by Bruce Cherney (part 2)

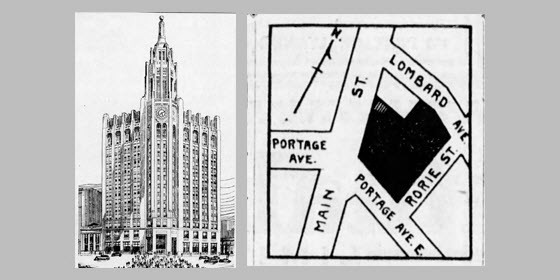

Incorporated into the plan for the new James Richardson & Sons skyscraper on the northeast corner of Portage and Main was the two-storey stock and bond investment branch of the company, established in 1927.

“The facade of the present building will not be changed, but the new building which is to be erected around the present structure will harmonize with it” (Winnipeg Tribune, July 19, 1929).

The skyscraper was to occupy the entire northeast corner of Portage and Main, between Rorie and Lombard streets, with the exception of the portion along Lombard occupied by the Merchants Bank, which was at the corner of Main and Lombard.

All the existing buildings that were not part of the final plan for the skyscraper were to be demolished.

The new Richardson building was expected to cost about $2 million, although later estimates called for $3 million to be spent on its construction.

The building was projected to be 300 feet (91.4 metres) high, nearly twice as tall as the next highest office building in Winnipeg, which was the 164-foot (50-metre) high Union Bank Building/Royal Tower, the structure noted as Winnipeg’s first steel-frame and reinforced concrete skyscraper. The 10-storey building was completed in 1904. It is the oldest surviving skyscraper in the nation and was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1996.

In an August 31, 1929, Tribune article that listed the highest structures in the city, it was stated that the famous Golden Boy atop the Manitoba Legislative Building rose 242 feet (73.76 metres) above the ground, while the Fort Garry Hotel was 194 feet (59.13 metres) above street level. Next in height was the Union Bank Building along Main Street, while the fourth tallest was the McArthur Building with its cornice 159 feet (48.5 metres) above Portage Avenue. The Royal Bank Building at the corner of Main and William stood 148.5 feet (45.3 metres) tall and the Winnipeg Electric Building on Notre Dame Avenue was slightily less than a metre shorter less.

“However, in vertical height from the street line the increase (of the Richardson Building) is not by any means a radical departure,” claimed the July 27 Tribune. “This vertical height will not go beyond 14 storeys, or two storeys higher than some of our present edifices.

“After rising for 14 storeys from the street line the Richardson Building will be set back some feet and three more storeys added, making 17 storeys in all.”

Actually, the original announcement of a 17-storey edifice was later revised to 16 storeys. An October 22 article in the Tribune mentioned that the building at the northeast corner of Portage and Main would be one storey less, since a 13th storey was considered an “ill-omen,” which was “so deeply rooted that architects and engineers will take it into consideration by leaving it out of Winnipeg’s latest addition to the downtown business section.”

The newspaper stated the set back was also a Richardson decision made for architectural effect.

The set back also conformed to the Winnipeg Building By-Law that limited the height of any building to one and a half times the width of the widest street on which it abutted. The greatest width was along Main Street at 132 feet (40.2 metres) from the street line, which gave a maximum allowable vertical height of 192 feet (58.5 metres), as calculated by the newspaper.

“Buildings may be built higher than this,” according to the Tribune article, “but if so, they must be set back one foot for every three feet of additional height. Towers placed on buildings must not occupy more than 15 per cent of the area of the first floor.”

With the restrictions, the newspaper stated that Winnipeg’s skyline faced no danger of having skyscrapers of the magnitude of New York’s or Chicago’s, which created downtown canyons between the tall buildings. The two American cities had skyscrapers that were multiple-storeys higher than the proposed Richardson building.

For example, the Singer Tower in Manhattan, completed in 1908 (demolished in the 1960s), had 47-storeys. Another Manhattan landmark, the Empire State Building, an Art Deco-style skyscraper, was completed in 1931 and rises to a lofty 102-storeys.

Mayor Daniel McLean said the enterprise shown by the Richardsons in proposing to build the skyscraper was encouraging from a civic standpoint.

Work was reported to have begun on the new building in the October 12, 1929, Winnipeg Free Press.

William Carter, the president of Carter-Halls-Aldinger Company, the contractor hired to construct the skyscraper, told the newspaper that his workmen were razing structures on the site to make way for the new building. First to be demolished was the old seven-storey Toronto Trust Company building.

A high fence was built around the demolition site to ensure the safety of the public.

“When the buildings are demolished and the site cleared, both on Main and Lombard streets (the exception being the Merchant’s Bank Building at the northwest corner of Main and Lombard), caissons will be sunk and the excavation for the foundation started ...

“Caisson work will be started early in December. These caissons will go down to an average depth of 52 feet (15.84 metres), which it has been decided is sufficiently far below the surface of Main street to support this huge structure. Mr. Carter hopes to have the building ready for occupancy one year from the present time.”

The 400-foot (122-metre) frontage of the building was to be set at a wide angle along Main Street and Portage Avenue East, which was originally called Thistle Street.

Work had begun, but there was a problem in the form of the October 29, 1929, stock market crash, otherwise known as Black Tuesday.

Wall Street Lays an Egg was the headline on that day in Variety.

As stock dropped precipitously, margins were being called. Thousands found they couldn’t put up enough cash to pay their margins, which is borrowed money from a broker to purchase stock, and their assets were liquidated. Essentially, they were wiped out financially. The money had been borrowed in the expectation that the stock would rise in value and could be sold for a profit, but when the market went bust, stock values rapidly declined instead of going upward.

In Toronto and Montreal, 525,000 shares were liquidated. Margin traders joined their New York counterparts in suffering the effects of the crash.

On the Prairies, the market collapse was compounded by a failure to sell wheat on a glutted world market. Much of the 1928 bumper crop could not be sold.

In Manitoba, wheat was still king and the linchpin of the local economy. Farmers could get credit during the boom times of the Roarin’ 20s, but when wheat prices fell in 1929, the rule of thumb was foreclosures and evictions when they couldn’t meet their loan repayments.

Manitoba farmers lost up to 50 per cent of their income as the Great Depression rolled along.

The worldwide Great Depression was the result of many factors: shaky foreign government finances; debt incurred by Allied governments during the First World War; unsustainable reparation payments imposed on Germany; and protectionist tariffs adopted by countries supposedly to help their domestic economies, which hit Canada particularly hard because it relied on foreign trade, especially for manufactured goods and commodities such as grain.

Since James Richardson & Sons was heavily into the wheat market, the company was facing its own difficulties due to the onset of the Great Depression.

“Until the business outlook in Canada shows a promise of more rapid expansion” said James Richardson in a November 19, 1929, press release. “I have decided to discontinue work in connection with the building we proposed to erect at the corner of Portage and Main. The work of the architects in connection with the plans and specifications, which will take some months to complete, will in the meantime be proceeded with.”

Richardson said he was still going ahead with ordering the material for the building (Free Press, November 20). Three days later, the same newspaper reported the work stoppage was temporary.

In the meantime, the only evidence of a skyscraper was to be built was a massive hole in the ground.

All hope of the new building proceeding ended when the Free Press reported on March 31, 1930, that work had started to fill in the excavation site.

(Next week: part 3)