by Bruce Cherney (part 4)

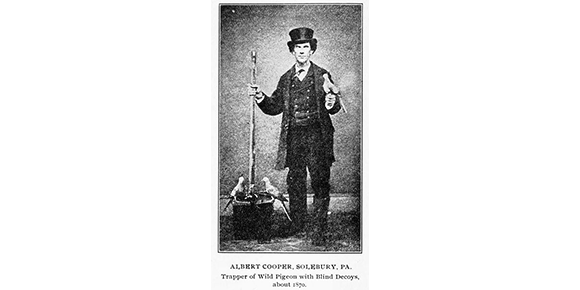

An April 5, 1882, Weekly Wisconsin article — it’s quite an inhumane description by today’s standards — stated the stool pigeon was a bird with its eyes intentionally sewn shut (to keep it calm) and perched on a limb above a salt lick (a strong attraction for pigeons). “A string is attached to its leg and when the hunter pulls the twine, the bird begins to flutter, attracting wild pigeons as they fly over. When enough pigeons land, the trap-net is sprung.

“The birds are killed by crushing their skulls between the forefinger and thumb. They are then shipped to eastern markets after cutting off the wings and pulling the tail feathers.”

In other cases, the blinded pigeon was placed on a stump (stool — hence the name) around which grain — sometimes soaked in whiskey to disorient the birds — was strewn.

Live pigeons were in high demand for trapshooting. In what can only be described as a barbarous act, the live birds were launched into the air to be shot as so-called sport.

A.W. “Bill” Schorger (The Passenger Pigeon: Its Natural History and Extinction, 1955) reported that 20,000 birds were slaughtered at one trapshooting event in Syracuse, New York, in 1877.

It was only when passenger pigeons became scarce that inanimate clay pigeons were mechanically launched into the air as targets for trapshooters.

The pigeons nested in large colonies where the adults were shot or netted, young squabs were knocked out of their nests with long sticks, and pots of burning sulphur were placed under roosting trees in order that the fumes would stun the birds so that they fell to the ground. In some instances, entire nesting sites were put to the torch to harvest the birds.

And it wasn’t just at nesting sites that the pigeons were slaughtered, as professional hunters chased them all year-round wherever they roosted — from the southern to northern range of their migration route and back again. If anything, the birds were becoming overly stressed by the constant assaults on their formations.

The problem for the pigeons was that they tasted too good. Pigeons were eaten fresh, pickled, salted, boiled and baked. Most pigeon pot pie had three cleaned legs, visibly upright in the centre and baked into the crust to show dinners the savoury delight that lay inside. Usually, six pigeons were in each pie.

Pigeon fat was rendered into soap and their feathers stuffed pillows. The thousands left over from a commercial hunt were left for pigs to eat and grow fat on.

For the early settlers, passenger pigeons were “free food on the fly” and a welcomed relief after suffering through a harsh winter and dwindling supplies.

At the largest nesting sites, their sheer numbers dictated that their descent from flight was a riot of destruction. The first to land were often crushed by the mass of latecomers. Limbs creaked and sometimes broke from failing to bear the weight of too many birds. Even trees tumbled to the ground from the burden they couldn’t withstand. Underneath the trees, droppings turned the ground white to a depth of several centimetres.

It was the very fact that the pigeons virtually destroyed their nesting site (later with the additional help of men using axes and fire) of one year that another nesting site at a different location was needed for the following breeding season.

Their nests were hastily-made affairs composed of twigs padded by feathers. The makeshift nature of the nests were seemingly a response to their never-ending need to be on the move.

“The places where the birds are nesting are interesting spots to visit,” wrote Eugene Pericles (Dr. Morris Gibbs) in Nesting Habits of the Passenger Pigeon, from The Oölogist, 1894. “Both parents incubate and the scene is animated as the birds fly about in all directions. However, as the bulk of the birds must fly to quite a distance from an immense rookery to find food, it necessarily follows that the main flocks arrive and depart evening and morning. Then the crush is often terrific and the air is fairly alive with birds. The rush of their thousands of wings makes a mighty noise like the sound of a stiff breeze through the trees.”

A nesting passenger pigeon female laid only a single egg (some early observers claimed two eggs with only one youngster being raised, but the concensus is just one egg). If the egg was lost, it was possible for the pigeon to lay a replacement egg within a week.

A.W. Schorger noted in the spring of 1876, before their nests were completed in the cedar swamp of Crooked River, Michigan, a flock numbered at one billion encountered a snow storm that caused the birds to drop millions of eggs on the frozen ground. “After the storm abated and the snow melted, part of the swamp was still white, the eggs being so thick for several miles as to give the appearance of a snow-covered ground. These birds moved around for a week or two, roosting at night near those nesting, then built for themselves close by the others, and raised their young as if nothing had happened.”

The very fact that a female passenger pigeon laid just one egg at a time in a nest was another reason that disruption by commercial hunters was so disastrous to the survival of the species.

George Atkinson, in his article, A Review-History of the Passenger Pigeon of Manitoba, 1905, cited a letter from J.H. Fleming of Toronto, that the disruption was so constant that the birds had to flee further afield “in search of a congenial environment.”

Fleming wrote that “persistent persecution” depleted even the smallest of roosting sites.

The incubation period of an egg was 12 to 14 days with both parents taking turns when incubating the egg. Upon hatching, both parents fed the hatchling. The squab was fed crop milk — often referrer to as “pigeon milk” — exclusively for the first three or four days, which was rich and fatty and led to the nestling quickly putting on weight. Because the squabs (squab is a Scandinavian word meaning “fat flesh”) were so plump, fat laden and tasty when cooked at this stage, they were prized by commercial pigeon hunters.

The parents flew off and abandoned the youngster after about 14 days. The young pigeons shortly afterward intentionally dropped from the nests to the ground in a vain attempt find their parents. It took a few more days for the young pigeon to fledge and fly from the nesting site. The young birds were ready to breed the following spring.

(Next week: part 5)