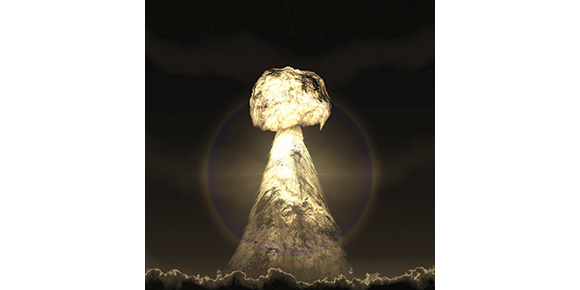

When the first atomic bomb was detonated in a tower above the sands of a New Mexico desert on July 16, 1945, physicist and leader of the Allied team that built the device, Robert Oppenheimer, expressed the gravity of what had occurred by quoting scripture from the Bhagavad Gita, “Now I have become death, the destroyer of words.” Later, he would comment that, with the creation of the earth-shattering weapon, atomic scientists now “know sin.”

On the morning of August 6, 1945, just before 8:15, Col. Paul Tibbetts spied a break in the clouds over his target, leveled the B-29 bomber Enola Gay, released the bomb code-named “Little Boy,” banked sharply and opened the airplane’s throttle. Fifty seconds after its release over Hiroshima, the 20-kiloton atomic bomb exploded, outright killing 80,000 people. Three days later, the citizens of Nagasaki suffered a similar fate. For the first and only time, nuclear weapons had been used to obliterate two cities and their inhabitants.

The A-Bomb could be “a means for World Peace,” wrote U.S. Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, in his diary, or it may be “Frankenstein.”

“I realize the tragic significance of the atomic bomb ... It is an awful responsibility which has come to us ... We thank God that it has come to us, instead of to our enemies; and we pray that He may guide us to use it in His ways and for His purposes,” said U.S. President Harry S. Truman on August 9, 1945.

The release of the two nuclear bombs did bring about a temporary “world peace.” Just as 24,000 Canadians were being shipped to the Pacific Theatre of Operations (PTO), Emperor Hirohito, facing the threat of more destruction (what he didn’t know is that the Americans had run out of A-bombs), announced the surrender of Japan to the Allies, ending the Second World War on August 14, 1945.

In hindsight, many have argued that dropping the “bomb” was unnecessary. But at the time, it was welcomed by those expecting to continue the fight during the invasion of the Japanese homeland — an invasion that was predicted to result in at least 250,000 casualties.

Years ago, I talked to an Royal Air Force (RAF) pilot who had been stationed in the PTO during the war. He was adamant in his belief that dropping the bomb saved thousands of Allies lives and brought the war to a quick end. It is a belief I have heard continually expressed by other veterans.

Six years into the Second World War, it was only fighting men and women who were weary of war, but also politicians and the public. The top policy makers in the U.S. worried about ending the war quickly, not the morality of their decision to drop the bomb.

Canadians, who experienced the horrors of Japanese prisoner of war camps, following the December 1941 debacle at Hong Kong, and then freed from sure death in the camps with the A-bombs’ release, also didn’t consider the morality of the decision. The 42,000 Canadians expected to take part in the invasion of the Japanese homeland, were also grateful that their services were no longer required.

Today, historians have the advantage of access to documents that the Second World Wart fighting troops would never have seen, nor, for that matter, cared about. They were more interested in their survival than the thoughts and actions of their political masters, although they did recognize the overall strength of their cause was the ultimate defeat of the tyranny posed by the Axis powers.

The historical record seems to indicate that the dropping of the bomb may have been unnecessary, as Japan was on the verge of surrender. A strategic bombing survey conducted by the American war department immediately following the war concluded that Japan would have surrendered before November 1 without the use of the bomb.

Japanese cities were being shattered by conventional bombing. General Curtis LeMay of the 20th USAF ordered the methodical destruction of the cities with fire bombing raids. During 10 days in March 1945, 11,600 B-29 sorties had wiped out large sections of Japan’s four largest cities, killing at least 150,000 people and made another million homeless. Yet, the Kamikaze attacks on American ships and the fight to the death battles at Iwo Jima and Okinawa clearly showed that the Japaneses’ will to fight had not been destroyed. In addition, the lessons learned from Nazi Germany showed that the destruction of cities by conventional air attacks did not destroy moral nor the will to continue fighting. It was not until the death of Hitler and the capture of Berlin by Soviet (Russian) troops that Germany surrendered to the Allies.

The morality of dropping the A-bomb on civilians did play on the minds of policy makers. Some of Truman’s advisors even argued for a type of demonstration of the bomb’s destructive power. “It is clear that alternatives to the bomb existed and that Truman and his advisors knew it ... (it) is certain that the very claim the bomb prevented half a million deaths is unsupportable,” wrote J. Samuel Walker, a U.S. government historian with the nuclear regulatory agency in 1990.

In 1978, historians found confirmation in Truman’s diary that surrender had been discussed before the bombing of Hiroshima. Truman wrote of a “telegram from the Jap emperor asking for peace.” The entry came after a cable had been deciphered from Hirohito to the Japanese ambassador in Moscow, asking the Soviets to intervene on behalf of peace talks with the Americans. The only stipulation was that Hirohito be allowed to continue as emperor after the war. “This was a condition, of course, that Truman gave to Japan — after he dropped the bomb,” diplomatic historian and author Kai Bird told a reporter for the Globe and Mail, following the 50th anniversary of the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima.

The reality at the time was that Truman would have been pilloried by the Russians (who declared war on Japan shortly after the cable to the Soviet ambassador) — even the American people — if he tried to make a separate peace with the Japanese. The possibility of peace was so remote at the time that it didn’t come up for discussion during the Potsdam Conference, where Soviet dictator Stalin, Truman and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met to divide up Europe into spheres of influence.

Following the successful testing of the bomb, Truman’s spirits were reported to have picked up, but Stalin simply shrugged when told of the test. Of course, he had spies in New Mexico keeping him informed about any progress made. And when Russia tested its own bomb in 1948, it was the precursor for other nations — stable or otherwise — to join the nuclear club.

The fact that the bomb was used can be seen as a great injustice perpetrated against all of humanity, as the threat of nuclear destruction looms like Damocle’s sword over the head of everyone living on this fragile planet. To this day, its impact reverberates around the globe. The ghosts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki still haunt the world.