by Bruce Cherney (part 6)

By December, Juba was suggesting that federal assistance for a new city hall would be a possibility if it was built on the existing Main Street site.

“He is known to fear that if Broadway is abandoned a new city hall would never be built,” Dafoe added.

At the time, seven possible sites were being investigated by the planning research centre of the school of architecture at the University of Manitoba, headed by Professor John Russell (Free Press, December 6, 1960).

Juba now believed that the construction of the new city hall at Main Street would be the first phase of downtown urban renewal.

The university team eventually named the St. Paul College site on Ellice Avenue as the most favourable for a new city hall. Russell said it was “at least twice as good” as any of the other locations, reported the February 15, 1961, Free Press.

Russell also said the Main Street site was the “sentimental” favourite among the seven proposed locations for the new city hall.

It was projected that it would cost the city $968,600 to purchase the St. Paul College site. However, the site would also have to include all the area bounded by Ellice Avenue, Balmoral Street, Qu’Appelle Avenue and Kennedy Street.

In the end, the University of Manitoba site recommendation was ignored. On March 20, 1961, city council decided to build the new city hall on the existing Main Street site.

The city then received $800,000 from the provincial government for the sale of the Broadway site. In 1962, the formerly city-owned land, as well as a section of provincial property (the original University of Manitoba campus) were combined to form Memorial Park.

At the same meeting, the name of the “city hall project” was changed to the “Civic Centre project.”

Of course, Premier Roblin said he was glad that the city hall would be built on the existing site, adding that the civic centre would be part of the overall redevelopment of the district.

At the time, there was some speculation that an interesting legal battle might have ensued if council had decided to use another site, because of the terms of the Ross property sale to the city in 1875 for the nominal fee of $600.

Two days after the site change, Juba announced that the architectural design would be similar to the original proposal for the abandoned Broadway site. Architect Leslie Russell, of Green Blankstein Russell and Associates, presented the design for the new city hall to council on June 16.

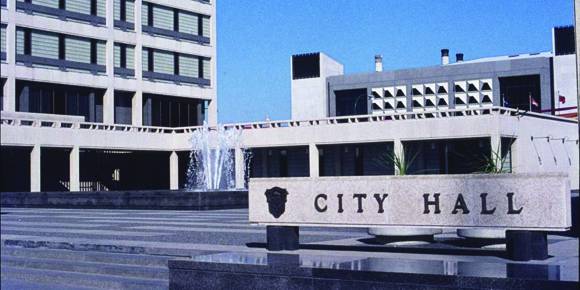

The plan showed a rectangular two-storey city hall separated by a landscaped plaza from a U-shaped, six-storey administrative area.

Meanwhile, the cost to build the new city hall had risen from $6 million (the amount approved by ratepayers in 1956 that the city could borrow for the project) to just over $8 million, according to a financial report released by Juba.

When it turned into a Civic Centre, the new cost was estimated to be $9.2 million. To raise the additional funds, a proposal was made to sell city properties. It was believed that $2.3 million could be raised by converting city-owned property on the west side of King Street into a parking lot.

On February 19, 1962, city council held its last meeting at the old city hall in preparation of its demolition, which began in March. Until the new Civic Centre was completed, council would be meeting in the “old school board offices” at the corner of William Avenue and Ellen Street. Administrative offices were set up in temporary quarters on King Street.

The demolition of the old city hall was completed by May 31, 1962.

Juba said that G.A. Baert Construction Company Ltd. of St. Boniface was ready to commence work when given the go ahead. In its winning bid, the construction company indicated it would complete the project by October 31, 1964.

The architects who designed the new Civic Centre called it “utilitarian” and a “simple” structure. It was an extensive redesign of the original Broadway plan in order to accommodate the smaller Main Street site.

The $8.2-million Civic Centre —

a 21⁄2-storey council building and a seven-storey administrative building — officially opened on October 5, 1964, with 1,000 people attending. Those interviewed by newspapers expressed mixed reviews about the new Civic Centre, with some applauding its design and others muttering their displeasure.

Over the years, Winnipeggers have developed a love-hate relationship for the Civic Centre architecture.

Juba said at the opening: “This centre is not a monument for the dead or a tomb for the living, but it is meant to be the centre of a dynamic and growing city and a place that in years to come can be looked at by children, our children’s children, and they will say ‘they built wisely.’”

Soon after, the new city hall was named the ugliest building in Canada, and called a tribute to Soviet nationalist architecture of the 1920s — a replica of Lenin’s Tomb.

Theodore Maloff, an assistant professor of architecture at the University of Manitoba, said its vast frozen porridge of limestone “reflects a democracy that distrusts itself.”

Yet, a New York publication, Progressive Architecture, praised the design as being better than the original proposed for the Broadway site.

“We are particularly interested in city hall designs and similar project designs where there is a competition,” Burton Holmes, the managing editor of the New York magazine, told Free Press columnist Alan Rach (published August 10, 1965). “We try to herald designs whenever we can.”

According to the magazine article, “All things considered, it seems as if Green Blankstein Russell Associates produced a better design on the new site than they would have on the original site with their competition-winning proposal.”

G.I. Russell of the winning architectural firm, told Rach they were “disappointed that we could not build the original design ... but we are quite satisfied with the Main Street design.”

In particular, he said the interior setup “functions and works well.”

But when the 600 workers began working in the administrative building, the staff complained about overcrowding. That was a problem, since the new building was meant to replace the cramped administrative offices in the former “gingerbread” city hall.

Still, the actual construction of a new city hall was a long-anticipated accomplishment. It took 60 years of debate and acrimony, but it was finally built.