by Bruce Cherney (part 5)

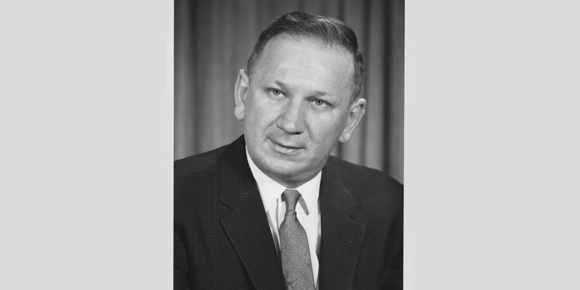

The Conservatives under Duff Roblin ousted Campbell and the Liberal-Progressives after 35 years of political rule in Manitoba. Roblin first formed a minority government in 1958 with help of the CCF (today’s NDP) and then, in the same year, gained a decisive majority government by capturing 36 of 57 seats.

In 1959, Roblin tied urban renewal in Point Douglas to the location of the new city hall site. The premier said his proposal was not about slum clearance, but to be successful required a focus, what he called a “stimulus,” which would be the new city hall.

Of course, this somewhat embarrassed city officials, who agreed with voters that the Broadway site was where the project should be located. Mayor Juba told the premier that such a change would have to go to another referendum. To which, Roblin replied that it might be wise to test public opinion.

When asked why the province was insisting on Point Douglas and also ignoring a possible site west of Main Street, Juba replied: “A number of sites were possible, but we have selected that one, and I think we should settle for it” (Free Press, February 17, 1959).

By December 1959, with the premier still hanging onto the proposal for Point Douglas, the contest for a design for the new city hall had been completed. The local architectural firm of Green Blankstein Russell Associates was awarded the $15,000 prize for what was described in the December 16 Free Press as “a sleek, thin, 10-storey glass-faced structure” along Broadway across from the legislative building. A low two-storey companion building was also part of the firm’s design.

The new city hall was modelled on the “Civic Centre” concept, with one building for council and one for the city administration, separated by a courtyard and connected by an underground walkway.

According to the report by the five judges: “The jury liked the fact that this entry succeeded in expressing both the majestic scale required for an appropriate symbol of government and the human scale that welcomes the citizen in a democratic manner.”

“Under a one-city plan this building could be used without any extra space,” said Juba, “provision has been made for expansion in every department. I was concerned that it should be functional. The design doesn’t matter too much to me, but it’s a lovely design.

“This is an investment that wil pay dividends. It blends well on the site. I think the separation of the elected representatives from the administrative departments is a good idea.”

But the actual “site” selection would continue to be a problem for a few more years.

To complicate matters — and possibly as a sign of frustration with the premier — Juba suggested the new city hall should be built on the grounds of a former slaughterhouse in Elmwood. It was Swift Canadian property that faced a gas works plant and a lumberyard, with a Winnipeg Hydro plant across the Red River.

Of course, strong objections were hear from other members of city council about Juba’s proposal.

On July 25, 1960, city council voted 9-7 to accept the Broadway site. At the meeting, it was agreed to send a letter to Premier Roblin requesting that the Broadway-Osborne site be turned over to the city. The premier expressed regret about the decision, but said he would abide with the wishes of the majority in city council.

“This has been a long, drawn-out question,” said Alderman Crawford. “I have the feeling that this is the last time I will stand before this council to sponsor a proposal in this regard.”

Saul Cherniack was one of the seven aldermen to vote against the motion, saying he wanted the Broadway site to be turned into a park. History would grant his request with the creation of Memorial Park.

“There will never be a new Winnipeg city hall if we don’t go ahead and build on Broadway,” said Alderman David Mulligan. “Mayor Juba’s suggestion of the Elmwood site was made in desperation.”

It was Juba who told the council he would be writing to the premier as soon as possible to obtain the Broadway site, which shows he wasn’t overly sincere about his suggestion of the slaughterhouse property for the new city hall.

Juba was simply taking on his more outrageous personae, typified by the occasion when he erected an outhouse in Memorial Park with a sign declaring it to be, “The deserving office of Hon. Russ Doern.” Juba objected to the Manitoba public works minister’s plan to construct a public washroom in the park.

It would still take time for the final plans for the new city hall to be settled.

Two weeks after the Broadway site was selected by council, the premier had a change of heart, expressing the view that the location would be “a bad move.” In fact, the premier had earlier offered the city $500,000 for urban renewal if it didn’t pursue the Broadway site.

In another surprise move, council passed a motion by a 15-3 vote, which didn’t mention Broadway or another potential site. It merely called for negotiations with the premier to achieve a better financial deal for urban renewal in central Winnipeg.

“Mayor Stephen Juba’s abrupt reversal on the city hall question Tuesday night could produce a new low in relations between the mayor and Premier Duff Roblin,” wrote John Dafoe in the September 10, 1960, Free Press.

Apparently, Juba had earlier promised the premier that he would favour a site for a new city hall other than Broadway if the city received $800,000 from the province for urban renewal. At that point, Juba was still discussing the Elmwood site as an alternative.

“City council turned down the proposal and left provincial officials wondering whether the mayor hadn’t made the implausible Elmwood suggestion as an indirect way of killing the province’s offer without openly opposing it,” wrote Dafoe.

At the council meeting, Dafoe reported that Juba had reversed his stand and said the 1957 referendum accepting the Broadway site was binding.