by Bruce Cherney (part 3)

After the Canadian success at Passchendaele, Captain Christopher O’Kelly wrote his mother (reprinted in the Manitoba Free Press, June 14, 1918): “We were in a big attack and made a great success. The commander-in-chief and the divisional commander said that our battalion did the finest work that any battalion has ever done in France, and the colonel told me that my company did the best work of any company in the battalion. My company captured 150 Germans and 12 machine guns. We were right in the thick of the notorious ‘pill-boxes.’ It was a glorious fight. I got some dandy souvenirs out of the attack. A couple of dandy German revolvers, one of which I gave to a brother officer. I have a dandy for myself. I also got an alarm watch from a German officer and a dagger. We sent the first batch of 100 prisoners without getting a single souvenir from them, as we were too busy getting the situation cleared up.”

What his letter home failed to mention was the hell that was Passchendaele, which claimed 16,000 Canadian casualties, as was predicted before the battle by Canadian Commander General Arthur Currie.

The Canadians held the battlefield and on November 14, British troops took over the Canadian lines.

Speaking about Passchendaele in December 1917, British Prime Minister Lloyd George remarked to C.P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian and a political ally, that: “If people really knew (about the casualties), the war would be stopped tomorrow. But, of course, they don’t know, and can’t know.”

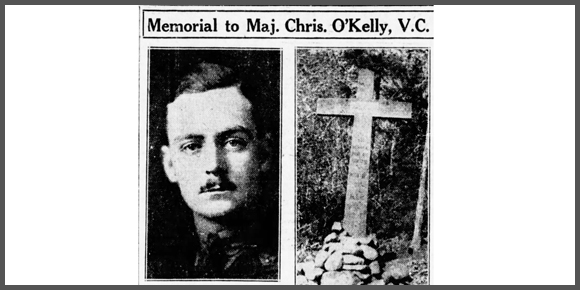

O’Kelly was presented his VC by King George V on March 25, 1918, at Buckingham Palace.

When O’Kelly returned home to Winnipeg in April 1918 for a visit, he was greeted as the grandest of heroes. The April 11, 1916, Winnipeg Tribune reported that more people were at the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) Station to welcome O’Kelly home “than ever turned out to the arrival of a train load of returning soldiers.”

At the time, O’Kelly was the first member of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) to return home with a VC.

“When the train in the large station was packed to suffocation and a thousand or more, unable to get inside, were standing outside waiting for a glimpse of Winnipeg’s greatest war hero.”

On the train platform were his father, Christopher, and sister, Monica. His other sister, Margaret, was with his mother, Cecilia, while she was being treated at a hospital at Battle Creek, Michigan. It was on his mother’s account that he applied for and received a three-month-long furlough. When he arrived in Winnipeg, a telegram informed O’Kelly that his mother was recovering from her illness.

When questioned about his exploits on the battlefield at the Fort Garry Hotel by a Tribune reporter, O’Kelly replied, “I merely did my duty, that’s all. Anyone else would have done the same under the circumstances.”

On April 15, 1918, a public reception under the auspices of the Catholic Club was held for O’Kelly at Columbus Hall, 255 Smith St.

In his opening remarks, J.H. O’Connor, the chairman for the event, said, “There is, I think, veritable magic in the name of Christopher Peter O’Kelly.”

“Captain O’Kelly,” said Archbishop Alfred Sinnott, “you are welcomed home. You are a thousand times welcomed. There is not a home in the city where would not be welcomed. You are welcomed as one of the great lads who have gone forth in the great cause” (Free Press, April 15, 1918).

The archbishop said that the Catholic Church, of which O’Kelly was a member, was proud of him, as were the people of Winnipeg.

“In the hour of danger the state has the absolute right to demand of us the best service it is in our power to give. In a very short time you are going to return to your comrades in arms. When you go back to them, what message will take back to them? Will you tell them that their fellow citizens at home will stand behind them to the end — until the gigantic task for which we entered the war has been accomplished?”

O’Kelly replied in a modest manner to all the praise heaped upon him.

“I thank you. But what I have done is but a trifle of what our Canadian boys in France have done and are still doing. The spirit of the boys is something the Hun can never beat. Words of mine can never express my admiration for the boy who goes out in the defence of his country. This is the first speech I ever made. I feel like a new sentry on duty at the front for the first time.”

(Next week: part 4)