by Bruce Cherney (part 1)

At the time of his appearance at the Kirkfield Park Race Track, during the ninth annual race meet hosted by the Winnipeg Automobile Club on Labour Day 1912, Barney Oldfield was recognized as the most popular automobile racer in North America.

“Barney (born Berna Eli Oldfield in 1878 in Wauseon, Ohio) was ‘of the people,’ and the public identified with him as they identified with no other driver of his time,” wrote William F. Nolan in his 1961 biography of Oldfield. “From his gaudy ties to his barroom brawls, he was a ‘regular guy.’ Win or lose, he was (the public’s) true speed idol, and no one else, and when he raced it was as though they watched themselves out on the track at speed.”

Oldfield, who usually posed for photos with a cigar clamped between his teeth — after breaking a couple of teeth in a racing accident, he used a cigar to prevent breaking more teeth as his cars bumped and rattled around the track — was scheduled to attempt to break both the one-mile (a mile equals 1.6 kilometres) and two-mile speed records at the track in west Winnipeg, as well as participate in a five-mile match race against automobile circuit teammate Lew Heinemann. Oldfield was scheduled to drive a V-4 300-horse power front-wheel-drive Christie car when attempting the new speed records, but would be at the wheel of a Cino when taking on Heinemann in his Prince Henry Benz.

Oldfield was known as the first racer to drive a car at 60 mph — a mile in 60 seconds — which was a feat he accomplished on June 20, 1903, at the Indiana State Fairgrounds. After setting the record, he became known as the “mile-a-minute man.” At Daytona Beach, Florida, on March 16, 1910, in his car named Blitzen Benz, Oldfield set a world speed record of 131.724 mph.

“It doesn't thrill me a bit to drive a 1:05 clip, and though I might win races without having to drive under the minute, I just have to let it out to get another thrill (Barney Oldfield, interviewed in Automobile, August 1, 1903).

“You just clamp your teeth on your cigar and get down to your work so that you know to an inch how much the car will swing on the turns, and you get more fun out of the ride than a whole stand full of people.

“I haven’t any mania for speed, and I don't lose my head and do the mad-man act or anything like that, but I do like to feel the car jump and feel the power of being able to guide the machine so nicely, no matter how quick the turns come.”

Early auto meets were based on the horse racing model of having eight or 10 races on the day of the event, and the Kirkfield Park track meet in 1912 was no different.

A handicap auto race over a 10-mile course was slated between Oldfield and Heinemann. It was expected that several local drivers would participate in this race. In six events scheduled, including the 25-mile Dunlop Cup, only racers from Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and Manitoba were eligible to compete. The races involving Oldfield and his teammates were deemed professional events, although anyone could enter the open five-mile and 10-mile handicap race for cars with engines not exceeding 450 cubic inches to take on the Oldfield team.

Joining the two U.S. racers on the team during their “barnstorming” stop in Winnipeg was fellow countryman, “Wild” Bill Fritsch. The team, referred to as “The Speed Kings,” was managed by Homer C. George, who organized with W.A. Emmett, the manager of the Winnipeg Automobile Club, to have Oldfield and company participate at the Kirkfield Park track.

Oldfield’s teammates would invariably ease up on the throttle towards the end of races to allow the public’s “hero” racer to win. Still, an unforseen incident did cause Oldfield to lose a race in Winnipeg, but that result was probably part of the barnstorming act.

“Oldfield padded his reputation by adding an element of drama to these events by losing the first match, barely winning the second, and after theatrical tweaking and cajoling of his engine, winning the third match,” according to a Henry Ford Museum article about Oldfield. (In 1902, Oldfield purchased the race car dubbed 999 that was built by Henry Ford.)

The participation of the renowned racing team was not out of the goodness of their hearts, but to claim appearance fees.

“A celebrity in every sense of the word, Oldfield could command as much as $4,000 per appearance, owned a fleet of cars and even traveled the country in a custom-built rail coach,” wrote Kurt Ernst for Hemmings Classic Car in 2013. “Though excluded from ‘proper’ racing for much of his career, Oldfield managed to successfully convert his notoriety into cash.”

The contract Oldfield signed to participate in Winnipeg, according to the August 10, 1912, Free Press, stated “that Barney must lower the track record before being eligible to any share of the gate, so that it is certain that some fine speed work will have to be accomplished by Barney and his big Christie before he gets level on his contract. As it turned out, Oldfield got paid, since he lowered the one-mile track record by 4.8 seconds to 54 seconds.

“Oldfield is also willing to wager the sum of $2,000 that he will beat the time made by any other driver that the club can bring against him from any country under the sun.”

Such touring racers as Oldfield were sponsored by automobile and tire companies that wanted to promote their products. In return, the racers received a salary plus expenses and a car of their choice. Oldfield was sponsored by automobile manufacturer Christie for four years (Walter Christie lost money sponsoring Oldfield and his car division was never successful) and by the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company for many years.

Because Oldfield took part in unsanctioned races and events, he was labelled an “outlaw” and became engaged in a running feud with the American Automobile Association, which periodically resulted in being fined and suspended from taking part in AAA sanctioned races. Due to AAA bans, Oldfield only made two Indianapolis 500 appearances, finishing in fourth and fifth place.

“It is confidently expected that the Gas Power Age trophy will pass into new hands this year,” predicted the August 31, 1912, Manitoba Free Press, “and some seconds will be clipped from (W.C.) Power’s (one mile) record of 59 1-5 (59.2 seconds, accomplished in a Christie). His time of 25 minutes 19 1-5 seconds for 25 miles in the Dunlop trophy race of 1910 is also likely to be lowered by at least two or even three of the cars entered in this classic event, and Billy Rogers and his Ford car will have to do some tall hustling to keep possession of the trophy that Rogers secured last year.”

(See KIRKFIELD, page 6)

The August 10, 1912, Free Press predicted that Oldfield would drive his car over one mile “as low as 50 seconds.”

“The arrangements made by the (Winnipeg) club ensure one of the best race meets ever held in Canada and racing fans will be certain of some real racing when the big men get together in the various events.”

The Kirkfield Park track wasn’t exclusively used for automobile racing, but also for motorcycle and horse races, all of which were popular spectator sports at the turn of the 20th century. While horse racing had existed for thousands of years, both auto and motorcycle races were the new crowd pleasers, and drivers and spectators became obsessed with the pursuit of speed.

In the case of auto racing, the cars were noisy machines that were little than a frame with four wheels, a steering wheel, seat and a powerful engine for the era. Motorcycle racing was equally primitive with racers stripping their machines down to the basics in the pursuit of speed — no fenders, clutch, brakes or exhaust. Among the famous motorcyclists of the day using the Kirkfield track was “Wild” Joseph “Joe” Baribeau, a local speed demon who held the world speed record timed over a 100-mile course.

It was even suggested that Oldfield should race Baribeau during the Labour Day meet at the Kirkfield track in 1912. But Oldfield told newspaper reporters that it was very dangerous to race motorcycles and cars together. If the two vehicles ran into each other, the motorcycle racer would invariably be the loser, he said.

Still, Oldfield told the Manitoba Free Press (published August 24, 1912) that he was perfectly willing to match his 300-hp Christie against a motorcycle in a speed trial at any distance between one and five miles.

Winnipeg Automobile Club manager A.C. Emmett — he also was the auto section editor for the Free Press — tried to arrange the clash between car and motorcycle, but his attempt proved futile.

The Kirkfield Park dirt race track was where the Heritage Park residential neighbourhood is now located. When the gates at the entrance of Heritage Park off Ness Avenue were installed in 1963, a plaque was attached that read: “To Barney Oldfield and the old-time drivers who thrilled Winnipeg when Heritage Park was an auto race track, these gates are respectfully dedicated.”

Brothers Roderick “Rod” J. and Alex MacKenzie had made plans as early as 1899 to build a horse racing track at the site named after their hometown of Kirkfield, Ontario. Rod was a horse racing enthusiast and an early president of the Manitoba Jockey Club. But construction at the site didn’t get underway until 1905. A year later, Alex died and Rod become the sole proprietor of the property.

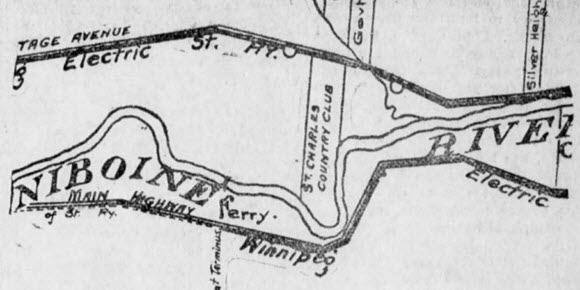

Kirkfield Park consisted of 318 acres with a frontage on Portage Avenue of nearly half a mile, according to a report in the May 30, 1908, Free Press. The site ran back from Portage and Sturgeon Creek flowed through the central section of the property. The location was deemed advantageous as it provided “excellent drainage for the whole grounds.”

The actual entrance to the race track was off today’s Ness Avenue. The Winnipeg Electric Railway Company provided streetcar service along Portage Avenue to near the race track. The CPR provided special train service from Winnipeg on event days on its line that passed the track. Eventually, streetcar service was extended to the track by a spur line running from Portage Avenue.

The August 25, 1905, Free Press contained an article outlining MacKenzie’s plans for the Kirkfield site, which he promised would be host to a first-class horse track with honest outcomes for all races.

“One thing you may depend on,” he told the reporter, “is that none of the cheap gambling element will be associated in this enterprise. The betting ring has practically controlled the racing here of late years, and honest races have been few and far better. An incident of the loose manner in which turf matters were run was shown at the last exhibition meet, when the entire bookmaking privileges were sold to one man, thus preventing any competition.”

In effect, without competition, the bookie was able to dictate the odds of every race to his advantage.

MacKenzie said the completed one-mile course was to be oval shaped with a quarter mile on each stretch and quarter mile turns on either end. A workout track was to be placed in the centre of the course. The grandstand would hold 4,000 spectators, and seating would be increased when demand dictated its expansion.

In 1905, a Mr. Sawin from Boston was engaged by MacKenzie to built a one-mile race course. In the fall, work on the track began. Before the work could be completed, Sawin died, and “it became necessary to secure the services of a new expert. After considerable inquiry, the services of Mr. Charles W. Leavitt, Jr., of New York city, were enlisted” (Winnipeg Tribune, May 29, 1908).

(Next week: part 2)