by Bruce Cherney (part 2)

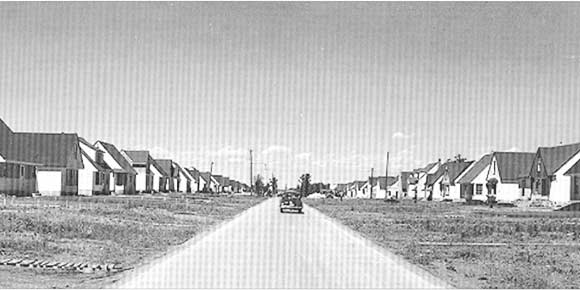

Winnipeg may have been in the midst of a house building boom due to the return of Second World War veterans to “Civvy Street,” but all was not completely well on the housing front. In fact, a low-cost rental housing shortage arose with federal, provincial and municipal governments scrambling to keep up with the crisis. Suburbia was growing, but the downtown core was feeling the effects of overcrowded houses and the lack of new rental units being built to keep up with demand.

Alderman (today’s councillor) Henry “Harry” Scott, the chairman of Winnipeg’s housing committee, forecast a deficit of 18,000 housing units by October 1946 (Winnipeg Free Press, July 23, 1946).

“At present, in Winnipeg there are more than 3,000 applicants for Wartime Houses on hand and about 180 applications for emergency shelter,” reported the newspaper. “All the latter applications are from Winnipeggers with children ...”

One city official commented that the situation was “not improving.”

Emergency housing was provided to 172 families in July 1946.

“Just what could be done in the way of new housing, civic officials would not hazard, but last year, according to federal housing figures, 727 new dwelling units were erected. In 1945 also, 493 new buildings other than dwellings went up in Winnipeg.”

A March 23, 1946, editorial in the Free Press warned that more “energy and imagination” was needed to relieve the housing shortage in the city caused by a lack of building materials and labour.

“So serious is the shortage of materials and labor in the Canadian building supply trade that it is estimated that no more than about 1,200 dwelling units will be built in Winnipeg in 1946, which is no larger than the construction figure for 1945. This will include 400 dwellings of Wartime Housing still to be completed.”

The editorial claimed the shortage of materials and labour put in jeopardy the provision of low-cost housing to veterans.

One suggestion was to use materials — plumbing, electrical wiring, etc. — from military establishments no longer in use due to the end of the war.

Even in 1948, housing for veterans was labelled a disgrace by MLA Gordon M. Churchill. He said little progress was being made in the construction of low-rental and war-time housing, resulting in hundreds of veterans and their families continuing to live in overcrowded dwellings or emergency shelter huts (Free Press, March 1, 1948).

“I am not finding fault with the housing committee of the Winnipeg city council,” Churchill said. “That committee has done good work. I wish this (Manitoba) government had been a party to the plan. What I desire to see is assistance from this government to every municipal authority with a housing problem to solve.”

The lack of adequate housing in Winnipeg was revealed in a 1948 report by William Courage, the city’s general supervisor of emergency housing, which found that only 10 per cent of all the city’s housing had been built after 1930 with all the rest being built prior to that year. This was a natural outcome of the deprivations arising from the Great Depression and the sacrifices made on the homefront after six years of supporting the war effort.

Another report urging for the creation of a Greater Winnipeg (the city and surrounding municipalities, such as St. James, St. Vital, East Kildonan, St. Boniface, etc.) housing authority indicated that there were 46,733 dwelling units in Greater Winnipeg in 1937 and 53,726 by October 1948, but the doubling up of families in homes during the depression and a resulting surplus of housing caused few new dwellings to be built.

“Ending the war, a record number of marriages and prosperous times have all contributed to the present acute shortage,” according to the report.

Still, house construction continued at a feverish pace. Angus McClaskey, the supervisor of the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation (forerunner of today’s Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, or CMHC) for the prairie region, reported that house construction in Greater Winnipeg hit 3,487 “dwelling units” in 1947, while 2,345 units were built in 1946 (Free Press, January 13, 1948).

But that was just houses, rather than a big jump in low-cost rental units. According to the 1941 Canadian Census (two years into the Second World War), only 43.9 per cent of Winnipeggers were homeowners, which indicates that with the return of veterans added pressure was put on the rental housing supply.

(Next week: part 3)