Puns have a rotten reputation. Even crossword puzzles sneer at this form of wordplay. One common crossword clue is, “Response to a pun.” The five-letter answer is, “groan.”

Why should this be?

Blame it on well-meaning language reformers. Some 50 years following Shakespeare’s death in 1616, a push to reform education arose. The movement’s aim was to make English clearer and easier to understand. This led to the belief that cleaning up English meant ridding it of such figurative devices as synonyms, metaphors, idioms, and wordplay — including puns.

English satirist, John Eachard (1636-1697) suggested, “Punning, Quibling, and that which they call Jaquing” ought to be omitted from academic studies. Jacqueries were historical dramas with exaggerated operatic plots. Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) expressed “great contempt for that species of wit.”

Victorian editors seldom included all meanings of words in language works published. This all added up to a very low opinion of the pun as well as most other kinds of wordplay.

Everyone’s heard, “The pun is the lowest form of humour,” a quip attributed to American author, actor and comedian, Oscar Levant (1906-72). But there’s more than that in what Levant said. Here’s the complete quotation: “The pun is the lowest form of humor — when you don’t think of it first.”

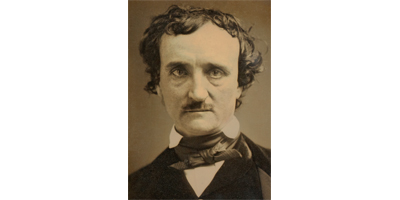

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) said something similar: “Of puns it has been said that those who most dislike them are those who are less able to utter them.”

Before Levant expressed his opinion, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), in 1917, labeled the pun, “The lowest form of wit.”

Levant, Freud, Johnson and other nay-sayers are at odds with some highly esteemed lovers of this type of wordplay — Charles Lamb and William Shakespeare among them.

More than 3,000 puns are found in Shakespeare’s plays. Probably the best-known of these appears in Romeo and Juliet, Act 3, where the dying Mercutio makes a pun with his next-to-last breath: “Ask for me tomorrow, and you shall find me a grave man.”

Asked how his plays were doing, James Barrie (1860-1937), author of Peter Pan, replied, “Some peter out; others pan out.”

Julian Huxley, zoologist brother of Aldous Huxley, once used the phrase, “the aristocracy of genes.”

“You mean blue jeans?” Aldous asked.

Most people don’t think of John Diefenbaker (1895-1979) as a humourist, but even he made puns. Invited to officially open the South Saskatchewan River Dam, he reluctantly agreed saying, “I can always ask my political opponents to drop in.”

Pun (from 1662) has an obscure origin. It is used as both a noun and a verb. The OED defines the verb form as, “To make puns; to play on words.” The noun, pun, is, “The use of a word in such a way as to suggest two or more meanings; to play on words; to use two or more words of the same sound with different meanings to produce a humorous effect.”

If you like puns and need to defend yourself because you like them, just say, “If the pun is good enough for Shakespeare, it’s good enough for me.”