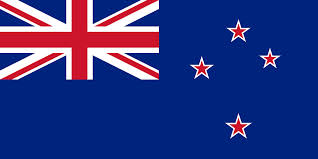

In his arguments to reinvent the New Zealand flag, Prime Minister John Key has invoked the example of Canada’s Maple Leaf Flag.

“Back in 1965, Canada changed its flag from one that, like ours, also had the Union Jack in the corner, and replaced it with a striking symbol of modern Canada that all of us recognize and can identify today,” said the prime minister in a speech about his proposal.

“Fifty years on, I can’t imagine many Canadians would, if asked, choose to go back to the old flag. That old flag represented Canada as it was once, rather than as it is now. Similarly, I think our flag represents us as we were once, rather than we are now.”

Key is in favour of dropping the Union Jack and the stars of Southern Constellation (people often confuse the New Zealand and Australia flags because they both sport the same theme) and inserting a silver fern on a black background. The silver fern is a national symbol popularized by New Zealand’s national All Blacks rugby team.

While it’s true that it would be difficult today to find many Canadians willing to give up the Maple Leaf for the Red Ensign, New Zealand is now encountering the same “Flag Flap” that we endured when the proposal was made in 1964 to change our national flag. In New Zealand, those who are for and those against the flag change are roughly divided in half, as was the case in Canada in 1964-65. But reading blogs accompanying newspaper articles on Key’s proposal, the more vocal group is against the change (also the case in Canada).

When Canadian Prime Minister Lester Pearson announced his intention to create a new flag on May 17, 1964, at a national convention of the Royal Canadian Legion in Winnipeg, it was a brave, though some would argue foolhardy, location to argue for a new flag.

When Pearson said, “I believe that today a flag designed around the Maple Leaf, will symbolize and be a true reflection of the new Canada,” the veterans booed him. The legionnaires had fought under the Red Ensign with the Union Jack in the upper corner during the Second World War, and firmly believed it should remain the flag of Canada.

It is the same argument being made today by New Zealanders about Key’s proposal to remove the Union Jack from his nation’s flag.

Pearson smiled to reporters after his Winnipeg speech, and said the angry crowd had not bothered him, quoting former U.S. President Harry Truman, who had said, “If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.”

“Pearson was probably more determined to go forward after that meeting, because he saw that the thing had been politicized and that people had worked on these people, or they’d worked on themselves, to sort of divide the nation into old and new, and he thought this was wrong,” said Jim Coutts, a Pearson government staffer.

The flag debate had indeed been politicized, especially by John Diefenbaker and his followers. The Conservative Leader of the Opposition didn’t like Pearson and didn’t like his flag.

“I think they loathed each other,” observed Coutts. “There’s no question about that. I think Diefenbaker loathed Pearson because be beat him (in the 1963 federal election). In retaliation, he went after Pearson personally.”

Diefenbaker announced that the new flag would be passed “over his dead body. Flags cannot be imposed, the sacred symbols of a people’s hopes and aspirations, by the simple, capricious, personal choice of a Prime Minister of Canada.” Diefenbaker went on to compare the proposed new flag to a beer bottle label, and called it a “sop” to Quebec.

Gordon Churchill, one of Diefenbaker’s strongest backers, referred to Pearson in abusive terms, calling him “a sawdust Caesar ... trying to force the country to accept his personal choice of flag.”

Churchill said the Maple Leaf design was a “monstrosity.” Diefenbaker further contemptuously referred to the flag design as the “Pearson pennant.”

The Pearson pennant was actually a flag with three red maples leaves with two blue border stripes. With so much animosity arising, Pearson decided to remove himself from the “Flag Flap,” and have an all-party committee come up with a new design.

Dr. George F.G. Stanley, the dean of arts and head of the history department of the Royal Military College of Canada, told the committee that Canada had the right to adopt the flag of its choice. It was Stanley’s suggestions that led to the Maple Leaf flag, which was based on the Royal Military College of Canada flag.

The maple leaf was worn by Canada’s Olympic athletes in 1904. Canadian soldiers during the First World War had maple leaves embossed on their jacket buttons. Canadian war graves of both world wars had a single maple leaf carved into their headstones.

On December 14, 1964, Conservative MP Paul Martineau from Quebec, gave one of the better speeches of the debate, saying: “The maple leaf is a true Canadian symbol. Canadians recognize it as such anywhere, and others recognize us as Canadians by the maple leaf symbol ... The new flag is the symbol of the future because it expresses unity, that unity to which so many of us have paid lip service during the course of this debate ... I believe this maple leaf will express for Canadians, in their own undemonstrative and taciturn way, the firm conviction that Canadians want to live together, work together, and build a worthwhile nation.”

Following the committee’s recommendation, the Canadian Parliament eventually passed an act making the Maple Leaf design now flying across Canada the national flag.

About 10,000 people gathered on February 15, 1965, to witness the raising of the Maple Leaf over the Peace Tower on Parliament Hill. It was a cold, gray day, but when the flag was raised by Joseph Secours, a 26-year-old RCMP constable, and a 21-gun salute rang out, the sky opened up, the sun shone through and an obliging breeze caused it to wave boldly in the wind.

Jim Rae of the Ottawa Citizen wrote, “Emotions that had been pent up for more than an hour emptied in a mighty cheer just as the Maple Leaf reached the top of the mast for the first time.”

Diefenbaker looked downcast and dabbed at his eyes with a handkerchief as he shed tears when the Red Ensign, which had acted as the national flag, was lowered to make way for the new flag.

But adverse opinions were in the minority on the Hill that day.

“If our nation, by God’s grace, endures a thousand years, this day ... will always be remembered as a milestone in Canada’s national progress,” proclaimed Pearson. “It is impossible for me not to be deeply moved on such an occasion, or to be insensible to the honour and privilege of taking part in it.”

Be warned, New Zealand, that the Canadian example so often cited by Key shows that it’s not always easy to redesign a national flag, but it is indeed possible, and an easily-identifiable and unique flag, such as the Maple Leaf, does instill a greater sense of national pride.