by Bruce Cherney (part 1)

The Canadian Aircraft Company Ltd., with a downtown office in the Aikins Building and a hangar at the St. Charles Aerodrome, billed itself in 1920 as the “Pioneer Winnipeg Company.” It was an appropriate claim, as the company was a pioneer in the field of local aviation.

The company was established a year earlier by Capt. G.A. Thompson and Capt. A.L. Cuffe, “after some difficulty in interesting several businessmen and bought two Curtiss planes and ground for an airdrome and hangar at St. Charles,” according to the May 7, 1920, Manitoba Free Press.

Their initial success in taking paying customers for “joy rides,” attracted more investors and under the management of F.E. Cole became a financially viable enterprise. In fact, the growing bottom line allowed the company to purchase five Avro 504 aircraft from England, which brought it to the next stage of reselling the aircraft to Western Canadian companies. Two of the five airplanes were sold to the Edmonton Aircraft Company.

In a February 18, 1920, Winnipeg Tribune advertisement, the company offered to Avros with 110 hp Le Rhone rotary engines, FOB at Winnipeg, for $4,000 apiece.

The aircraft arrived in Winnipeg in pieces and were reassembled by skilled mechanics.

“This season in addition to the two Curtiss planes operated last year,” reported the Free Press article on its first year of operation, “there will be five Avros, the first of which made its trial yesterday with Capt. F.J. Stevenson. Capt. Stevenson was taken on by the firm at the beginning of the season, when he returned to Winnipeg from Russia (to fly with the Royal Flying Corps against the Lenin-led Communists), where he was sent after the ( November 11, 1918) armistice (ending the First World War).”

Stevenson was among the hundreds of Canadian aviators who had flown with the Royal Flying Corps (later Royal Air Force) during the war, such as the famous aces Ontario’s Billy Bishop and Manitoba’s Billy Barker. After the war, they formed the nucleus of the fledgling aircraft industry in Canada, taking to the skies as bush pilots and barnstormers. The latter was an occupation that kept such companies as the Canadian Aircraft Company financially afloat until a market for other commercial opportunities arose.

As barnstormers, the CAC pilots flew to nearby town fairs and exhibitions and summer resorts to demonstrate their skill with an airplane and take people up into the air for joy rides. At the time, airplanes were still a novelty, even though the first recorded flight in Winnipeg occurred when American Eugene Ely took to the air in a four-cylinder Curtiss aircraft in 1910 during the annual Winnipeg Industrial Exhibition.

Thompson and Cuffe were said to have taken hundreds of Winnipeggers on joy rides in 1919, including Mayor Charles Gray, “who is so fond of going up in the air that he flies at the slightest excuse.”

The mayor was a passenger on a flight made by Thompson from St. Charles Aerodrome, along Portage Avenue, near Headingley, on July 22, 1920. A front page photo in the Tribune shows the mayor clad in flight gear, including a heavily-lined leather coat and goggles, with pilot Thompson, standing beside a three-seater Avro 504 airplane.

In the spirit of the novelty of flying at the time, the newspaper enthusiasm reported the two made the 140 mile flight in 90 minutes, “a rate of more than a mile and a half a minute.”

In the third seat was mechanic E. Staples. Mechanics were essential passengers, since the flimsy biplanes of the era were prone to repeated breakdowns, although the Brandon flight was without incident.

While in Brandon, Thompson took up a number of joy-riders.

Another aspect of barnstorming was wing-walking. The CAC put on a demonstration of the daring act in May 1920 at the St. Charles airfield.

“We are opposed to ‘stunt’ flying, because we believe it retards the development of aviation,” pronounced an unnamed director of the company in a May 14 Tribune article. “But wing-walking is not a ‘stunt.’ It is to be demonstrated to instill confidence in the public in aviation.”

While wing-walking may not have been a stunt as seen by the company director, it was in the repertoire of many barnstormers as a decidedly risky undertaking to marvel the public viewing from the firm ground below.

Apparently, the aviation company did discover new money-making schemes, since the Tribune reported on June 9, 1920 that P.P. Wardlaw of Amarillo, Texas, had closed a deal with Horace C. Webb, president of the American Land and loan Company, to buy a farm that he had viewed across the wings of an Avro aircraft at Dufrost, Manitoba, which is 74 kilometres directly south of Winnipeg.

“It was the quickest deal I ever made,” said Webb. “We will take this means of showing land regularly in the future.”

It was claimed by Webb that it was the first time in North America “that a real estate company has given a purchaser a real ‘bird’s eye’ view of his property.”

The Texas buyer enthused as being “delighted with such modern methods.”

While at Dufrost, Webb “gave several women trips in the plane” piloted by Stevenson.

Another pioneering aviation enterprise was Free Press reporter Cecil Lamont being flown to Winkler to cover a $19,000 bank robbery on October 13, 1920 (a story for a later Heritage Highlight column).

But the most treacherous flight for the CAC came later in the same month.

Fur trader Frank J. Stanley walked into the CAC office in the Aikins Building on McDermot Avenue and asked to be flown to The Pas, some 800 kilometres north of Winnipeg. It was a trip no one had ever made over unknown terrain and in a flimsy aircraft with a limited range.

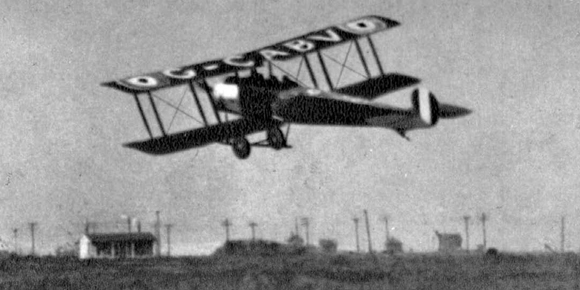

The Avro 504 biplane was first flown in 1913 and saw service in the First World War. By the end of 1914, it was obsolete as a front line reconnoissance/bomber, so the aircraft was turned into a trainer and became the most mass-produced aircraft of the war.

Following the war, a civilian version labelled the Avro 504K came into production. The British Avro Company, as well as the companies it licenced to build it, such as CAC, didn’t end its production until 1932, attesting to the biplane’s popularity as a military trainer and a civilian commercial aircraft. The CAC purchased the civilian version with an enlarged cockpit to seat two passengers in the front, with the pilot flying from the rear cockpit.

The aircraft’s all-wooden and fabric construction included a square sectioned fuselage and a single skid between the front wheels, a feature that made the biplane easily identifiable.

Pilot Hector Dougall and mechanic Frank Ellis were undaunted by the task of being the first to fly beyond the 53rd Parallel. They studied maps — not always accurate during that era — and came up with a plan to follow the route of the Hudson Bay Railway (HBR) line to The Pas, located at the confluence of the Pasquia River and the Saskatchewan River, on the northward leg of the trip.

(Next week: part 2)