by Bruce Cherney (part 6 of 6)

The alleged friend of William Farr, the prisoner facing charges in the Manitoba Court of Assizes in November 1895, including arson and the attempted murder of his wife and four children, who signed his name in a letter received by the Manitoba Free Press, as “J.A.C,” wrote that the police were bearing false witness against Farr.

“I am going to say its (sic) all very well for the people of Winnipeg to think he was living a double life but let me say that is not true, for I know everything and I promised him never to mention anything but I cannot stand what I have read now ...”

The letter writer said Farr had told Margaret Robertson that he was married and had a wife and family to provide for and could not give her money whenever she asked, although he did periodically give her some funds out of sympathy.

The writer alleged that Robertson was constantly lying and Farr wanted her behind bars. “I am of the opinion she knows some thing about the fire, as she has told lady frends (sic) and my own sister that she wanted Farr’s family out of existance (sic) ...,” he wrote.

The next letter claimed to be written by someone who had only seen Farr from afar. He wrote that Farr was innocent and he was the guilty party. The writer, who signed as “J. Macr---D,” said he regretted what he had done and had set the fire to cover up a bungled burglary at the Farr family’s Ross Avenue home.

Of course, the prosecution introduced expert witnesses to give testimony in court that pointed to Farr penning both letters, despite attempts being made to disguise the handwriting and the use of numerous misspellings, which they judged to be done deliberately to hide that the letters were written by the defendant.

During a cross-examination of Robertson by N.F. Hagel, who along with Horace Crawford was Farr’s attorney, she was asked why, with the preponderance of evidence presented in court saying otherwise, did she still believe Farr was unmarried?

“I certainly believed — he was not married.”

Hagel told the jury in his closing statement that the trial had created more interest than any trial since he came to Manitoba, and that they were to start their deliberations under the premise that the defendant was not guilty. He said the evidence was mostly circumstantial and it was the job of the prosecution to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt.

Hagel told the jury the deed of arson was definitely done by someone, but the prosecution had to prove that it was done by Farr, not the other way around.

Hagel said the letters showed that Farr was put in a situation of “thraldom” by Robertson, who used her “ripe, over-ripe charms,” and, “thinking he was a snap clung to him with feline tenacity.”

At length, he described Farr’s fall to that of the biblical Samson and Delilah, and that she was playing his client in a similar manner to Delilah inducing Samson to have his hair cut so that he could be captured by the Philistines.

Hagel said Robertson was a clever woman who knew Farr was married and simply strung him along to her advantage.

The defence attorney then attempted to shift the blame for the arson to Robertson. He claimed that she had the most likely motive for the crime, which was to keep Farr under her control by eliminating his wife and children.

Hagel told the jury that the only crime Farr was guilty of was “unfaithfulness,” which wasn’t the crime he was charged with, nor was it punishable with prison time.

Crown prosecutor Hector M. Howell — the other prosecutor was H.A. McLean — also gave a lengthy closing statement to the jury, saying in summation that he had provided a “great mass of evidence” that proved Farr’s guilt.

Farr’s jail break was also considered to be an admission of guilt by Howell, as was the “confession letter,” to the Free Press, alleged to be in Farr’s own handwriting.

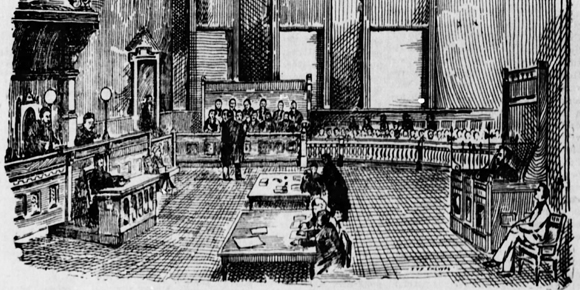

The jury retired at 5:10 p.m. on November 12 to consider the evidence and after just an hour of deliberations, they were prepared to present their verdict.

Their deliberations were so brief that Howell and Crawford had to be called by telephone at their homes to immediately return to the courthouse.

“It was noticed that every juryman looked straight in front of him into vacancy,” reported the Tribune on November 13, 1895. “No man turned to scrutinize the prisoner, it was noted as an ominous sign for him. They wore the air of men who had made up their minds to do their duty, however unpleasant.”

Jury foreman Henry Butcher pronounced the verdict of “guilty.”

Farr was described as shrinking perceptibly into the corner of the defendant’s box, and “evidently suffering great mental pain, was led down the stairs to the jail.”

Farr was convicted on all counts — arson with intent to kill and murder, intent to injure the landlord of the building and defrauding the insurance company.

He was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment in Stony Mountain Penitentiary on November 18, 1895. In a lengthy address after the guilty verdict and prior to sentencing, Farr said he was being sent down the river for a crime he didn’t commit, but the judge told him that he had received a fair trial and then pronounced the prison term. He further ruled against the defendant having a new trial.

“Public interest in the case has been absorbing since April 13st last, when it burst like a bombshell on the startled minds of our citizens ...,” commented the Free Press on the sentencing of Farr in a November 20 front-page article. “The manner in which the crime was fastened upon Wm. Farr and the cleverness with which the police picked up the scattered links of evidence were most credible to our local police officers, and the subsequent work of the deputy attorney-general (Howell) in preparing the case for trial was so thoroughly done as to warrant the public reposing full confidence in the skill and capacity of the law officers of the Crown in ferreting out crime and bringing the criminals to justice.”

According to the newspaper, “Thus ends the last act in a most remarkable drama of real life — will there yet be an epilogue before the final curtain falls?”

Even with her husband’s sentencing, Ellen Farr believed him to be an innocent man, who was completely incapable of committing such a horrendous crime against her and their children, despite all the evidence saying otherwise, as well as his proven infidelity. It was her reinterpretation of the age-old cry of protest, “I was framed!” into, “He was framed!”

How Farr managed to convince one woman to firmly believe he wasn’t married and another that he was innocent of plotting her death reveals the extent to which the man was able to charm his way through life; that is, until he was forced to confront a jury of his peers, who saw through his veneer of projected victimization through the ill will of others, especially the police.

George Ham wrote in his autobiography, Reminiscences of a Raconteur, that Farr served five years of his sentence and after his release took up residence on the West Coast. “The young woman (Robertson) subsequently married a farmer and lived for a number of years in the vicinity of Glenella.”