by Bruce Cherney (part 3)

In 1912, Winnipeg was in the midst of a real estate boom, which had commenced in 1906, with much of the money invested in property coming from Great Britain.

“Real Estate is now an investment in Winnipeg and not a speculation,” claimed the financial editor of Town Topics on May 25, 1912.

L.J. Murphy, the manager of the Merchant’s Bank, 1385 Main St., predicted that in the following spring, Winnipeg “will see the greatest boom this city has ever known” (Winnipeg Tribune, June 9, 1906).

“The grain prospects for a long time was very bad, but with the advent of harvesting and the splendid samples of wheat this tendency has diminished until the citizens generally are now optimistic and have regained their confidence,” a Main Street real estate agent told a Tribune reporter (published September 14, 1907). “The real estate will begin its boom.”

But the good times were about to end.

Lot sales in Crescentwood continued at a brisk pace until coming to a virtual standstill when the 1913 recession struck (Manitoba History, Autumn 1992 — Historic Tour: Crescentwood, Winnipeg’s Best Residential District, by Rosemary Malaher).

When the recession struck in the U.S. and Canada, real income had sharply declined. In Western Canada, the “wheat boom” that began in 1896 went bust in 1913, which had a dramatic impact on Winnipeg as the city relied upon grain production to fuel its economic growth.

Droughts in the prairie wheat fields in 1913 and 1914 added to the calamity.

In anticipation of a war breaking out in Europe, foreign investment in Winnipeg and Western Canada abruptly ended. And when the First World War broke out in 1914, lenders in Britain, who were fearful of their investments, pressed mortgage lenders and implement dealers to call in prairie farmers’ loans. To collect what was owed, the farmers were threatened with foreclosure.

In Winnipeg, bankruptcies ensued in the wake of the recession.

By 1916, when wartime demand for Canadian products, including wheat, increased, the recession ended, but the economic downturn made many people cautious with their money. Was this the beginning of Winnipeggers being noted as “bargain hunters?” If so, they would certainly later achieve great bargains when buying Crescentwood land.

The September 8, 1917, Winnipeg Tribune reported that demand for residential lots, even though dramatically slowed by the recession, necessitated periodically subdividing the Crescentwood property. By that year, the 300-acre tract of land making up Crescentwood had been completely subdivided into lots.

In 1917, the streets within the subdivision were Wellington Crescent (Enderton had renamed a portion of it Crescent Road, a name that didn’t stand up to the test of time), Academy Road, Rushkin Row, Dromore Avenue, Yale Avenue, Harvard Avenue, Stafford Street, Cambridge Street, Stafford Street, Harrow Street, Wilton Street, Guelph Street, Rockwood Street, Oxford Street, Waverley Street, Amherst Street (now Avonherst Street), and Park Road (now Palk Road). Grosvenor Avenue was Crescentwood’s southern border.

That year, C.H. Enderton & Co. held 133 of the remaining lots in the subdivision that the firm couldn’t afford to keep on its books. To rid the company of the lots, Enderton came up with the well-publicized scheme of holding a public auction. He expected a rush of purchases in a single day rather than the slow pace of selling lots on an individual basis.

In a September 11, 1917, Tribune advertisement for the auction, the main selling point was that, “Every City has Its Distinctive Residential District: London has its Park Lane, New York its Fifth Avenue, Montreal its Westmount, Chicago its Lake Shore Drive, (then in bold letters) Winnipeg its Crescentwood.”

The ad promised that every lot would be sold to the highest bidder“absolutely without reserve.” Essentially, the lots were being sold for what the buyers dictated; hence, the absence of reserve bids, which was quite a gamble on the part of Enderton.

On the day of the September 15 auction, the Manitoba Free Press commented that Enderton had treated Crescentwood like a child, nurturing it from its infancy to “its high stage of perfection.

“Fifteen years ago Crescentwood was nothing more than a field of brush, but today it ranks equally with Portage avenue in its respective class, and it is probably true that just so long as Portage avenue remains the main artery of the city, so long will Crescentwood remain the choicest residential district.”

Despite praising Crescentwood as the city’s “choicest residential district,” the newspaper also predicted that the lots would likely go for a fraction of their true value, which was indeed the case.

On September 17, a Tribune subhead noted that the lots were auctioned off at prices far below their assessed value, which had been fixed by the city’s tax department.

The Free Press reported that 5,000 wouldbe lot buyers attended the auction conducted by J. Clarence Davis and Joseph P. Day, who were New York-based auctioneers. Hiring the U.S. auctioneers was another part of Enderton’s promotional plan. Also figuring in his plan was holding the auction in a big tent at the corner of Harrow Street and Wellington Crescent.

“It was undoubtedly ‘bargain day’ in real estate and many were able to secure plots of land in one of Winnipeg’s finest residential districts at prices about half their assessed value and at considerably less than half the figure at which they have been sold by the former owner.”

Prominent Winnipeggers bought some lots to build homes upon, but others were snatched up at below market prices by investors and speculators.

When the hammer dropped at midnight, 100 lots were sold. Another auction was then scheduled to sell the remaining 33 lots.

On the first day, the Winnipeg School Board bought the corner lot at Stafford Street and Kingsway Avenue for $42 per foot of frontage, which had been assessed at $90 per foot. The savings to the board was reported to be $4,656.

Manitoba Deputy-Attorney General John Allen bought Lot 43 at a price of $43 per foot of frontage. The lot had been assessed at $60 per foot.

Lot 126 was purchased by Professor W.F. Osborne at $62 a foot. “He stated later that he had been able to secure this lot as it was the one he had specifically marked out for himself.”

“P.C. McIntyre bought a lot on the Crescent at $72 per foot, which was assessed at $110, and for which before the sale the owners were asking $200 per foot.”

The Tribune related that Lot 40 was purchased by Major H.W. Wright for $33 a foot, which had been assessed by the city at $55 per foot of frontage.

When the remaining lots were sold on September 17, “there was a fairly good demand for the choice plots, especially those located on, or near to Crescent Road (Wellington Crescent).”

The newspaper reporter was told by Day and Davies that the auction did not bring the prices that were expected for a subdivision within two miles of the city centre, but those who did buy land could not fail to realize a profit when reselling, as the actual worth of the properties was well in excess of the prices paid.

“They stated further that lots in residential sections of American cities the size of Winnipeg would be worth $750 a foot, or $75,000 for 100 feet instead of $9,000.”

Day told the reporter that the sale of so many lots at low prices would lead to a home building boom in Crescentwood during the coming years.

In total, the two-day auction sale resulted in the sale of lots for approximately $500,000. The assessed value of all 133 lots placed on the auction block was estimated at $1.3 million.

The newspaper explained that the poor prices realized were the result of the real estate market peaking in 1912 and then coming to a standstill in the following years.

“C.H. Enderton and Co. are to be congratulated, first on the success of the sale, even if it did bring them a price considerably lower than what this property has been quoted in the past,” said auctioneer Day. “Secondly, for their courage in putting this property up for public bidding, in these times, and allowing the public to make their own price. It only proves what has been our experience in the past, that when you treat the public squarely they will give the proper response.”

Day said that few local citizens predicted that the sale would even bring in $500,000 due to the city’s depressed real estate market.

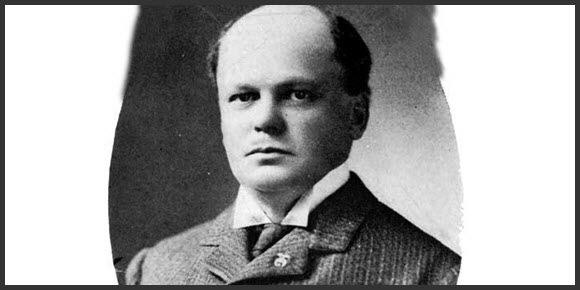

Just three years after the auction sale, on June 25, Enderton died while driving his automobile on Academy Road after taking an excursion in Assiniboine Park. He was driving a lady friend home when he collapsed. He was pronounced dead of a heart attack at the accident scene by physicians 20 minutes later. Death, according to the doctors, was instantaneous.

Enderton was born in Lafayette, Indiana, on May 4, 1861 and was orphaned by the age of three. He was educated at De Pauw University and began a law practice in St. Paul,

Minnesota, in 1884. He came to Winnipeg in 1890 and started a career in real estate. He was a co-founder of the Winnipeg Real Estate Exchange (now WinnipegREALTORS®), which was established in 1903.

(Next week: part 4)