Millennia before Christopher Columbus “sailed the ocean blue” in 1492 and landed in the Bahamas to be claimed as the “discoverer of America,” and the Norse landed in Newfoundland and created a brief settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows around AD 1000, a group of explorers had already set foot in North America. They were aboriginal people of Asian descent, but when and how they made their entry into the interior of the continent is still a matter of speculation.

For 60 years, the theory had been that the first inhabitants of North America — termed the Clovis culture — came across Beringia, the land bridge between Alaska and Siberia, about 13,000 years ago, and entered the interior through the ice-free corridor emerging east of the Rocky Mountains. They are considered the ancestors of today’s First Nations peoples. But, in recent years, intriguing new archaeological finds have started the process of rethinking who actually were the first inhabitants of North America.

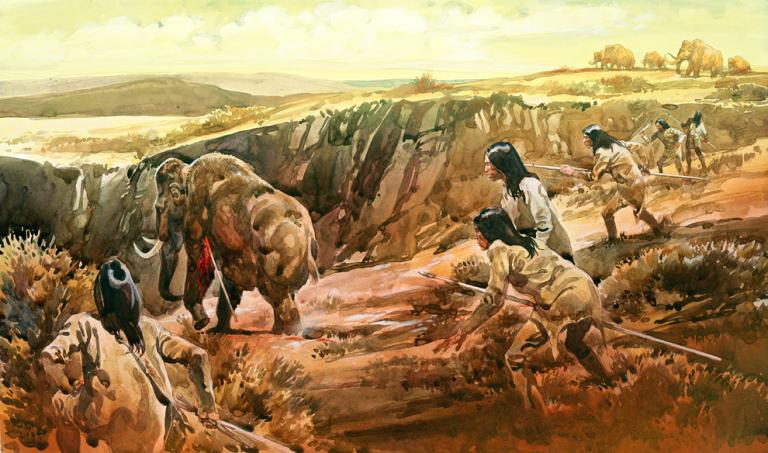

The so-called first aboriginal inhabitants from northern Asia are named from the Clovis site discovered in New Mexico in the 1930s. Excavations across North America, including Manitoba, show evidence of the Clovis people. Clovis hunters used finely crafted, fluted (groove at base) projectile points. The finding of such points embedded in mammoth remains show the hunting prowess of these early North Americans.

Clovis points have been found along the high ground of the Manitoba Escarpment, which is the remains of a beach that had existed along the shore of glacial Lake Agassiz. In all, 55 beaches associated with Lake Agassiz have been found in Manitoba. This escarpment became the natural highway into southwest Manitoba for Clovis hunters. At the time, most of Manitoba was either under water (Lake Agassiz) or covered by a massive glacier that had begun to retreat.

Clovis sites in North America contain implements such as bone tools, stone scrapers, hammers and unfluted and fluted projectile points.

But there’s growing evidence from sites in North and South America that pre-Clovis people may have set foot on the two continents, such as at Monte Verde in Chile and the Friedkin site in Texas.

During this last Ice Age, just south of the ice sheet were grasslands stretching from what is now the Central Great Plains and the Midwest to the eastern seaboard and southern Mexico. Large herbivores, such as mammoths, camels, horses and giant ground sloths and bison, thrived on the grasses, and were preyed upon by short-faced bears, dire wolves, lions, cheetahs and saber-toothed cats, all of which became extinct about 10,000 years ago.

That aboriginal people entered the interior of North America through an ice-free corridor that opened up east of the Rocky Mountains in Canada, as the two great ice sheets retreated, was challenged by a new study published in the journal Nature. An international team of Danish, Canadian and American researchers concluded that it was impossible for the Clovis people to have entered the corridor as it was then a barren wasteland unable to support humans.

“The bottom line is that even though the physical corridor was open by 13,000 years ago, it was several hundred years before it was possible to use it,” said Professor Eske Willerslev, and evolutionary genetist from the University of Copenhagen, who led the research team.

The team collected evidence that included radiocarbon dates, pollen, macrofossils and DNA taken from lake sediment core at a “bottleneck,” one of the last parts of the corridor to become open now partly covered by Charlie Lake in B.C. and Spring Lake in Alberta (University of Copenhagen article, August 10).

The data collected by the research team clearly showed that “before about 12,600 years ago, there were no plants, nor animals in the corridor, meaning that humans passing through it (it was 1,500 kilometres long) would not have had resources vital to survive.”

The fact that Clovis people were already south of the corridor more than 12,600 years ago, means they could not have reached the interior of the continent via the corridor. Instead, it is believed they — and possibly earlier groups — reached the interior not covered by glaciers by travelling along the Pacific coast either by foot or in boats.

The route along the coast was first proposed in the 1970s by Knut Fladmark, a professor at Simon Fraser University. But, this proposal was ignored for years until Alexandra Dukrodin and her colleagues at the Geological Survey of Canada also concluded that the ice-free corridor between the two ice sheets in Canada was impassable until about 12,000 years ago. Their published papers showed, by mapping river routes and land formations, that the glaciers had met, barring the interior of the continent for both humans and animals.

Even when the corridor first opened as the Ice Age ended, it would have been a swampy wasteland. Icy, Arctic winds would have blasted through the tunnel between the glaciers, making it devoid of vegetation and thus the animal prey needed to feed early human migrants.

But it took the most recent research to provide the proof necessary to uphold Fladmark’s and earlier researchers’ theories about the corridor being devoid of life.

Fladmark wrote that it would have been relatively easy for people using boats to reach Chile over 13,000 years ago, stopping to eat seals, fish and other marine animals. Indeed, boat travel is significantly faster than walking.

“Movement along the entire coast could have occurred within 200 years if people were driven,” he added.

The evidence for ancient mariners is compelling. Aborigines reached Australia about 55,000 years ago using water craft — the only way they could have covered the 100 kilometres of open water separating the island continent from nearby land.

Around 12,600 years ago, steppe vegetation started to appear in the ice-free corridor, followed by animals, such as bison, wooly mammoths, jackrabbits and voles. Then 11,500 years ago, the international team of researchers identified a transition to a parkland ecosystem, full of trees, as well as moose and bald-eagles. A boreal forest — spruce and pine trees — emerged 10,000 years ago.

“There is compelling evidence that Clovis was preceded by an earlier and possibly separate population, but either way, the first people to reach the Americas in Ice Age times would have found the corridor itself impassable,” said David Meltzer, an archaeologist at Southern Methodist University and co-author of the August Nature study. “Most likely, you would say that the evidence points to their having travelled down the Pacific Coast.”

What can now be said about the new discoveries is that they are intriguing and add more information to be considered when discussing the origins of the first people who came to the New World. And, it wasn’t Columbus or the Norse by any stretch of the imagination.