by Bruce Cherney (part 1)

The early quests for the fabled Northwest Passage were driven by the European obsession for the legendary riches of the Orient, denied to them by the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453. It was long believed that there was a short sea route, linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, that could be used to replace the lost Mediterannean Sea and overland route (Silk Road) to the Far East.

The obsession spawned a series of expeditions in search of the passage that were marred by frustration, futility and frequent tragedy.

The quest for a sea route westward to the Orient was what motivated the voyages of Christopher Columbus, but barring the way for the explorers who followed was the large landmass of the Americas.

The barrier led King Henry VII of England to commission John Cabot to try to find a successful route further to the north. On March 5, 1496, Henry VII gave Cabot and his three sons letters patent with the following charge for exploration: “...free authority, faculty and power to sail to all parts, regions and coasts of the eastern, western and northern sea, under our banners, flags and ensigns, with five ships or vessels of whatsoever burden and quality they may be, and with so many and with such mariners and men as they may wish to take with them in the said ships, at their own proper costs and charges, to find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.”

Over the course of his two voyages, Cabot landed in Newfoundland in 1597 and a year later on the North American mainland, but failed to find the fabled passage to the Orient.

His failure prompted the British to seek a passage still farther to the north, through the treacherous, ice-choked waters of Canada’s Arctic Archipelago. It was a labyrinth of islands that presented challenges of a magnitude that the early British explorers were unprepared to overcome.

John Davis in 1585 entered Cumberland Sound, Baffin Island, but a route to the west eluded him when his ships were blocked by the Arctic ice. Davis Strait is named after the explorer.

Martin Frobisher attempted three times to find the passage in 1576, 1577 and 1578. Next came Henry Hudson, whose disastrous voyage ended in mutiny and those loyal to him, including his teenage son, being cast adrift in a small boat in the massive bay named for him. The mutineers returned to England, but Hudson and his castaways were never heard from again.

Sir Thomas Button was sent to find and rescue Hudson and explore for the Northwest Passage in 1612-13, but he found neither. Instead, he made landfall along the Nelson River, which was named by Button after his ship master Robert Nelson, who had died at modern-day Port Nelson, where Button erected a cross dedicating the land to James I of England and named the region New Wales. Button and his crew are noted as the first European explorers to set foot in what later became known as Manitoba.

But Britain was not the only nation seeking the Northwest in Canada’s Far North. Under the auspices of King Christian IV of Denmark, Captain Jens Munk (sometimes spelled Munck) set out with 64 men and two ships to discover the Northwest Passage to the Indies and China. It was a voyage of discovery marked by tragedy on a grand scale, the first of its kind in the annals of European Arctic exploration, although far from the last, as well as the first such tragedy to befall Europeans while in Manitoba. Among Arctic explorers of his era, Munk is arguably the least remembered today, which is unfortunate given his Manitoba connection.

The Danish claim to Greenland (today, it remains an autonomous country in the Danish realm) was made during voyages to the ice-capped island in 1605-07 under the flag of Christian IV. The voyages were undertaken to find out what had happened to the first Norse settlements on Greenland and also to discover the illusive passage to the Far East. although Munk’s specific sailing instructions have not been preserved.

From 986, Greenland’s west coast was settled by Icelanders and Norwegians, starting with a contingent of 14 boats led by Erik the Red. These settlers formed three settlements — known as the Eastern Settlement, the Western Settlement and the Middle Settlement — on fjords near the southwestern-most tip of the island, although these settlements had vanished by the early 15th century. The cause of their demise was unknown at the time when Munk set out to discover their fate for the Danish king.

In 1609, Munk was sent out to find a navigable Northeast Passage, north of Siberia, but a solid icefield on the Barents Sea forced his return to Denmark.

Until 1619, no other European explorer after Button had penetrated as far west as Hudson Bay, although the Hudson Strait leading to the bay had been surveyed by such explorers as Robert Bylot and Baffin. Yet, Baffin returned to England in 1615 and confidently announced that the Northwest Passage could not be achieved through Hudson Strait.

“A statement like that, if Munk knew about it, would probably not have discouraged him at all,” wrote Jon Carlsen in Jen Munk’s Search for the North West Passage in 1619-20 and His Wintering at Nova Dania, Churchill, Manitoba. “It was not until 150 years after Munk’s expedition to Hudson Bay in 1619-20 that the world was convinced that there was no passage from there to the Pacific.”

Munk, an experienced sailor, who was born in Norway in June or July 3, 1579, but came to Denmark at age eight with his mother, had sailed as far afield as Brazil, before returning to Copenhagen in 1599.

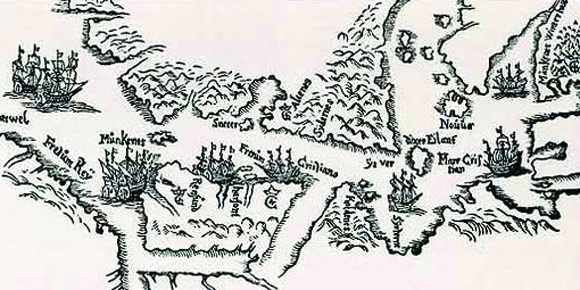

One advantage Muck had was the knowledge of the Arctic waters acquired from the voyages and charts — although often sketchy and frequently somewhat unreliable — of those who had preceded him.

In 1624, Munk published his diary, Navigatio Septentrionalis, in Danish, which provides an account of his Arctic voyage. It is only in recent years that the bad translations of the past have been rectified and accurate English versions of his diary have been published.

Munk and his 64 member crew sailed out of Copenhagen Harbour on two Danish naval vessels, Enhiorningen (The Unicorn), which was a frigate, and Lamprenen (The Lamprey), which was a sloop. The latter was crewed by just 16 men, an indication of its small size and the daring of those who sailed aboard it into the vastness of the Arctic.

The first mistake Munk made was anticipating a short summer voyage to Hudson Bay and the opening of the Northwest Passage, so his ships were stocked accordingly and no winter clothing was provided for the sailors. Surprisingly, Munk believed that Arctic conditions did not exist in Hudson Bay.

“Towards the end of June 1619, Munk’s small two-ship flotilla sighted Greenland,” wrote Carlsen. “Cape Farewell was recognized by one of the Englishmen aboard, William Gordon. From then on he seems to have been relying on Hudson’s chart, which was no doubt in Munk’s possession ... it is clear from his diary that he should enter Hudson Strait at 65° Latitude North. North America was sighted on 8th July. They went wrongly into Frobisher Bay.”

But Muck realized his mistake and turned into the strait at the south-eastern point of Resolution Island. He named the cape, Munkenes, after himself.

Carlsen wrote that Munk had many encounters with ice blocking his way and sailed along the south coast of Baffin Island before entering the strait proper on July 17. He renamed Hudson Strait, Fretum Christian, but was unable to proceed as the strait was blocked with ice. Munk found shelter at what he called Rensund. It was there that Munk and his men had their one and only encounter with the indigenous people, which turned out to be a friendly meeting, unlike those experienced by some earlier explorers. They shot caribou and exchanged knives and pieces of iron with the Inuit for seal meat and birds.

Travelling further west into Hudson Strait, they turned south which was another mistake as they sailed into the dead-end of Ungava Bay. On August 20, they were back in the strait, but had lost 10 days, which in the Arctic at that time of year can be quite deadly.

But Munk was undeterred and resolved to proceed in his quest for Hudson Bay and the Northwest Passage.

“What held up the spirit of the commander and the crew was no doubt the assumption that after the passage of Hudson Strait the course would be more southerly, and they would soon be on well-known latitudes, hopefully with a climate similar to that of Scandinavia” (Carlsen).

It was another mistaken belief, as Scandinavia is blessed by being in contact with the warmth-giving Gulf Stream, while the area where he was sailing was instead chilled by the cold Labrador Current. The contrary effects of the two currents were unknown to Europeans of the period. Being on a similar latitude to Scandinavia simply didn’t translate into enjoying a warmer climate while in Hudson Bay.

In early September, Munk explored the Digges Islands, which are now in the territory of Nunavut. The two islands, West Digges and East Digges, are located in Digges Sound, an arm of Hudson Bay, where the strong currents of the bay meet Hudson Strait.

Entering Hudson Bay, he renamed it, Novum Marum, and set a southerly course.

On September 7, facing the onslaught of a violent northeasterly storm, the two ships were separated. On the frigate, Munk fought his way into the mouth of what is now called the Churchill River and found a safe anchorage for The Unicorn (the river and harbour were named in 1686 after John Churchill, the Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company). The smaller Lamprey was lured to the location two days later by smoke and fire signals.

(Next week: part 2)