by Bruce Cherney (part 3)

E.W.J. Hayes, the city’s chief health inspector, visited the Coronation Block at the corner of King and Alexander and reported that the building was in reasonably good condition, although the state of the rooms left much to be desired.

He said some tenants had resided in the block for long periods of time. Among them were two railway workers, which showed that not all the tenants were unemployed transients.

Newspapers reported that all the victims of wood alcohol poisoning at the Coronation were familiar to police, having each appeared in court on several occasions.

The block was also infamous for wood alcohol (methyl hydrate or methanol) poisoning deaths with 25 such cases recorded by city police over the years, according to the December 29, 1927, Winnipeg Tribune.

The Winnipeg Free Press on the same day reported that the Coronation Block was so noted for the consumption of “dynamite” (wood alcohol, which is also called methanol, methyl hydrate or methyl alcohol) and “canned heat” (Sterno) that its tenants commonly referred to the building as the “Chemical” block.

At a January 4, 1928, inquest into the death of Timothy Curran, who was a member of the doomed drinking party, 30 witnesses were called, some of whom were residents of the Coronation Block.

One witness, J. Beaumont, who knew all the deceased, said they were habitual drinkers of the “poison,” which is colourless and odourless. Methanol is the simplest form of alcohol. It is closely related to ethanol, the type of alcohol normally found in beer, wine and spirits, but much more toxic.

Wheatley, who recovered from the effects of drinking wood alcohol at the Coronation, said that he entered one room where he found several men in possession of a bottle of methyl hydrate. He took a few swigs and shortly afterward became ill. He went outside for some fresh air, returned to the building and laid down, but was soon after rushed to hospital, suffering from the effects of his ill-advised consumption of the poisonous brew. Drinking just two to eight ounces of methyl hydrate can cause death in an adult.

He told the inquest that he had on several occasions bought wood alcohol from the Sun Drug Store on Main Street, including many bottles in a single day that he always took to the Coronation Block to be drunk.

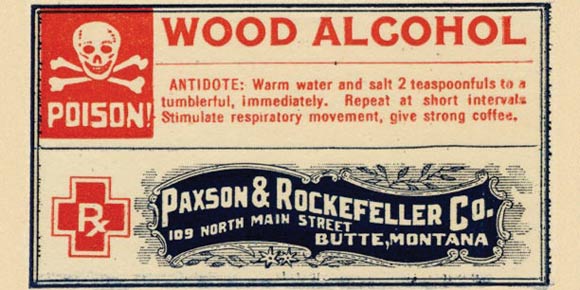

Winnipeg detective B.A. Kilcup confirmed Wheatley’s assertion about the source of the wood alcohol, testifying that he removed two 12-ounce bottles of from a room in the Coronation and both bore the label of the Sun Drug Store, 530 Main St. “They had on them the words, ‘Methyl Hydrate, Poison,’ and a skull and cross bones’” (Tribune, January 5).

After finding the two bottles, detective Kilcup went to the Main Street drug store and purchased a similar bottle for 35-cents, and “had no trouble getting it.”

C.M. Teeple, the owner of the drug store, pointed out during the inquest that there was no restriction on the sale of methyl hydrate, “and the only reason he could see for his large business in this product was the fact that so many of the men who drank it frequented that locality and his store was convenient for them” (Free Press, January 5, 1928).

The druggist claimed that the sale of wood alcohol in his store was strictly supervised.

A.W. Blackie, a city chemist, analyzed a bottle recovered from room 19 in the Coronation and found it to contain 76-per-cent methyl hydrate (twice as much wood alcohol as Canadian government regulations required) with the remainder being commercial ethyl (grain) alcohol.

Teeple said this was unusual as normally the proportions were reversed.

Teeple said he purchased all such products from the National Drug and Chemical Company and there was no way to determine what the exact proportion of grain or wood alcohol was received in the chemical company’s casks. After buying the product in bulk, druggists poured the mixture directly from the casks into bottles, which were then appropriately labelled as poison.

Since there were no restrictions on the sale of methyl hydrate, Winnipeg police admitted they could make no arrests following the poisoning deaths of the 11 men and the blinding of another.

Hague testified that he had issued a notice “that all the dilapidated beds, furniture and floor coverings would have to be replaced ... (at the Coronation),” as reported in the Free Press on January 5.

Hague testified at the inquest that in each of the 34 rooms for rent, the number of beds varied: one room had five beds and in the others there could be four, three, two or even one bed.

He judged 32 of the beds to be unfit (Tribune, January 5).

Dr. H.M. Cameron, the provincial coroner in charge of the inquest, said he had visited the Coronation Block and found it to be in the most disgraceful condition, with the bedding being unfit for human use and expressed the opinion that the city should exercise greater control over such establishments.

Detective Blackie described the block as “the dirtiest hole I have ever been in.”

(Next week: part 4)