly,” wrote Ham in his autobiography, “notwithstanding my association with it, and its membership has increased from 16 to more than 360.”

(Next week: part 2)