Among the National Trust of Canada’s 12th annual Top-10 Endangered Places List are the “rural icons vanishing from the landscape” — that is, wooden grain elevators.

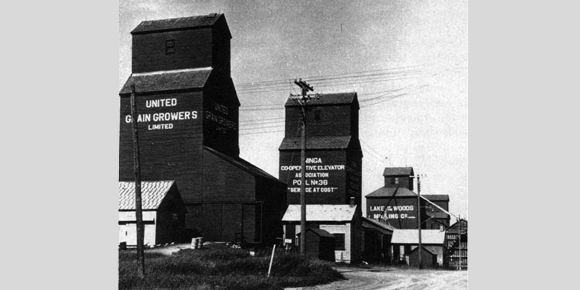

In answering the question of why they matter, the trust in a press release said: “Wooden grain elevators are deeply engrained in Canada’s farming heritage. Once, nearly 6,000 dotted the country, a common sight entrenched in the cultural landscapes of rural Canada. In the Prairie Provinces, in particular, these iconic structures form an integral part of local identity, symbols of farming life.”

But changing technology has rendered the wooden structures obsolete, and they are being torn down at an alarming rate. “Today,” the trust announced, “less than 14 per cent of wooden grain elevators still stand and among them, only 23 have received heritage designation.”

But there was a time when the image of wooden elevators were indelibly etched into people’s minds — a tall unbending sentinel stretching skyward abruptly emerging at the edge of a wheat field whose grain-laden heads bowed before the wind. It was the only large structure to break the monotony of the ocean of grain. Its whiteness or deep red offered a stark contrast to the golden ripening wheat or the yellow of canola flowers. On the side facing on-coming railway traffic, large black, block letters, proudly proclaimed the community it served.

For decades, the country elevator has been synonymous with the prairies. But, it’s symptomatic of our times that bigger is better, and the wood-crib-style country elevator is being replaced by concrete high-volume, high-throughput elevators in central locations. Still, the country elevator is deeply entrenched in the history of the Prairies, harkening back to a time when wheat was king, and farmers called it “prairie gold.” And if wheat was king on the prairies, grain elevators stood over the golden domain as the symbolic guardians of its monarchy.

The elevators have been called by various symbolic names, such as “castles of the New World,” “prairie giants,” “Gibraltars of the prairies,” “towers of silence,” and “silent sentinels of the prairies.”

The traditional wooden elevators owe their origin to an era when the first attempts were made to turn the prairies into a commercially-viable grain-growing region. The farmers in the fledgling province of Manitoba made their first shipment of wheat to an eastern market in 1876. It wasn’t much — a mere 857 bushels — but it was the harbinger of large-scale shipments to the four corners of the globe. The grain trade really took off when the CPR’s transcontinental railway arrived and an all-Canadian route for the export of grain arose.

It was in this period that the ubiquitous grain elevators that came to symbolize the Prairie landscape got their start. At first, they were little more than temporary storage sheds. The first elevator in Western Canada was built in 1879 in Niverville, Manitoba, and was a round structure.

The first square elevator was reputed to have been built in 1881 by A.W. Ogilvie & Company in Gretna, Manitoba, and was patterned after similar American structures. “This type utilized an endless cup conveyor, known as a leg, to raise the grain, which was dumped into a pit from the farmer’s wagon, to bins from which it could be more easily loaded by spouts and gravity into boxcars, placed alongside the building” (Small Farmers, Big Business, and the Battle over the “Prairie Sentinel,” by Karen Nicholson, Manitoba History, Spring/Summer 2003).

The elevators were initially built about 16 kilometres apart to accommodate the travel of a single farmer’s wagon to the elevator and return to the farm over the course of a day. The wagons were weighed in a driveway on a scale before the grain was dumped into the front pit and then re-weighed after being emptied to determine the weight of the grain delivered.

Flat warehouses at first outnumbered elevators. In 1890, there were 90 elevators and 103 warehouses — which were significantly cheaper to build than elevators — at 63 delivery points in Manitoba and the North-West Territories (today’s Saskatchewan and Alberta, which didn’t become provinces until 1905). By 1899, there were 41 elevators and 116 warehouses at 192 delivery points.

The typical flat warehouse could hold approximately 4,000 bushels of grain, while the elevators built to standards set by the CPR had a minimum capacity of 25,000 bushels.

In 1899, of the 447 elevators in the West, 256 were owned by three large companies, 95 by two milling companies and only 146 by independent local millers, grain dealers or groups of farmers (The Country Elevator in the Canadian West, by William Clifford Clark, 1916).

In 1901, the North-West Elevator Association, which was closely linked to the Winnipeg Grain Exchange, controlled two-thirds of the elevators on the prairies. Farmers believed the association acted as a monopoly, keeping prices artificially low.

Provincial governments atempted to break the private monopolies by establishing so-called public elevators, but this turned into an utter failure. While the experiment wasn’t overly successful, it did provide an initial model and object lesson for non-private ownership of grain elevators, such as the pools that came into vogue in the 1920s.

By 1928, the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool operated 900 country elevators, the United Grain Growers (UGG) had over 4,000, while the largest private company, the Alberta Pacific Grain Company Limited, had only 363 licensed elevators. In the 1933-34 crop year, there were 5,901 licensed country elevators, but from this point on their numbers began to decline, although capacity increased to almost 400-million bushels by 1970-71.

The decline of the rural elevator also marked the overall decline of many small agricultural-based communities. Typically, a community’s railway branch line would be abandoned by a railway and then the elevator would fall into disuse.

At Inglis, Manitoba, population about 200 people, restoration of a row of five elevators, the last remaining example of its kind on the prairies, is ongoing. Plaques have been erected designating them a National Historic Site and a Manitoba Heritage Site.

Another plaque recognizes the $100,000 donation by the Murphy Foundation to complete the restoration of two former Reliance Grain Company elevators on the site. Other financial support has been received by the Thomas Sill Foundation, corporations and foundations, as well as private individuals.

But there is still a nagging sadness that not enough is being done to save those rural icons that remain.

As the National Trust for Canada said in its press release, “While some have been saved through creative new uses, every year more and more of these rural landmarks are lost forever.”