by Bruce Cherney (part 1)

“Only four days left!” announced an Enderton Contest advertisement in the May 28, 1902, Manitoba Free Press.

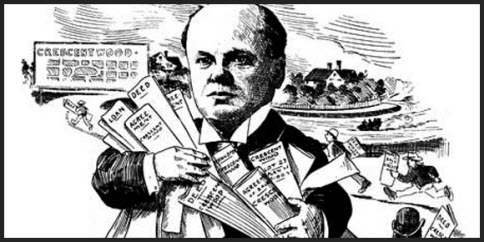

Charles Henry Enderton was offering a prize of $100 to the entrant that came up with the best name for his planned subdivision on the south side of the Assiniboine River.

Enderton called it “Winnipeg’s future best residential district.” As the ad clearly stated, the new subdivision on about 300 acres of land was “the natural situation for a neighbourhood of the highest class,” and the owners of the land believed “that the growth of the city would render necessary an entirely new district for residences of the better class.”

The Enderton ad also stated that the new subdivision would be “safeguarded by desirable building restrictions.”

In effect, Enderton and his investors in the project intended to make it an exclusive neighbourhood for Winnipeg’s elite.

The $100 prize was won by 16-year-old George Larry, who lived at 500 Gertrude St. The name he submitted to win the contest was Crescentwood. Larry said he would devote his winnings to obtain business college training.

It wasn’t exactly an original name, since lawyer John H. Munson had used the same name for the home he had built in 1888 at 475 Wellington Cres. At the time, what would become the Crescentwood subdivision was heavily wooded by elms, ash, oak and balsam trees, which resulted in Munson combining the Crescent on which he lived with wood to form the name Crescentwood.

The property that formed Crescentwood had originally been owned by Colonel James Mulligan, one of the Chelsea pensioners hired in 1848 by the Hudson’s Bay Company to keep order in the Red River Settlement. He was given a small grant of land along the south bank of the Assiniboine River. Over the course of 30 years, he acquired 360 acres that included the future Crescentwood and another 240 acres in what is now River Heights.

One of the biggest deals of the Great Land Boom of 1881-82 was Mullican’s sale of the 360 acres to Alexander Wellington “A.W.” Ross for $184,000. In the fall of 1881, Ross sold the property to J.H. Ashdown, J.W. Harris and others for $240,000, Ross re-purchased the land in early 1882 for $360,000. When the boom collapsed, it turned out to be a “paper deal” and the property reverted back to Mullican.

Disgusted — Mullican considered the land a white elephant — he sold the whole tract to T.H. Gilmour for $10,000.

Gilmour “sold the part which comprised the original Wellington Crescent (which started out as a First Nations trail along the south side of the Assiniboine) to local buyers, the late J.H.D Munson and others, who erected the first important residences on the Crescent (Free Press, February 12, 1938).

“The remainder was sold by Mr. Gilmour, about the year 1900, to Judge Cornish (no relative of Winnipeg’s first mayor, Francis Evans Cornish) and W.W. Thomas of St. Paul, who held it until 1900 ...”

In turn, the tract of land in Fort Rouge was sold to Enderton for $66,000 at a time when Winnipeg property transactions were at a snail’s pace.

A full-page advertisement in the September 11, 1902, Free Press described Enderton’s plans for Crescentwood, which later became commonly known as the “Enderton Caveat” or “Enderton Covenant.” With the widening of Wellington Crescent to 100 feet, Enderton wrote that Crescentwood’s whole distance of two miles along Wellington would be lined by river lots with a depth of 300 feet or more, “and on the other side by large lots having a depth of 200 to 300 feet or more, which will be sold only with building conditions. By terms of the deeds, the houses will have to be set well back on the lots and be limited to minium of cost.”

Houses on the lots having a depth of 300 feet had to cost over $10,000.

Enderton explained: “It is the purpose of the owners of Crescentwood reserve it only to be sold only for residences of the better class, and placed upon the market portions of it from time to time when there shall appear to be a demand for this property by people who will build homes of this class upon it.”

Other restrictions were that only a single house could be built on each lot, houses on the lots along the opposite side facing Wellington Crescent had to be located at least 100 feet from the street line and cost at least $6,000, those facing Crescentwood Park (later renamed Enderton Park) had to be at least 60 feet from the street line and cost at least $4,000, and houses on the remaining streets had to be at least 60 feet from the street line and cost at least $3,500.

The ad assured prospective lot buyers that their property in Crescentwood would be protected. “There will be no terraces, no cheap houses, no one building on the next lot in front of the line which you have chosen for your building line.”

Despite the building restrictions, the ad asserted that prices for lots were “about one-eighth the price per square foot of ordinary lots in the Hudson’s Bay Company Reserve, which was originally a 465-acre parcel of land around Upper Fort Garry, near the The Forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. The Company began selling lots in the reserve in 1877. In an attempt to make it a desirable location for the city’s elite, lots were normally 50 feet by 120 feet with a 20-foot backlane. To keep land values high, the HBC stipulated that lots couldn’t be smaller (Winnipeg: A Social History of Urban Growth, 1874-1914, by Alan F.J. Artibise).

It was claimed that the lots in the first phase of the development of the new Crescentwood subdivision were among the most affordable in Winnipeg.

Prices for lots along Wellington Crescent were listed in 1902 as being between $900 and $1,200. Those along Park Row were listed at between $450 and $700. Lots fronting Amherst Street were being sold for $550 to $600. Along Harvard Avenue, the lots were going for between $300 to $700, while lots along Yale Avenue were relatively cheaper and selling for between $300 and $400.

The terms for the purchase of a lot were one-fourth in cash, with the balance payable in one, two and three years at an interest rate of six per cent per annum.

The lots were being offered for sale at the office of C.H. Enderton, 393 Main St., beginning at 10 a.m. on September 18.

After the sale ended on September 24, a next day ad in the Free Press claimed that over 30 lots of 100 lots available had been sold, with 16 sold to Winnipeg businessmen and professionals. But it was evident that lot sales were slower than expected, the result of the site having yet to be fully serviced.

“Just as soon as the sewers can be built and the streets paved (and this work will be pushed as rapidly as possible) there is no question that this district will be quickly built up,” according to the ad.

Clarence D. Shepard, who came to Winnipeg in 1904, who collaborated with Enderton in developing Crescentwood and bought a lot at 10 Amhurst Street in the subdivision in 1905, explained in a January 7, 1948, Free Press article that the area was remote when he arrived. “We had no buses, and had to walk across an old wooden bridge at Academy road to catch the street car.”

A Winnipeg Tribune reporter visited the office of Enderton and filed an article on July 29, 1904. According to the reporter, Enderton’s office was filled with charts and maps of Crescentwood, and on a table there were the future plans for developing the subdivision.

“This new residential section is in Fort Rouge immediately opposite Armstrong’s Point,” Enderton explained to the reporter.

“The most important point in connection with this part of the city just now, and indeed with the whole of Fort Rouge, is the plan to change Wellington Crescent. This new street will be placed parallel with the (Assiniboine) river and will make a magnificent drive leading out to the new suburban park (Assiniboine Park).”

Enderton said Wellington would not have a streetcar service, “and a building limit as high as ten thousand dollars in some localities will keep the character of the street the very best.

“Crescentwood is not being pushed just now. It is rather being prepared for pushing on the market, Three and a half miles of sewers have been put in, sidewalks are applied for for (sic) the whole district, and in fact, Crescentwood is about ready to make a brilliant debut among the residential sections of Winnipeg.”

(Next week: part 2)