by Bruce Cherney (part 1)

The Grey Cup, the prize emblematic of Canadian football supremacy, which will be played on November 29 in Winnipeg this year, has had a storied and occasionally controversial history.

The feel-good story this year is that a team which has only been in the Canadian Football League (CFL) for two short seasons has earned a berth in the November classic. Last year, the Ottawa RedBlacks had a lowly 2-16 record, but under the guidance of 40-year-old quarterback Henry Burris the team made a dramatic turnaround, sporting a 12-6 regular season record and then went on to beat the Hamilton Tiger-Cats in the Eastern Final 35-28.

The RedBlacks will meet the Edmonton Eskimos in the championship game. The Eskimos were victors over the Calgary Stampeders, 45-31, in the Western Final.

The last time an Ottawa team faced Edmonton was in 1981, with the Rough Riders losing to the Eskimos in the title game.

The Grey Cup was originally to be a prize for hockey prowess, but Sir H. Montagu Allan had beat Lord Earl Grey, the Governor General of Canada, to the punch. The Allan Cup would come to symbolize excellence in amateur hockey. Faced with this dilemma, Grey had the next option of making his cup available for supremacy in amateur rugby-football.

Perhaps because of his receiving what he perceived as the next best thing in amateur sports in Canada, the governor general put the commissioning of the new cup in the back of his mind. Two weeks before the championship game, he had to be reminded that a cup was to be made available to the winner. Yet, no one had placed an order with a silversmith, so the University of Toronto, the winners of the first Grey Cup, had to wait a few months before they had the actual cup in their hands.

And, when they received the cup valued at $48 from Lord Grey, the university side was surprised to see that a plaque on its base proclaimed the Hamilton Tigers the 1908 Canadian football champions, even though the idea of a championship cup had only come about in 1909.

The trustees of the cup recognized the plaque as invalid but decided to do nothing about it.

This was just one of many misadventures for the Grey Cup and the championship game.

In 1947, the Grey Cup was nearly destroyed by fire while on display at the Toronto Argonaut Rowing Club. It was slightly tarnished, but it survived.

Edmonton players have been quite hard on the cup. In 1987, it was broken when a celebrating Eskimo sat on it. Tape held the neck in place until it was won by the Toronto Argonauts in 1991. It was again broken when Edmonton player Blake Dermott headbutted it.

On February 16, 1970, the Toronto police contacted Greg Fulton, then secretary-treasurer of the Canadian Football League, and reported a strange call they had received. The caller told the police to go to a telephone booth at the corner of Parliament and Dundas streets in Cabbagetown, Toronto, and look in a coin-return box. The caller said the key would fit a locker in the Royal York Hotel and in the locker would be the Grey Cup, which had gone missing on December 20, 1969, from Lansdowne Park where the Grey Cup champion Ottawa Rough Riders had brought the cup for display.

The trophy had gone from Montreal to Ottawa to Toronto. The first two stages of its journey were planned, but the last wasn’t. Fortunately, despite the CFL’s refusal to ransom the cup, the instructions given by the mystery caller led to the recovery of the Grey Cup.

The cup has also on many occasions been accidentally left behind by victorious teams and later recovered. In 1984, after a team celebration, Bombers’ general manager Paul Robson returned to Winnipeg Arena to find the forlorn cup sitting on a table at centre ice.

The early history of the Grey Cup was tumultuous because the teams that won it tried to keep it in their grasp by hook or by crook. The University of Toronto won the cup in 1909, 1910 and 1911, and then decided they wouldn’t relinquish the Grey Cup until someone else beat them in the championship game. The problem was that the Toronto side didn’t make it to the championship game for the next two seasons. The Varsity team eventually gave the cup to the Toronto Argonauts after they were defeated by them in the 1914 final.

Western teams had their own set of problems with the winners from Eastern Canada, often involving the rules of the game.

Until changes were made in its early days, football in Canada was a hybrid of rugby and what would become true Canadian football. In football’s initial incarnation, there was 14-men per side and the ball wasn’t snapped back to the quarterback, it was heeled back just as in a rugby scrum. The western teams at first played under their own set of rules, which invariably conflicted with those used in the east.

Between the two world wars, the conflict in rules led to protest and controversy. Unfortunately for western teams, the powers behind football in the east were dominant and opposed at nearly every turn the progressions in the game coming out of Western Canada.

From 1924 to 1944, there were seven all-eastern finals, the West being denied a chance to play for the cup because of so-called rule infractions or mishaps.

Until 1921, only eastern teams competed for the cup, but Edmonton in 1921 and 1922 and Regina the following year couldn’t defeat their eastern counterparts.

In 1924, the Winnipeg Victorias were the new great hope from the West. Although they won the right to represent the West, the Victorias never boarded a team to head east because no one could agree on which rail company to use. Most of the executive of the club worked for Canadian Pacific Railway and naturally felt this line should be used since they had free passes. The players, who worked for Canadian National Railways, wanted to use their favourite carrier since they had free passes. Nothing could be resolved so the players offered to pay their own way, but the team executive declared the renegade players could not use the Victorias name nor its colours.

An agreement was eventually reached between the feuding sides, but the ruling body in the east said, “Sorry, too late.” In the end, Queen’s University beat Toronto Balmy Beach in an all-eastern Grey Cup final. This marked a cornerstone in Canadian football history, since it was the last time a university side won the Grey Cup, although they remained in competition for the cup until 1935.

Because of the controversy, Winnipeg’s first Grey Cup jaunt was in 1925 when the Winnipeg Tammany Tigers were clobbered by the Ottawa Senators 24-1.

In 1926, the Regina Roughriders were the western champs but declined to head east, one of the reasons being they didn’t want to wait around for an eastern winner to be declared. As a result, Ottawa won for the second year in a row, this time defeating the University of Toronto 10-7. Regina declined the eastern journey again in 1927, but headed to the Grey Cup for the next four years in a row, losing each time to eastern teams.

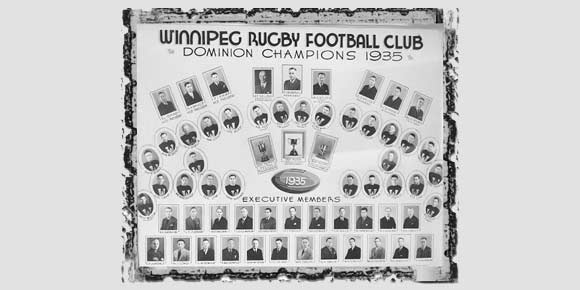

It wasn’t until 1935 that a Western champ would emerge victorious, a milestone in Canadian football history. Over a decade ago, Bruce Kidd called the 1935 final No. 13 in his top-20 list of sporting events for the 20th century in a National Post article. “The Grey Cup really became a national championship when the West joined up and became competitive,” said Kidd. “That win was a symbolic coming of age for Western Canada.”

Up until 1935, Regina had been beaten seven times, Edmonton twice and Winnipeg once by their eastern rivals.

That December 7 was a chilly day in Hamilton when the Winnipeg Winnipegs, or ’Pegs, stepped onto the field. It was raining steadily and the field was a mess of mud. But, the team was ready and it was stacked with great talent, made all the better by seven new imports, including player (quarterback) coach Bob Fritz from Fargo, North Dakota; Russ Rebholz from Wisconsin; Herb Peschel from Long Island, New York; Rosy Adelman from California; Dave Narding from Sarnia, Ontario; and stellar halfback Fritz “Golden Ghost” Hanson, a native of Perham, Minnesota, who had played college football for North Dakota State.

According to Vince Leah, who wrote, A History of the Winnipeg Blue Bombers, the team had to wait nearly a month for the eastern champion to be decided. The ’Pegs opted to travel to Detroit to prepare for the game and avoid Hamilton Tiger spies. Leah, who was inducted posthumously into the WinnipegREALTORS®-established Citizens Hall of Fame and was a well-respected local sportswriter and amateur coach, said the Tigers believed they would defeat the ’Pegs in a cakewalk.

The Tigers and their eastern fans were in disbelief when the ’Pegs left the field at the half leading 12-4.

In the second half, Hamilton pulled within two, after which Hanson picked up a kick on the Winnipeg 32.

“A ring of downfield tacklers converged on Hanson,” wrote Leah, “skidding to a stop on the icy gridiron to prevent a no-yards penalty. Before the defence knew what had happened Hanson burst through the middle and raced for a touchdown.”

The final score was Winnipeg 18, Hamilton 12. Although statistics weren’t officially kept, sportswriters estimated Hanson alone contributed 300 yards in offence.

The eastern-controlled Canadian Rugby Union, the governing body for the Grey Cup and Canadian football of the era, didn’t like what they saw in 1935, so it ruled for the next Grey Cup that no player would be allowed to compete unless he had lived in Canada for at least a year and had taken up residence in the city he was playing for by October 1. Although the CRU said the rule was to protect Canadian players, the western teams knew it was because of the power they gained with the addition of a few imports on each team.

For the 1936 season, the western champion Regina side had five players that were ineligible under the new rules. Regina announced it wouldn’t be going east without its imports but had a change of heart and said it would leave the five imports at home.

Again, it was too late, the Western Canada Rugby Union had withdrawn the challenge and decided to send Winnipeg (they volunteered to go) in the place of Regina. The controversy continued to the point that the West once again didn’t send a champion east to vie for the Grey Cup.

(Next week: part 2)