by Bruce Cherney (part 4)

“It was wonderful how excited newcomers became within a week after their arrival (in Winnipeg),” wrote Charles Napier Bell (published in the April 23, 1887, Winnipeg Daily Sun). “The first day was spent by a speculator in walking about the streets and gazing in astonishment on the hurly burly of the real estate auction rooms, and he came to the conclusion that the people were completely insane.”

The next day, according to Bell, the speculator observed men reselling lots during the great land boom of 1881-82 that had been purchased the day before at an advance of 10 per cent.

“On the third day, with considerable trepidation, he invested perhaps in one small low-cost lot, situated in a town out west, which, according to the advertised plan, was expected to be a second Chicago within three years.

“On the fourth day he invested a larger sum, and was thunderstruck when he found he could sell his first purchase immediately at an advance.”

By the fifth day, Bell wrote, the man had visions of becoming a millionaire and engaged in larger purchases, all the while lamenting having passed up on other deals.

“As soon as he regretted the neglecting of past opportunities it was all up with him, for within twenty-four hours he might be rushing about, his pockets overflowing with plans of town sites and sub-divisions of river lots, while his bank account rose and fell with alarming regularity and, in fact, he had caught the contagion, and was one of the worst cases of insanity the city could produce.”

Shed Lambert told a reporter for the Bismarck Tribune (published on March 10, 1882) about the “regular old fashioned real estate craze” in Winnipeg upon his return to the U.S. community.

Lambert said he had never experienced anything similar. Train loads of speculators arrived daily, “investing their ready cash with childlike simplicity.”

A reporter for the London (Ontario) Advertiser, (article reprinted in the Winnipeg Daily Sun on August 20, 1881), wrote in amazement about the boom and the amount of business being done in the city.

“The real estate offices proper are crowded daily, and transfers are of an hourly occurrence.”

According to Scott, business was brisk in September 1881 and real estate agents were becoming numerous, “and property for sale by auction got so plentiful that it had to be refused by the principal auctioneers.”

In an article published in the Winnipeg Tribune of March 20, 1937, entitled My Discovery of the West, renowned Canadian humourist Stephen Leacock wrote of his father coming to Winnipeg during the boom and opening a real estate office, “with a sign in blue and gold thirty feet long.” His partner was an Englishman and the two “lasted nearly a year before they blew up.” Meanwhile, his uncle thrived as a land speculator.

It was reported that there were some 300 real estate signs hung up in the city at the height of the boom.

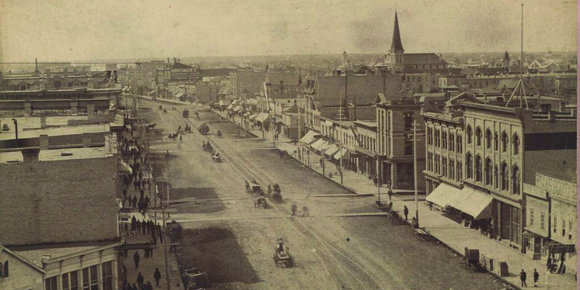

Another phenomena was the “mammoth canvas covered real estate advertising wagons” that plied Main Street daily, according to March 16, 1882, Free Press, which proposed that the wagons be converted into mobile real estate offices.

“In size they are very little inferior to the average board offices, while in appearance they are superior. The sides could be covered with suitable maps to be studied while the car was in motion, and bargains could be completed in travelling to and fro.”

The expense of renting an office for $100 a month could be saved by employing the wagons for the same purpose.

Bell recalled that in February and March 1882 there was a steady sale of real estate in the city. Twenty lots in Fort Rouge, opposite Armstrong’s Point, sold for $1,000 each.

In one week, four chains of Lot 9 in St. Boniface changed hands three times and the seller in each case realized a profit of $6,000.

“A lot on the north side of the CP track, which in the early part of the boom had been purchased for $500, was now sold for $13,000 and afterwards mortgaged to the city sinking fund for $11,000. It was estimated that at one time the deposits in the city banks reached to an enormous sum of $6,000,000.”

Bell further told the tale of a young man from Toronto who was given $400 by his father to make his fortune in Winnipeg. Upon arrival, he had $300 left in his pocket and went out on the town. While at a real estate office, he purchased a lot, making a deposit of $200 — something he forget while in his cups. When he sobered up the next day, he found that he only had a $10 bill left.

He went to the hotel front desk to settle his account and was delighted to hear he had paid it the day before, and had even purchased advance accommodations for another week.

He went to the telegraph office to wire home for more money to travel back to Toronto, but there were so many people in the line that it proved to be a long wait.

“A wild-eyed, haggard-looking individual” entered the office and shouted out, “You own lot so-and-so!”

Finally recalling his trip to the real estate office, the young man fished out from his pocket a piece of paper “covered with a few hieroglyphics, amongst which lot __ were discernable.”

He showed the paper to the “wild-eyed” man, who asked how much he would take for the lot.

The young man countered by asking what he would pay and to his astonishment was told $10,000.

“Hastily abandoning the idea of telegraphing his father he dickered with several men and finally secured $26,000 for the privilege of withdrawing his original deposit of $200 and surrender of the deposit receipt.”

Bell wrote that the young man was wise enough to depart for Toronto with a bank certificate in his pocket. When he arrived home with his new-found wealth, he was enthusiastically greeted by his delighted parents.

But it wasn’t just men who were benefiting from the boom. An Easterner wrote home that women, “who a few years ago were cooking and washing in a dirty little back kitchen, now ride about in carriages and pairs, with elegant looking individuals for coachmen sitting in the back seat driving, the mistress looking as if the world were barely extensive enough for her to spread herself in.”

“Speculators were heroes, profiteers were the new nobility,” wrote Pierre Berton in his book, The Impossible

Railway.

“Everyone in Winnipeg, it seemed, was affluent — or believed himself to be.”

Speculators who made money boasted about their good fortune to newspaper reporters, who gleefully wrote articles quoting the successful entrepreneurs. Reporters were also often rewarded for using exaggerated prose to describe the depth of the boom and the resulting accumulation of wealth. In one instance, Wolf presented a gold watch to a reporter, who then unashamedly boasted of his good fortune in print.

Of course, the newspapers were flourishing due to the many advertisements placed by auctioneers and real estate companies promoting properties for sale. These weren’t inconspicuous promotions, as a single ad might fill an entire column length or two, or even a full page.

Scott wrote that the rule for private sales was: “Settle for tomorrow what you brought today.” In many instances, a property was sold two or three times before tomorrow came, and the last purchaser got the deed, while the previous owners stood around till the deal was closed and they got their profits.”

A report in the December 30, 1882, Free Press indicated that “property sold nearly half a dozen times before there was conveyance, curbstone brokers trading entirely on receipts having little or no capital to conduct operations .... there are instances where the same lots have changed hands and have been registered as often as twenty times during the year.”

The newspaper stated that during the first three months of the boom in 1882, the City Registry Office was crowded from the hour it opened until it closed for the day. The registry employed as many as 20 clerks to record the transactions flooding into the office.

“During this period ...,” wrote Scott, “many profitable purchases were made, Conklin & Fortune bought the Donaldson potato patch ... for $15,000, and were considered insane for so doing, but the next day they were offered an advance of $5,000, which was increased to $10,000, and three months after an easterner wished to take a half interest at a valuation of $90,000. They subsequently sold it for $110,000.”

The City Registry Office reported that transactions ranged between $25,000 and $125,000 each during the boom in 1882, with two of the properties selling for $100,000 each, in the heart of

the city.

According to the registry report in December of that year, a corner of Portage and Main property was bought five years earlier for $10,000, three years later it changed hands for $15,000 and on the eve of the boom in 1881 sold for $40,000. The next fugure quoted was for $50,000, and a short time later it sold for $90,000.

(Next week: part 5)