It should come as no surprise that it was an Inuit who recently led the Arctic Research Foundation’s (ARF) Martin Bergmann research vessel to the location of the HMS Terror, one of two vessels used in the ill-fated John Franklin expedition. The HMS Erebus was discovered in 2014 by a group led by Parks Canada. When the two British Navy vessels went missing in 1845, the Inuit also provided valuable information that was used to determine the eventual fate of Franklin and his doomed expedition members.

Sammy Kogvik, an Inuit from Gjoa Haven in Nunavut, told MacLean’s magazine, he was riding his snowmobile across the ice in Terror Bay, off the south coast of King William Island in Canada’s High Arctic. He stopped to make sure his hunting and fishing companion, James Klungnatuk, was still following his tracks. When he dismounted, he noticed something unusual off to his left: a heavy wooden pole sticking out of the ice to the height of a man.

Kogvik felt it was probably the mast of one of two ships — Terror and Erebus — that “they’ve been looking for so many years.” While Kogvik hugged the mast, Klungnatuk snapped a photo. But Kogvik later lost his camera and decided not to tell anyone about his find. Klungnatuk died in an ATV accident a year later, so only Kogvik remained to tell the tale.

Yet in early September, Kogvik told Adrian Schimnowski, who is a Winnipeg artist and runs former BlackBerry billionaire Jim Balsillie’s ARF’s ship, Martin Bergmann, and the eight crew members from the Royal Canadian Navy about his discovery seven years earlier. On September 3, Kogvik led the crew, of which he was a member, to the discovery of the Terror, which was found virtually intact in 24 metres of water.

For years, Inuit had told other researchers about the presence of a ship in Terror Bay, but they were ignored. On the other hand, Schimnowski listened and was rewarded. When asked why he told his story to Schimnowski so many years later, Kogvik replied that he trusted him and didn’t trust Parks Canada or its other federal government partners, “because they like to keep everything secret.”

There had been grumblings in 2014 in Gjoa Haven when Parks Canada announced the discovery of the Erebus at a tightly-controlled news conference in Ottawa that featured then Prime Minister Stephen Harper. Parks Canada had also ignored locals who suggested Terror was at the bottom of the Arctic bay named after the ship.

“I don’t think they really took it seriously,” Franklin historian and Gjoa Haven resident Louie Kamookak told the Nanatsiaq News. “There’s a lot of modern information of a ship being seen there, under the water, from hunters and also from airplanes.”

Parks Canada archeologists later arrived on the scene and confirmed the discovery of the Franklin ship.

According to the MacLean’s article by Chris Sorenson, it was no surprise that Schimnowski earned Kogvik’s confidence. Balsillie hand-picked the Winnipeg resident to run his Arctic charitable expedition, because the soft-spoken man had a knack for working with locals and functioned like a “northern Swiss Army Knife.” He also oversaw the setup of art workshops and science labs in the North that are ingeniously housed in solar-powered shipping containers, wrote Sorenson.

Schminowski’s not ignoring the Inuit is reminiscent of an earlier explorer, who also listened to the Inuit and learned the fate the 128 men in the doomed Franklin expedition.

Scottish-born Dr. John Rae, who worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company from 1833 to1856, is arguably the greatest Arctic explorer in Canadian history. He found the last missing link of the fabled Northwest Passage, and during his explorations worked closely with the Inuit, adopting their survival techniques in contrast to other European explorers of the era.

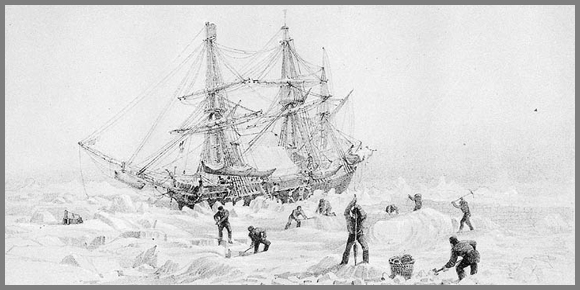

The British Admiralty charged Franklin to travel up Lancaster Sound in the two vessels — specifically outfitted for Arctic waters with reinforced iron-plated hulls and steam engines — and then sail southwest across the uncharted central Arctic to link his earlier discoveries in the west end of the region. By following this route, it was believed Franklin would finally unravel the mystery of the Northwest Passage leading to the Orient. The expedition set out from England on May 19, 1845.

The last Europeans to contact Franklin and the crews of the two ships were whalers aboard the Enterprise and Prince of Wales in August 1845. For three years after that, not another word was heard from Franklin and it became increasingly clear that some unknown fate had claimed the captain and his men.

Whenever Dr. Rae encountered Inuit, he would ask them if they had seen any “dead white men.” Obviously, Rae was under no illusion that anyone from the Franklin expedition had survived.

Rae compiled an account of the expedition’s fate from Inuit sources: “in the spring of four winters past ... Esquimaux ... near the shore of King William’s Land” saw “about forty white men ... travelling in company southward over the ice, dragging a boat and sledges ... by signs the Natives were led to believe that the ... ships had been crushed by the ice.” Rae’s report to the British Admiralty — confirmed by later expeditions — showed that Franklin had died in June or July 1847, and in the winter of 1847-48 no less than 24 of the men had died, nine of whom were officers. The Inuit said they found bodies in tents and under a boat used as shelter after the two ships were crushed by the ice. From the Inuit, he purchased silver spoons and forks, an Order of Merit, and a small plate engraved “Sir John Franklin K.C.B.” He also found 35 bodies.

Dr. Rae related his Arctic explorations and the fate of the Franklin expedition to members of the Manitoba Historical Society during a presentation on October 11, 1882, in Winnipeg. On his return to London, Dr. Rae learned that he was entitled to the award of £10,000 offered for proof of the fate of the Franklin expedition, which he shared with his men.

But one fact he learned about the ill-fated Franklin expedition from the Inuit would dog Dr. Rae for years — the crews of the two ships had resorted to cannibalism to prolong their survival. Lady Franklin, the British Admiralty and renowned author Charles Dickens asserted that no Englishman would resort to such a barbaric practice under any circumstances. Dr. Rae’s compilation of information about cannibalism from Inuit sources was later proven to be true.

“I guess you can call it Karma,” Schimnowski said in the MacLean’s article about how events unfolded and led to the discovery of the Terror. “Good things happen when you put people first.”

Indeed. It does pay to listen to locals who have an intricate knowledge of their environment. It’s a lesson that needs to be used by others following in the footsteps of Dr. Rae and Schimnowski.