by Bruce Cherney (part 5)

James W. Taylor, the U.S. consul in Winnipeg, became involved in attempting to secure the release of the prisoners charged with kidnapping of the so-called Lord Gordon Gordon. With the consul’s participation, the Minnesotans’ imprisonment escalated into an international incident.

On August 4, 1873, the Minneapolis Tribune reported that the case of the Minnesotans confined at Fort Garry was the “subject of earnest consultation in Washington.” The newspaper claimed that the U.S. State Department was working to secure the release of the prisoners.

In a cable to Canadian Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, Manitoba Lieutenant-Governor Alexander Morris said that a “man known as ‘Lord Gordon’ was last night (July 2) kidnapped by some Americans near here, a reward of $10,000 being offered for his apprehension in the United States.” Morris advised Macdonald to avoid becoming embroiled in the incident, but it was too late as international tensions were spiralling out of control.

American Consul Taylor sent a telegram to J.C.B. Jacobs, the Acting Secretary of State in Washington, confirming the arrests and asking for help.

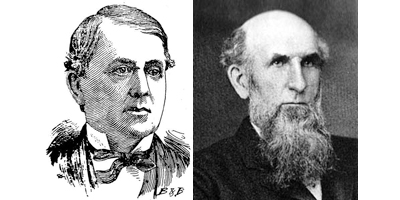

On August 7, the Minneapolis Tribune reported that Minnesota Governor Horace Austin was in communication with Sir Edward Thornton, a British MP visiting Washington, asking for his help in requesting that the Canadian authorities release the prisoners. The British government minister had also been in contact with the state department and the acting secretary of state, according to the newspaper article.

Austin was joined in Washington by Minneapolis Mayor George A. Brackett, both of whom were able to meet with U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant.

According to the records of Brackett, President Grant had authorized the sending of an army north into Manitoba, “if the speedy release of the Minnesotans could not be effected legally ...” (Alexander Begg).

“While it is true that no official action has yet been taken to secure the release of the prisoners, it is also true that individual members of the government are using their personal influence to secure that end (Tribune, August 11). They are seconded by the British Minister, Sir Edward Thornton, as well as the Governor General of Canada (Lord Dufferin), and these gentlemen will be likely to accomplish more in less time than if the matter was confined entirely to official channels.”

“He (Austin) has no doubt of securing the release of the prisoned parties on bail,” reported the Tribune on August 7.

It was initially a forlorn hope as Manitoba Atorney-General Henry J. Clarke announced the defendants had to be held in jail to ensure they were available for trial. Clarke believed the men would flee Manitoba for Minnesota if they were granted bail.

In addition, Macdonald refused to recognize the American argument that it was a question of exercising a “common law” right to seize Gordon using a U.S. warrant. The prime minister said he would only act under the extradition laws between the two countries. Actually, it was a British law “relating to the extradition of criminals” that was specific in the circumstances of issuing and honouring a warrant for arrest and made it extremely difficult to bring fugitives residing in Britain “or Her Majesty’s dominions” charged with a crime in the U.S. to justice in that country (Britain then technically oversaw Canada’s foreign policy, but seldom interfered when Canada interacted with other nations unless there was perceived to be a direct challenge to what was considered to be Britain’s national interests). There were then only seven categories of crimes that allowed for the extradition of an offender to the U.S., and none applied to Gordon. The Chicago Tribune of September 29, 1873, pointed out that “swindlers” were exempt from extradition under the British law.

The terms of the law outlined how a Dominion government proceeded with an extradition, so Macdonald advised Morris not to deal with Minnesota Governor Austin, as communication regarding the case should only be between Ottawa and Washington.

Taylor then went to the press and outlined the details of the American warrant in order to solicit public sympathy for the prisoners.

Attorney-General Clarke told reporters that Taylor’s actions were an attack on Canadian justice, contempt of court and entirely improper. He then telegraphed the Canadian minister of justice to pressure Washington to recall Taylor.

Our People Should Make Ready, read an August 1 headline in the St. Paul Pioneer, which denounced Canadian authorities as corrupt and declared that American officials should not bar the Fenians from again attacking Manitoba. Just two years earlier, Manitobans were sent into a panic by Fenian invaders who had been stopped from entering the province by the intervention of the U.S. Cavalry. That another Fenian raid wouldn’t be curtailed through American intervention at the border was a serious threat that couldn’t be taken lightly.

Minnesota newspapers also called for raising a militia to ride north and rescue the Americans held in the Manitoba jail.

In an August 16, 1873, editorial, the Manitoba Free Press said the “Minnesota press ... seem to have thrown aside all notions of propriety, and common sense (when writing about the Americans arrested for kidnapping). This is the way the case stands: (Loren) Fletcher et al have, in the eyes of Manitoba’s people, committed a grave crime, and no amount of twaddle about common law, and all that, will convince them to the contrary.”

The Free Press said the threat of sending “a horde of ruffians” to Manitoba “does little to advance the cause of the kidnappers or ensure they receive a lenient sentence.”

The Winnipeg newspaper cautioned the press across the border not to “blame the good people of Manitoba for the actions of a man who has been thrust upon them ... don’t accuse us of making a hero of a man who is a fugitive from justice ...”

The behind-the-scenes lobbying eventually paid off as Prime Minister Macdonald and Lord Dufferin intervened, convincing Manitoba officials to review the extraordinary circumstances of the case. At their urging, the five prisoners were released after pleading guilty to kidnapping during a special court convened on September 16. In order to have the special court accepted by the Mantoba authorities and deal once and for all with what had become a thorny international incident, the Canadian government agreed to pay the full cost of the court’s proceedings.

The men received a 24-hour jail sentence from Court of Queen’s Bench Judge Louis Bétourney, which amounted to a mere slap on the wrist for a supposedly heinous crime. The men were then free to return to the U.S.

George Bryce wrote that Francis Evans Cornish, Winnipeg’s first mayor and one of the lawyers hired by Gordon to represent him, went to Headingley in the middle of the night to collect his fee from “his lordship.” Cornish apparently feared that the stories circulating about Gordon were true and he would not be paid.

Bryce related a “humourous account of this midnight adventure” by an unnamed “narrator” in 1873. “The young man who officiates as bodyguard to his lordship (H. Pentland), being called, intimated to Mr. Cornish that he might leave just then in good health, but he (the bodyguard) would not be responsible for any damage to Mr. Cornish’s anatomy in case of delay in vacating.

“Mr. Cornish, in a brief but pointed speech, exhibited to the young man that the latter was much nearer the clutches of the undertaker than he fondly imagined. After some desultory but uncomplimentary palaver, his lordship’s private counsel betook himself and companion to a neighbouring house ...

“Result: Lord Gordon and his aide-de-camp were gone in the morning!

“Nothing has since been heard of the fee!”

“A remarkable fact in connection with this famous incident was that Gordon was indicted at the same assizes (court) as his would-be abductors, on charges of larceny, forgery and perjury,” wrote Alexander Begg.

By this time, Attorney-General Clarke, as well as Manitoba newspapers and locals, were becoming better acquainted with the nefarious deeds of the bogus Lord Gordon.

The impostor aristocrat, who with a silky-smooth tongue and a bogus pedigree had convinced so many to part with their money, hatched another scheme to elude the law, which he sensed was once again uncomfortably reaching out to gather him within its grasp. Thus far, he had escaped answering for his swindles in New York and Toronto, finding what was believed to be a safe refuge in Winnipeg, but his luck was running out. Under the guise of a hunting trip, a pastime he had pursued so often in Manitoba that he was lulled into a false sense of confidence that few would consider it an extraordinary undertaking. The alleged Lord Gordon Gordon planned to shoot his way across the prairies toward the West Coast, but as he set out across the plains, there arose mounting evidence that the so-called peer of the realm came from a less-than-illustrious English parentage.

On September 6, 1873, the Free Press reported Gordon was at Poplar Point “on his way towards the setting sun for ‘shooting’ purposes ...”

The rumour then circulating in Winnipeg was that Gordon was using the hunting trip as a ruse and intended to eventually reach the Pacific Coast where he could catch the proverbial “slow boat to China,” and thwart any attempt to make him accountable for his crimes.

Sensing that Gordon was about to make good his escape, Manitoba Attorney-General Henry Clarke issued a warrant to arrest him “on the charge of stealing an awl worth about one shilling,” according to Alexander Begg (History of the North-West, 1894).

On August 13, 1873, Manitoba Provincial Police (MPP) Chief Richard Power set out to track and capture Gordon, an enterprise that turned into an adventure across the plains. The wanted man’s trail initially took Power to Shoal Lake and Oak Point northwest of Winnipeg, but Gordon was not found heading in that direction. Power was forced to return to Winnipeg for supplies, knowing that the hunt for Gordon would take more time than was originally expected.

(Next week: part 6)