We all know about Remembrance Day, but there is also Indigenous Veterans Day that occurs near the start of Veteran’s Week (Nov.5-11) on November 8.

While exact statistics are difficult to determine, the rate of Indigenous participation in Canada’s military efforts over the years has been impressive. These determined volunteers were often forced to overcome many challenges to serve in uniform, from learning a new language and adapting to cultural differences, to having to travel great distances from their remote communities just to enlist. The challenges they faced often extended to their post-service life.

During the First World War (1914-1918), more than 4,000 Indigenous people served in uniform. Nearly one in three able-bodied men would volunteer. In fact, some communities (like the Head of the Lake Band in British Columbia) saw every man between 20 and 35 years of age enlist.

Skills such as patience, stealth and marksmanship, as they had come from communities where hunting was a cornerstone of daily life, contributed to many of these soldiers becoming successful snipers and reconnaissance scouts, and earned them 50 decorations for bravery. Henry Louis Norwest, a Métis from Alberta and one of the most famous snipers of the entire Canadian Corps, held a divisional sniping record of 115 fatal shots and was awarded the Military Medal and bar for his courage under fire.

When the Second World War erupted in 1939, many Indigenous people again answered the call of duty. By March 1940, more than 100 had volunteered and by the end of the conflict in 1945, over 3,000 First Nations members, as well as an unknown number of Métis, Inuit and other Indigenous recruits, had served in uniform. While some did see action with the Royal Canadian Navy and Royal Canadian Air Force, most would serve in the Canadian Army.

While many again served as snipers and scouts, in this war they also took on interesting new roles. One unique example was being a “code talker.” Men like Charles “Checker” Tomkins of Alberta translated sensitive radio messages into Cree so they could not be understood if they were intercepted by the enemy. Another Cree-speaking “code talker” would then translate the received messages back into English so they could be understood by the intended recipients.

Indigenous service members would receive numerous decorations for bravery during WWII. Willard Bolduc, an Ojibwa airman from Ontario, earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for his brave actions as an air gunner during bombing raids over occupied Europe. Huron Brant, a Mohawk from Ontario, earned the Military Medal for his courage while fighting in Sicily.

Indigenous people also contributed to the war effort on the home front. They donated large amounts of money, clothing and food to worthy causes and also granted the use of portions of their reserve lands to allow for the construction of new airports, rifle ranges and defence installations. The special efforts of First Nations communities in Ontario, Manitoba and British Columbia were also recognized with the awarding of the British Empire Medal to acknowledge their great contributions.

When the Korean War erupted in 1950, several hundred Indigenous people would serve. Many of them had already seen action in WWII which had only come to an end five years earlier.

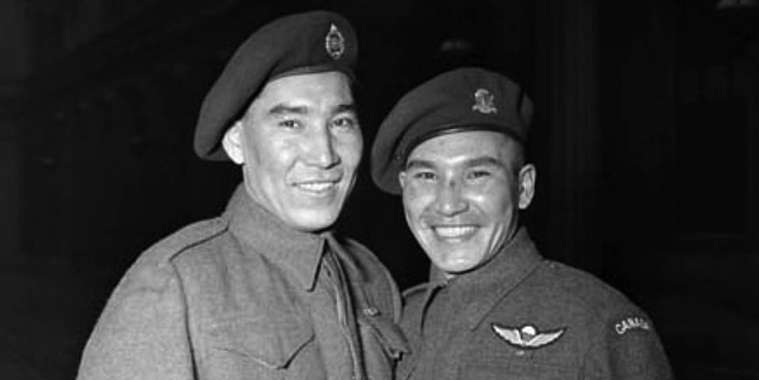

Manitoba’s own Tommy Prince, an Ojibwa and one of Canada’s most decorated Indigenous soldiers, served with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry in Korea. Prince was second-in-command of a rifle platoon and led a group of men into an enemy camp where they captured two machine guns. He also took part in the Battle of Kapyong in April 1951, which saw his battalion awarded the United States Presidential Unit Citation for its distinguished service — a rare honour for a non-American force.

While thousands of Indigenous people proudly served in uniform during the war years, and many Indigenous communities contributed to the war efforts in other ways, there was a dark side to how the Canadian government treated these communities. Canada expropriated hundreds of thousands of acres of reserve lands during this era. Some of their land was also taken and given to non-Indigenous people as part of a program that granted farmland to returning Veterans. The government typically denied this reestablishment program to Indigenous Veterans, and also treated them unfairly in other ways.

Many Indigenous people had hoped their wartime service and sacrifice would increase their rights in Canadian society. But Canada did not treat them the same as other Veterans after they returned to civilian life. Often they were denied access to full Veteran benefits and support programs. Despite serving on the front lines together, Indigenous Veterans were left behind compared to their non-Indigenous comrades. This second-class treatment made their transition to life back home even harder. This discrimination had a negative impact on many brave Indigenous people who had given so much in the cause of peace and freedom.

Despite these challenges, Indigenous men and women have continued to proudly serve in uniform in the post-war years. Like many who pursue a life in the military, they’ve been deployed wherever they’ve been needed — from NATO duties in Europe during the Cold War to service with United Nations and other multinational peace support operations in dozens of countries around the world. In more recent years, many Indigenous Canadian Armed Forces members saw hazardous duty in Afghanistan during our country’s 2001-2014 military efforts in that war-torn land.

Closer to home, Indigenous military personnel have filled a wide variety of roles, including serving with the Canadian Rangers. This group of army reservists is active predominantly in the North, as well as on remote stretches of our east and west coasts. The Rangers use their intimate knowledge of the land there to help maintain a national military presence in these difficult-to-reach areas, monitoring the coastlines and assisting in local rescue operations.

The story of Indigenous service in the First and Second World Wars, the Korean War, and later Canadian Armed Forces efforts is a proud one. While exact numbers are elusive, it has been estimated that as many as 12,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit people served in the great conflicts of the 20th century, with at least 500 of them sadly losing their lives.

This rich heritage has been recognized in many ways. The names given to several Royal Canadian Navy warships over the years, like HMCS Iroquois, Cayuga and Huron, are just one indication of our country’s lasting respect for the contributions of Indigenous Veterans.

This long tradition of military service is also commemorated with the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument in Ottawa. This deeply symbolic memorial features a large bronze eagle at its top, with four men and women from different Indigenous groups from across Canada immediately below. A wolf, bear, bison and caribou — powerful animals that represent “spiritual guides” which have long been seen by Indigenous cultures as important to military success — look out from each corner. Remembrance ceremonies are held at this special monument, including on Indigenous Veterans Day.

Veterans Affairs Canada would like to acknowledge the assistance of Fred Gaffen, whose research was used in the creation of this article.

For the full article and more information visit www.veterans.gc.ca

Visit www.veterans.ca and use their event locator tool to find Remembrance Day ceremonies near you.

Photo credit: Tommy Prince (right), a Manitoba Odjibwa, with a brother. (C.J. Woods / Department of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-142289)